Piecemeal protest doc with surprisingly great location footage and interesting scenes, each one a bit too loud and going on for too long. The pieces are mostly unsigned, but I believe Chris Marker put the project together, and some segments are either identified online, or just very easily guessed (ahem, Resnais). They mention that Joris Ivens shot on location – most everyone else stayed home and used stock footage or filmed protest marches.

“It is in Vietnam that the main question of our time arises: the right of the poor to establish societies based on something else than the interests of the rich.”

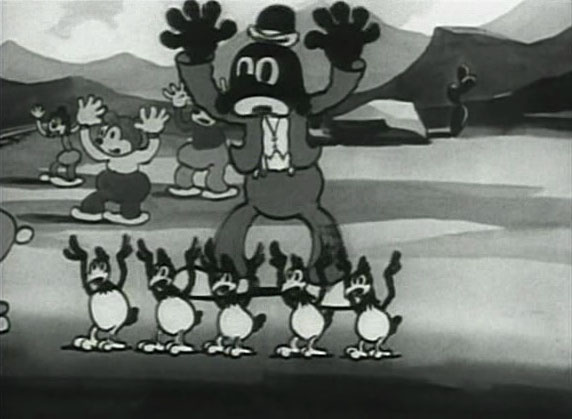

Cluster-bomb:

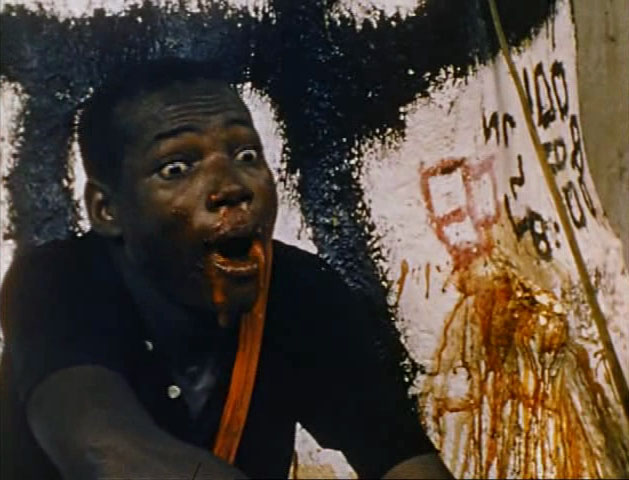

Supposed to be President Johnson:

The Resnais segment is interesting before it wears out its welcome. Bernard Fresson (of a few Resnais films, including a small part in Je t’aime, je t’aime) is playing “writer Claude Ridder” (name of the lead character in Je t’aime, je t’aime played by Claude Rich) while a woman Karen Blanguernon (Rene Clement’s The Deadly Trap) glares from the corner of his office. This segment was written by Jacques Sternberg (Je t’aime, je t’aime, of course), so perhaps Claude Ridder was his standard lead character name, since this Ridder seems too impassioned to be the heartbroken dead soul from the feature. “Ridder” monologues on the war, politics, and his own inability to make change. “A spineless French intellectual articulating excuses for his class’s political apathy,” per the NY Times.

Next, a history lesson using stock footage, photographs and comics, drawing connections to the Spanish Civil War (the Resnais had mentioned Algeria).

Then Godard, who monologues in front of a giant film camera, talking about the distance, his inability to connect with the war itself, or even the French working class, the focus of so many of his films. Since he can’t film on-location, he inserts Vietnam into his feature films. “I make films. That’s the best I can do for Vietnam. Instead of invading Vietnam with a kind of generosity that makes things unnatural, we let Vietnam invade us.”

After a jaunty music video to a protest song by Tom Paxton, a longer somber voiceover reading the words of Michele Ray who spent three weeks with the Viet Cong, showing her footage before it goes crazy at the end.

“Why We Fight,” in which General Westmoreland explains the official U.S. position on the war, filmed off a TV while someone zooms around and twiddles knobs. Title must be referencing the 1940’s U.S. propaganda film series Why We Fight, which Joris Ivens contributed to.

Anti-napalm rabbi:

Monologue by Fidel Castro, who gives his theories on guerrilla warfare and how this applies to Vietnam. The new wavers seemed to have easy access to Fidel back then.

Ann Uyen, a Vietnamese woman living in Paris discusses Norman Morrison’s setting himself on fire outside the pentagon, and what that meant to her people. “We think that in America there is another war, a people’s war against everything that’s unfair.” Then an interview with Norman’s widow, who seems in sync with Norman’s politics. This was by William Klein.

War protest zombie walk, probably shot by Klein:

Marker’s outro:

In facing this defiance [of the Vietnamese], the choice of rich society is easy: either this society must destroy everything resisting it – but the task may be bigger than its means of destruction – or it will have to transform itself completely – but maybe it’s too much for a society at the peak of its power. If it refuses that option, it will have to sacrifice its reassuring illusions, to accept this war between the poor and the rich as inevitable, and to lose it.