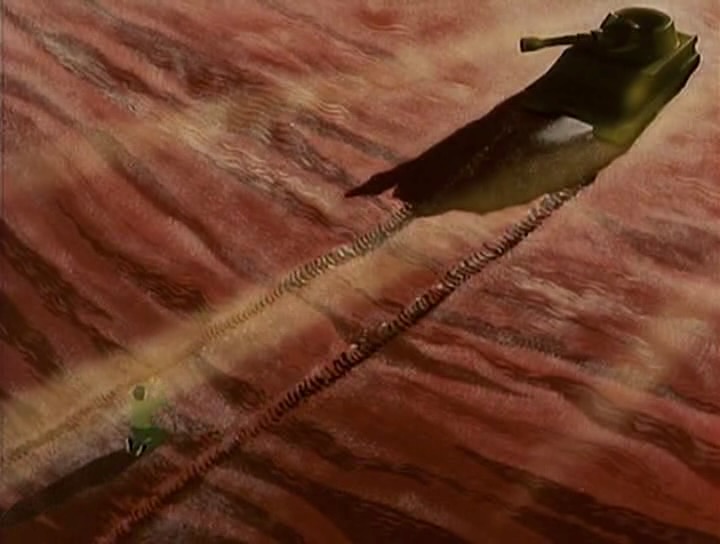

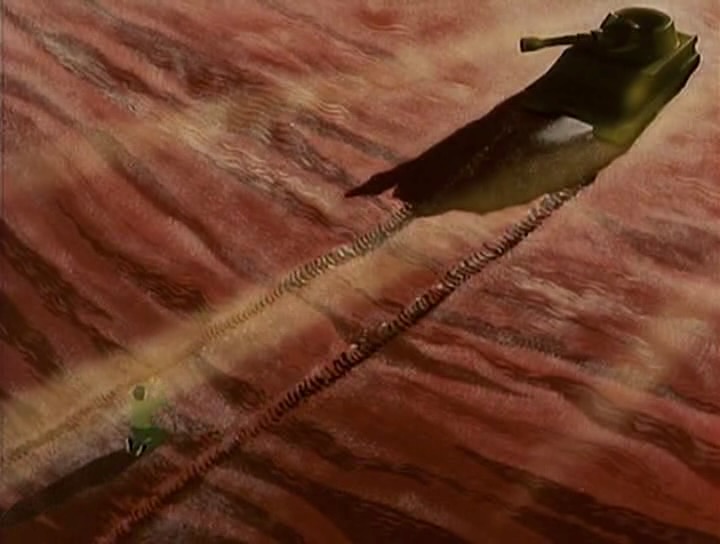

Firing Range aka Polygon (Anatoliy Petrov)

Professor’s son died in colonial wars, the prof invents an autonomous tank that can detect fear and sets it loose on his own army in revenge. Nice little sci-fi war drama, too bad about the grotesque rotoscoping. Not the Old Man and the Sea guy, this is a different Petrov, and okay it’s from 1977 not ’75, sometimes my dates are off.

