JUDGE PRIEST (1934)

Something like John Ford’s 80th film, if IMDB can be trusted. Contemporary with L’Atalante and the silent Story of Floating Weeds. Set in 1890’s Kentucky – a couple decades past Civil War, which was still on everyone’s mind. And after all, the war wasn’t all that long ago… older audience members watching this film would’ve had parents who participated in it. Strange to think about now, a few more generations removed – my dad wasn’t born yet when this came out.

Humorist cowboy and populist philosopher Will Rogers plays the titular good-ol’-boy judge, and controversial sleepy-eyed black actor Stepin Fetchit is his sidekick. Priest is a former confederate soldier (“I kinda calmed down”) who is endlessly proud of Dixie, but respects the law and modern reality, or seems resigned to them anyway.

The judge’s nephew Jerome (Tom Brown) comes back to town and you can tell he’s supposed to end up with the neighbor girl Ellie May (Anita Louise) but he keeps ending up on dates with a dark-haired temptress instead (Rochelle Hudson, who voiced MGM cartoons and later appeared in Strait-Jacket and Dr. Terror’s Gallery of Horrors). Of course they do end up together after wasting plenty of screen time we’d rather be spending with Will Rogers, but first there’s some problem about Ellie May not having a father.

Our generic romantic leads… everything else in the film is more interesting than these two:

Trouble starts in town when the mysterious new guy in town, a blacksmith (the Walter Matthau-looking David Landau of Horse Feathers) punches out Flem the barber for making a crack about Ellie May. He is to be tried in court before Judge Priest, but meddling, villainous-looking senator Horace Maydew points out that Priest was present at the incident and took the blacksmith’s side, so Priest agrees to step down and let someone else (Henry Walthall, in the movies since 1908, costarred in Birth of a Nation and London After Midnight) preside. Priest stays involved by offering to defend the blacksmith, finally, triumphantly revealing him to be an ex-con, a confederate war hero, AND Ellie May’s father.

I found less stirring emotion in the overlong “dixie”-soundtracked heartfelt courtroom ending than in a scene early on with the judge talking to a photo of his dead wife. He’s supposed to be a lonely man, but with the young lovers and the big trial, and with Priest’s jovial nature, Ford doesn’t dwell on that aspect too much… just gives us that one lovely scene providing Priest with a deep enough soul to last the rest of the film.

Otherwise things stay pretty light, and there’s plenty of worthwhile diversions like the outrageous performance of Stepin Fetchit, and Hattie McDaniel (as Priest’s maid) singing “the sun shines bright in my old kentucky home.”

Look far-left for Hattie:

Screenplay written by Atlantan Lamar Trotti (American Guerrilla in the Philippines) and Dudley Nichols (Man Hunt, Scarlet Street). Based on a series of books by Irvin Cobb, author of McTeague (Greed), who hosted the Oscars the following year (1935 – this wasn’t nominated). Will Rogers had hosted in ’33. Time was unkind to the lead actors… Rogers, Walthall, and Landau all died within two years of the film’s release.

Sneering villain Horace Maydew:

–

THE SUN SHINES BRIGHT (1953)

I’d thought this would be a remake of Judge Priest, but not exactly. Sure, at the beginning a young man comes home and starts romancing a young girl with a conspicuously missing parent, and sure Judge Priest (now played by Charles Winninger, the captain in Show Boat) is our central character and Stepin Fetchit (the same actor!) is his slow, slurred-voiced sidekick/servant, but things take a turn from there.

Priest is still a likable soul, but now he’s an alcoholic on the verge of losing his seat to slick Horace Maydew. Priest doesn’t seem like he runs this hick town anymore – he’s an increasingly irrelevant member of a rapidly growing city. He’s a wise and engaging character, but he’s no Will Rogers. And while the first movie showed us the judge’s loneliness at the start then cheered us up for the next hour, this one gives the judge a rocky start (waking up and yelling for his negro servant to bring him whiskey!), builds him up more and more, then fires off a devastating visual ending, the judge silently retreating into his house alone.

Horace Maydew isn’t as cartoonish a bad guy in this movie:

The twist this time: young Lucy Lee’s mom, a prostitute who left town so her daughter wouldn’t grow up in shame, returns home to die. Lucy Lee finds out about this, and about her grandfather, the solitary wealthy General Fairfield (James Kirkwood, a director in the silent era, and the farmer in A Corner In Wheat), a former confederate who has distanced himself from his past and won’t talk before the veterans group which Priest leads each week.

The judge and the general share a tender moment:

Before LL’s mom died she asked brothel madam Mallie Cramp (Eve March: the little girl’s teacher in Curse of the Cat People, Hepburn’s secretary in Adam’s Rib) to give her a proper funeral and burial and strong-willed Mallie would like to, but she’s met with resistance by the townsfolk, who of course support the brothel but bristle at the idea of those women having public lives or even deaths.

