There’s a reason why this is the first Kurosawa movie on this site (and therefore the first I’ve watched in almost four years). After excitedly renting The Hidden Fortress, which I didn’t like, and Ikiru, which I did, I decided Akira was overrated and instead focused my attentions on Kiyoshi Kurosawa (no relation). Lately I’ve been greatly enjoying celebrated studio auteurs like John Ford, who make slow-paced movies without any spider-people, doppelgangers, magic trees, computer-virus apocalypses or killer jellyfish at all, so maybe it’s time to revisit A.K.

IMDB plot:

Murukami, a young homicide detective, has his pocket picked on a bus and loses his pistol. Frantic and ashamed, he dashes about trying to recover the weapon without success until taken under the wing of an older and wiser detective, Sato. Together they track the culprit.

A.K. follows his protagonist around the city, meeting shady characters in seedy parts of town, taking the camera out of the studio and bringing it along, influenced by the incompatible styles of film noir and neorealism. It’s a similar approach to The Naked City, and in a similar timeframe. I’d say Naked City was more successfully scenic, showed better city views, but Kurosawa did more with his less-than-stellar scenery. His mastery of camerawork, if not of pacing, shows up here.

At least the title character, the “stray dog”, is clearer than in The Thin Man – it’s Yusa, a small-time thief turned murderer with the help of detective Murakami’s pilfered pistol. The point is made again and again that Y. & M. came from similar backgrounds and befell similar fates until M. turned cop and Y. turned robber, leading to a climax of the two men fighting in the mud, dirty and interchangeable (not really, since Y. is wearing an unmistakable white suit by then). The other parallel is between M. as idealistic young cop with the weight of the world on his shoulders and elder cop Sato, with his burned-out black-and-white view of humanity. None of this is anything new by 2010 standards, but it may have seem fresh in ’49, and Kurosawa presents the ideas as if they’ve just occurred to him. By the end I couldn’t keep up my “ho-hum, Kurosawa” stance, was hooked by the style and story of the final third, featuring cross-cutting between Murakami’s bizarre interrogation of Yusa’s girl Harumi (with her mother in the room trying to help the cop) and Sato tracking down the killer in a hotel, as the oppressive heat of the last few days broke into a rainstorm.

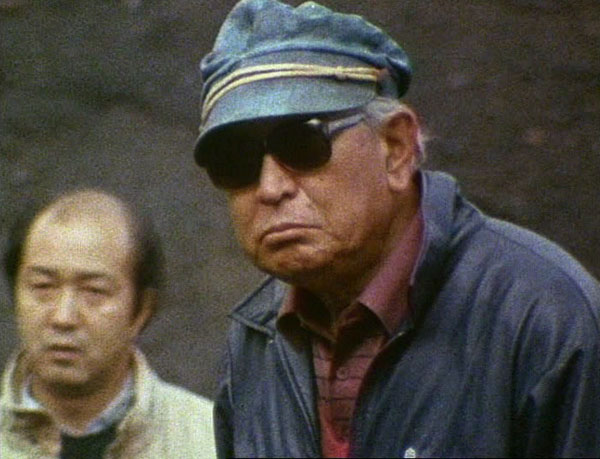

Thanks to Emory for showing this on 35mm, though it features the kind of harsh, blaring music that always sounds better softened by my TV or laptop speakers than it does cranked loudly in a theater. Only the 7th listed film with superstar Toshiro Mifune (Murakami). Elder cop Takashi Shimura, with his giant Edward G. Robinson lips, was in 200+ films from Mizoguchi’s 1936 Osaka Elegy to Kurosawa’s 1980 Kagemusha, with some Zatoichi and Godzilla films thrown in, plus Kwaidan, Life of Oharu, and the lead role in Ikiru. Stolen-gun-toting Yusa is Isao Kimura in his first film – he’d appear in a bunch of Kurosawa films, the Miyamoto Musashi trilogy, Naruse’s Summer Clouds and Fukusaku’s Black Lizard. Harumi, Keiko Awaji, was in When a Woman Ascends the Stairs, and her mother Eiko Miyoshi would play scores of mothers in Japanese films, finally a grandmother in Ozu’s Good Morning. Movie was remade in cinemascope in the 70’s with the stars of Tokyo Drifter and Red Angel. I tried to draw comparisons with the missing-police-gun stories in Magnolia and The Wire but could not manage to do so.

C. Fujiwara:

Through the constant unfurling of interposed surfaces (multiple superimposed images, the strips of mesh and garlands down which the camera cranes at the Wellesian Blue Bird club), Kurosawa evokes a world in perpetual motion.

The sequence in Stray Dog in which Murakami goes undercover in the streets of Tokyo to look for the gun lasts slightly over nine minutes—much longer than necessary to advance the plot and convey that his search goes on for some time. The feeling of excessive length comes from the lack, or the randomness, of variation: the viewer’s main impression is the ever-dawning awareness that the sequence has nothing new to give. Kurosawa’s intention is to heighten our identification with Murakami as he slogs through the lower depths. By immersing us in the world’s chaos so thoroughly, the director makes us rely all the more on Murakami’s obsession as a potential source of meaning and order, while at the same time showing how inadequate it is to pose the problem of this chaos in the specific terms of a missing gun.

T. Rafferty:

Murakami poses as a down-and-out veteran, which turns out to be an uncomfortably thin disguise: he is a veteran of the recent war, and as he wanders through the ravaged city, in an elaborate montage sequence, we sense that he’s experiencing a life he might have led—that these mean streets are, for him, a collective image of the road not taken. That sequence, which incorporates a fair amount of documentary footage shot by Kurosawa’s assistant Ishiro Honda (later famous as the director of Godzilla and Rodan), is much longer than it needs to be, but it’s the key passage in Stray Dog because it sets in motion the film’s real story: Murakami’s growing identification with the man who now possesses his gun.