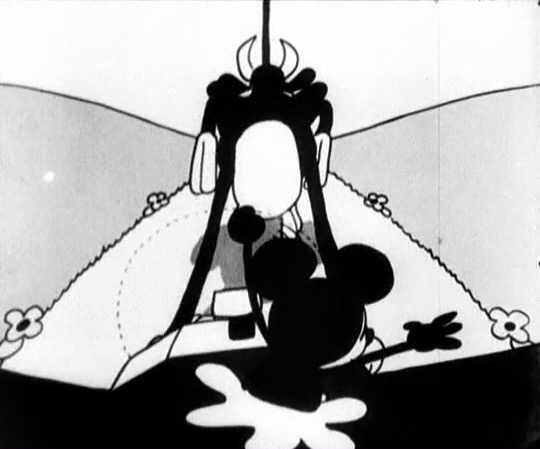

Cat Soup (2001, Tatsuo Sato)

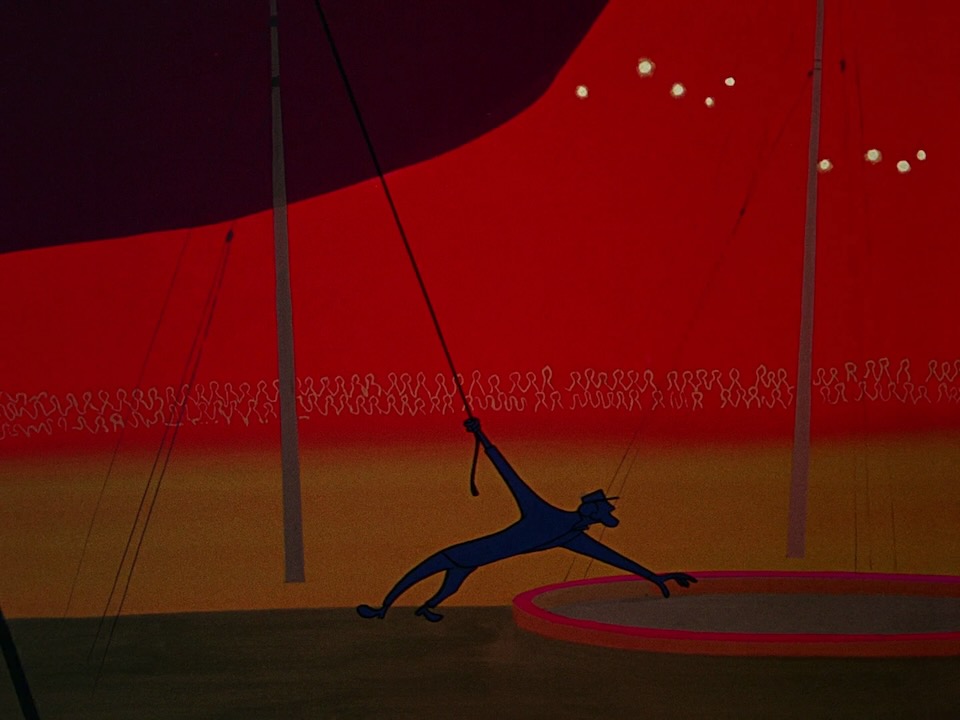

I don’t know Sato’s work, but I know animation producer Masaaki Yuasa, and this has got the wavy woozy quality of Yuasa’s features. A cat hits the town with his catatonic sister, whose soul was half-ripped by an evil shaman, and they experience all the major elements (desert, sea, time-freeze, soup) before landing back home. Incredible. One scene is set at the “Big Whale Circus,” making this part of the Werckmeister Harmonies universe. Sato is known for a series called Martian Successor, also did animated sequel series to both Ninja Scroll and Tokyo Tribe. There’s a separate Cat Soup series from the director of a Battle Angel Alita series.

–

Little Pancho Vanilla (1938, Frank Tashlin)

Kid claims he’s a bullfighter, gets catapulted into the arena, lands on the bull and is awarded first prize. Not top-tier Tash, it passed the time.