–

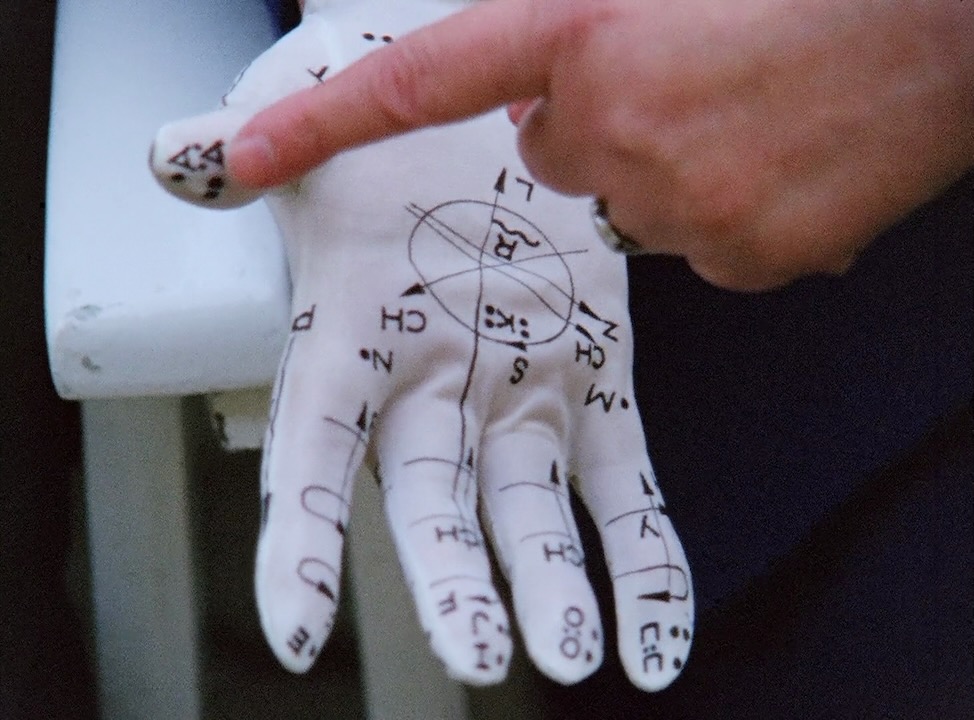

Great (Bob Godfrey)

Comic attack on the British empire, very good illustrations with Monty Python-style motion gives way to slightly more traditional animation full of newspaper-caricature characters, and settles into focus on Brunel, a builder of very large bridges and ships, with photographed segments and musical numbers. Not one of my favorite things, but I also believe there should be more farcical musical bio-pics of obscure historical figures. Won the oscar over Sisyphus and a Bafta over Caroline Leaf. A very naughty Brit, Bob is also known for Instant Sex and Kama Sutra Rides Again.

–

Perspectives (Georges Schwizgebel)

Roughly drawn figures keep changing form and direction over nice colored backgrounds and oppressive piano music.

–

Ventana (Claudio Caldini)

Thin rectangles flit past over some ambient music. Made me sleepy.

–

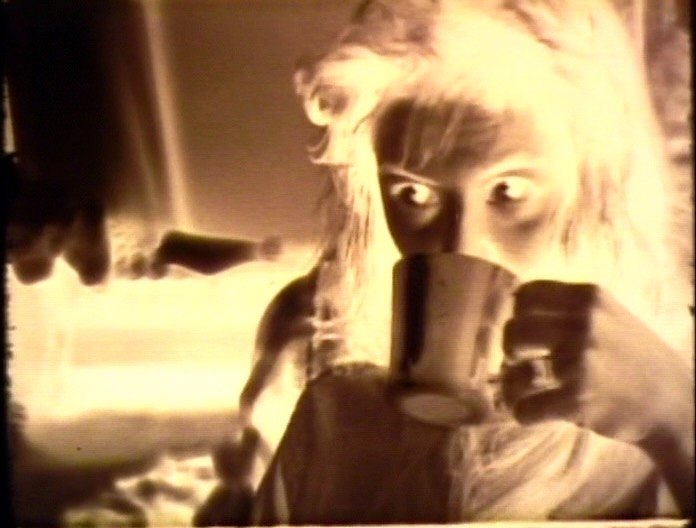

Sincerity II (Stan Brakhage)

Playing with the dog in the yard, playing with the wife in bed. I thought my copy was faded and orange with exposure problems, but sometimes you’ll get a clear, balanced shot or a strong blue-green, so who knows. Sincerity was Stan’s multi-part “autobiography” composed of footage shot by himself and friends. With ten minutes left we start seeing Stan himself, and the editing goes haywire. Naked children, a family train vacation, some trick photography play with the kids, a visit to Canyon Cinema. Silent; I listened to the latest Mary Halvorson album since her group is playing Roulette tonight.

–

The Seasons (Artavazd Peleshian)

Opens alarmingly with a man and a sheep going over a waterfall. Then the frame is taken over by clouds, then a mountain – maybe the title was mistranslated from The Elements. Cattle and sheep drive, men and horses getting a truck unstuck from rainy mud, a hay-sledding party, a sheep-sledding party. After all the hard work, everyone (even the sheep) get fancied up for the wedding of the man from the waterfall scene. No narration, but a couple of intertitles – postsync sound and nice orchestral score. Ah, this is Armenia, the title refers to the Vivaldi music, and it’s shot by The Color of Armenian Land director Vartanov.