The Joke (1969, Jaromil Jires)

The joke was a cynical line he wrote to a girl he liked in a piece of intercepted mail which got him sent to a tribunal and kicked out of college – I didn’t mean to program a monthly theme of getting kicked out of school along with Education and Downhill. The flashbacks are wonderful, nobody plays the lead character as a young man, the camera is his stand-in, and his memories overlap the present, so the words of his expulsion tribunal are dubbed into a church ceremony he’s wandered into.

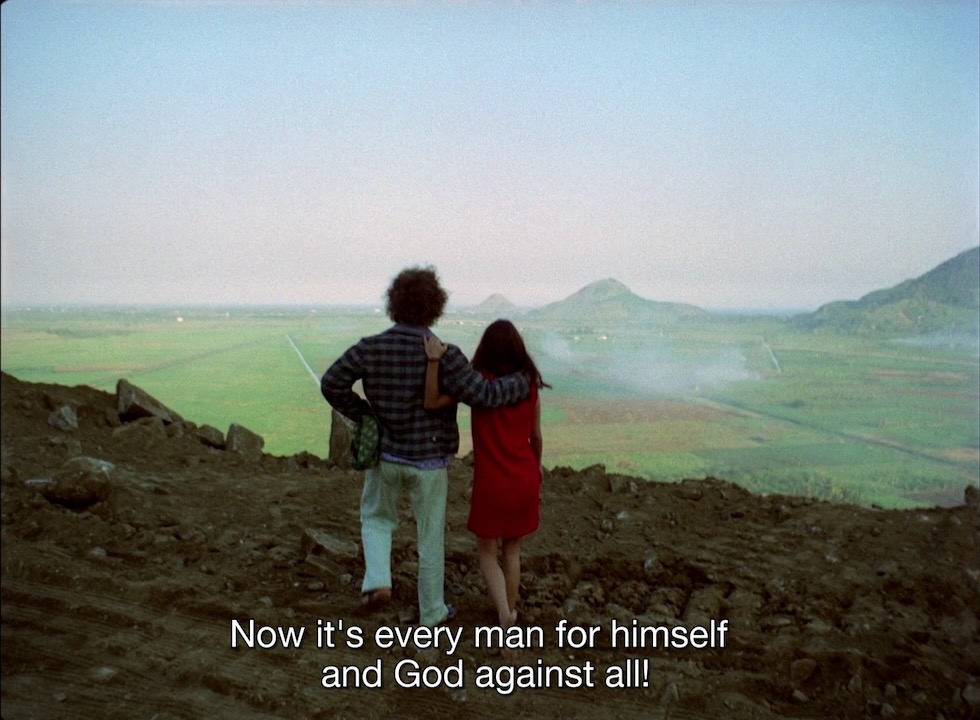

In present day our guy (Josef Somr of Morgiana) meets up with Helena (of the 1984 AI horror-comedy Grandmothers Recharge Well!) with a revenge scheme, meaning to seduce the wife of one of his accusers. All goes smoothly, except that the married couple are separated so the husband is happy that she’s found a new man, and Helena’s assistant is in love with her, and when our guy tries to ditch her she attempts suicide (Canby found this part “very funny”).

when your girl Marketa says she will stand by you:

when your revenge plot has fallen apart:

It was banned for decades, of course… based on a novel from the writer of The Unbearable Lightness of Being… Jires’s followup would be Valeria and Her WOW.

–

Zid / The Wall (1966, Ante Zaninovic)

Decent little animation with hot music. Man in bowler hat sits patiently by a giant wall, until aggrieved naked man comes along and tries everything in his power to get through it, finally headbutting it and himself to death. Bowler man walks calmly through the new hole and waits at the next wall.

–

The Fly (1967, Marks & Jutrisa)

Yugoslavian animation. Impassive guy tries to squish a fly but it escapes and doubles in size every quarter minute until it’s large enough to annihilate the man’s world and send him hurtling through space. Aware of their power over each other, they decide to be friends? Someone had fun with the all-buzzing sound design. Not to be confused with The Fly or The Fly.

–

Be Sure to Behave (1968, Peter Solan)

Girl in prison solitary washes up, pees, paces, watched always by an eye in the door. She imagines scenes suggested by crack patterns in the wall. Then she’s dressed up all nice, blindfolded, escorted to a park and released. She narrates all this too – unsubtitled, whoops, but it’s a soviet psychodrama of some kind. Czech, Vogel had the subtitles:

In this film a woman prisoner, harshly incarcerated, is suddenly released as unpredictably as she had been imprisoned; “Stalin is dead,” she is told, and then, significantly, “Be sure to behave.”

–

Jan 69 (1969, Stanislav Milota)

Czech funeral doc, aka Funeral of Jan Palach. Jan has died young, burning himself in protest of Soviet occupation, and the people are all turning out. Silent, set to doomy choir music.

–

Don Kihot (1961, Vlado Kristl)

Not what I was expecting given the title. Confusing flying machines, a cross between WWII planes and faces with bristly mustaches, bustle about. This tall robot must be the Don, taking on all the mustache pilots at once, going rogue in a police state. Big showdown arrives and the Don pauses to make out with a magazine, then either wins or loses, I couldn’t follow the abstract character design. Some pointedly handdrawn backgrounds (no straight lines) and inventive prop stuff. Unreleased in its native Yugoslavia, Vogel: “Don Quixote has become mechanized and is threatened by a technological society bent on destroying his individuality. He defeats it by exposing it to the power of art and poetry; but the art work is itself ironically distorted, raising a question mark.”

–

Among Men (1960, Wladyslaw Slesicki)

Stray dog draws the attention of some kids playing war and they attack it. It’s sold to a medical research place but escapes. Rounded up and leashed by animal control, rescued and taken to a friendly animal farm, but flees again, hungry on the streets. This city is portrayed as a shithole, with nice photography at least. This predates Balthazar and some other stories of innocent animals in a selfish human world. Vogel: “The most important of the famed Polish Black Series documentaries which dared to touch on negative aspects of socialist society.”