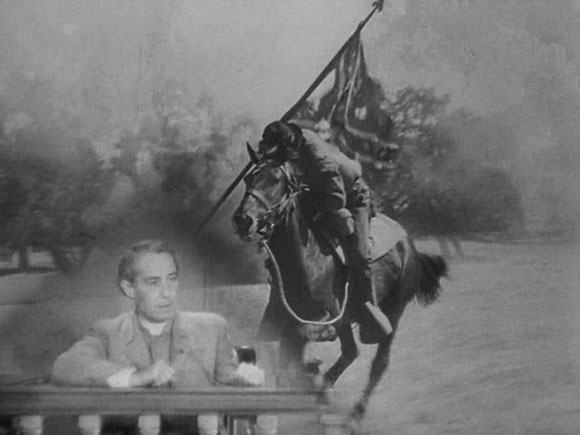

The rest of the plot is more complex than in Judge Priest. No big climactic court case, but a few overlapping issues. First, Priest is up for re-election and it’s a close race with Maydew (Milburn Stone, a detective in Pickup On South Street the same year), who paints Priest as old-fashioned and out-of-touch. Young lover Ashby (stiff, cliff-faced John Russell, the main bad dude in Rio Bravo) wins a whip-fight (!) with slimy rabble-rouser Buck Ramsey (Grant Withers, who killed himself a few years later) over Lucy Lee (Arleen Whelan of Young Mr. Lincoln), and Ramsey returns leading an angry mob hoping to lynch young black harmonica player U.S. Grant Woodford suspected of raping a girl out of town. Priest is already politicking around town, leading his confederate group, and dealing with the Lucy Lee situation when he decides to risk his life by blocking the lynch mob and risk his reputation by being the first to follow the prostitute funeral procession through the streets. Priest closes those matters out (U.S. Grant is proven innocent and released, actual rapist Buck is shot trying to escape, Lucy Lee reconnects with her grandfather) just in time to cast the decisive vote re-electing himself. In the end he’s a hero of the town, and everyone stops by his house to wave and sing praises… but he still goes home alone.

There were 30+ John Ford films between Judge Priest and this (including Rio Grande and The Quiet Man) and he had nearly 20 more left in him. This one, unlike the original, can definitely not be called a comedy. It has some comic relief though, in the form of drunken hick sharpshooter duo Francis Ford (his 32nd and final appearance in one of his brother’s films) and Slim Pickens (a decade before Dr. Strangelove and Major Dundee). I wanted to like the 30’s movie more, with its lighter tone and a Judge Priest character who is affable without having to humbly heal the whole town’s social wounds while saving a boy’s life, but I think the latter movie impressed me more deeply. No doubt they’re both excellent and make for a lovely double feature though.

Jonathan Rosenbaum:

Today The Sun Shines Bright is my favourite Ford film, and I suspect that part of what makes me love it as much as I do is that it’s the opposite of Gone with the Wind in almost every way, especially in relation to the power associated with stars and money. Although I’m also extremely fond of Judge Priest, a 1934 Ford film derived from some of the same Irvin S. Cobb stories, the fact that it has a big-time Hollywood star of the period, Will Rogers, is probably the greatest single difference, and even though I love both Rogers and his performance in Judge Priest, I love The Sun Shines Bright even more because of the greater intimacy and modesty of its own scale.

I should add that in between Judge Priest’s stopping of a lynching and his triumphant re-election brought about in part by the potential lynchers is the act that the Ford regards as his key act of moral and civil virtue – arguably far more important in certain ways, at least in this film’s terms, than his prevention of the lynching. I’m speaking, of course, of his joining a funeral procession for a fallen woman on election day, thereby fulfilling her dying request that she be given a proper burial in her own home town. Once Billy Priest joins this procession, he is followed by almost every other sympathetic member of the community, starting with the local bordello madam and her fellow prostitutes, and continuing with the commander of the Union veterans of the Civil War, the local blacksmith, the German-American who owns the department store, Amora Ratchitt (Jane Darwell), Lucy Lee, Ashby, Dr. Lake, and finally – after the procession arrives at its destination, a black church – General Fairfield, Lucy’s grandfather, who has up until now refused to recognised his daughter under any circumstances.

There are actually two protracted and highly ceremonial processions in the film, occurring quite close to one another – the funeral procession for Lucy Lee’s mother and the parade of tribute to Judge Priest – and the fact that these two remarkable sequences are allowed by Ford to take over the film as a whole is part of what’s so extraordinary about them. Retroactively one might even say that they almost blend together in our memory as a single procession – despite the fact that the first is an act of mourning and the second is an act of celebration – and this undoubtedly contributes to the feeling of pathos in the film in spite of its overdetermined happy ending.

Ultimately, what the film may be expressing is neither celebration nor lament, perhaps just simply affection for cantankerous individuals who exude a certain sweet pathos because history has somehow passed them by – as someone says in the film, I believe in reference to the Confederate veterans, ‘the doddering relics of a lost cause’, which also suggests The Southerner as Everyman. This implicitly suggests a certain darkness as well as lightness – which is why the local blacks serenade the judge with ‘My Old Kentucky Home,’ the first line of which is, ‘The Sun Shines Bright’ – and yet this is a film bathed mainly in the melancholy of twilight. For to emphasise and focus on lost causes as opposed to causes that still might be won assumes a certain abstention from politics associated with defeatism – one reason among others, perhaps, why the Civil War plays such a central role in American history as well as in Ford’s work.

Someone can tell me if I’m out of line in quoting too heavily from this, but it’s so nice to see long, well-thought article devoted to an obscure classic film. If only EVERY film had as thorough a write-up on these internets. Maybe some day.

Our generic romantic leads. Once again, everything in the film is more interesting than these two, but this time Ford seems to realize it.

Merian C. Cooper’s name is on the title card – first time I’ve seen him mentioned in a non-King Kong context. I guess he exec-produced a bunch of John Ford movies. Shot by Archie Stout, who won an oscar the previous year for Ford’s The Quiet Man.