–

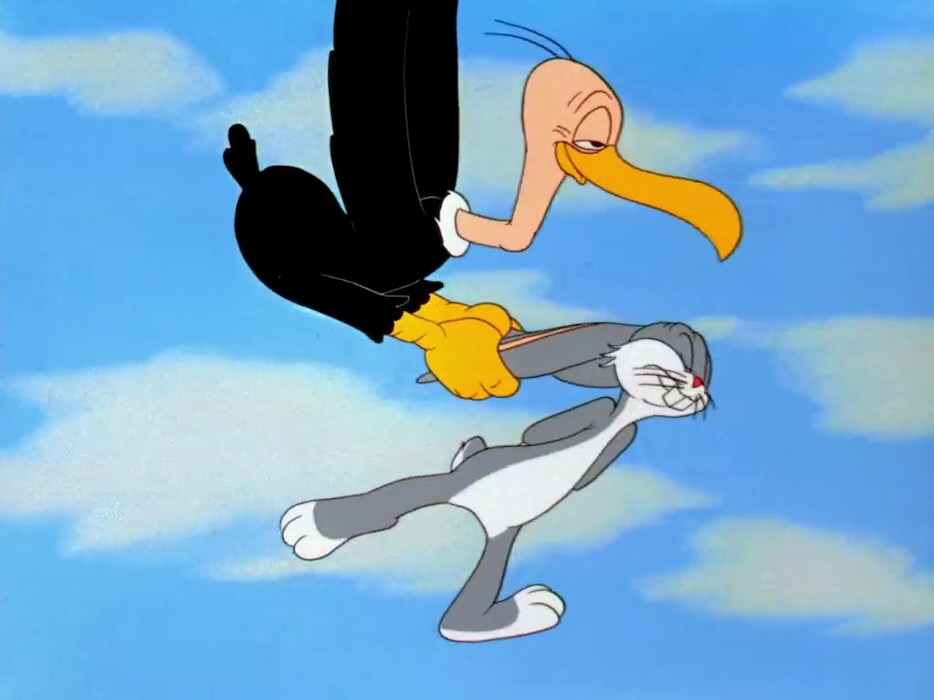

King-Size Canary (1947, Tex Avery)

Oh yeah, what if the cartoon had actual gags in it, wouldn’t that be better?

–

The Fantastic Flying Books of Mr. Morris Lessmore (2011)

After a major storm, books become birdies and Morris becomes a bookseller where reading turns the enchanted town residents from b/w to color. It’s all too precious for me, but wonderfully assembled – no surprise it won the oscar (over the Brave-era short La Luna). The directors are suspiciously named Brandon and William Joyce – also suspicious that each one co-directed a different 2014 11-minute Edgar Allen Poe short.

–

Seventh Master of the House (1966, Ivo Caprino)

Traveler asks a guy for a bed for the night, and gets sent to the guy’s father, and so on… then he gets the bed. It’s not much of a story, but it’s always good when our refined puppet animation devolves into increasingly bizarre characters until the final guy is shrunken to a quarter the height of his beard and resting in a horn hung on the wall. Some festival must’ve had a 12-minute minimum length so they added a framing story of a whitebeard man sitting in the snow writing this story (women do not exist in Norway).

–

Three Inventors (1980, Michel Ocelot)

2D doily-paper cutout stop-motion, oooh. Family of inventors keep creating wonderful things. The town “notables,” having no vision or creativity themselves, conclude that the inventors must be criminal philistines, and a mob burns their house down, destroying everything that is beautiful.

Mouseover to operate the magic lace pipe-organ sewing-machine:

Aftermath tells us it was only a movie:

–

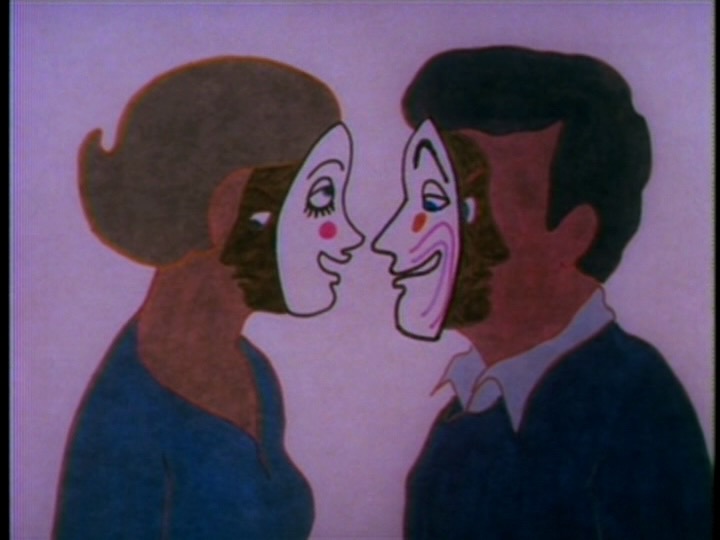

George and Rosemary (1987, Snowden & Fine)

Guy is obsessed with gal across the street, when he finally builds up the nerve to march over there he learns she’s been obsessed with him too. Oscar-nominated, but against two of the greats: Your Face and The Man Who Planted Trees.

–

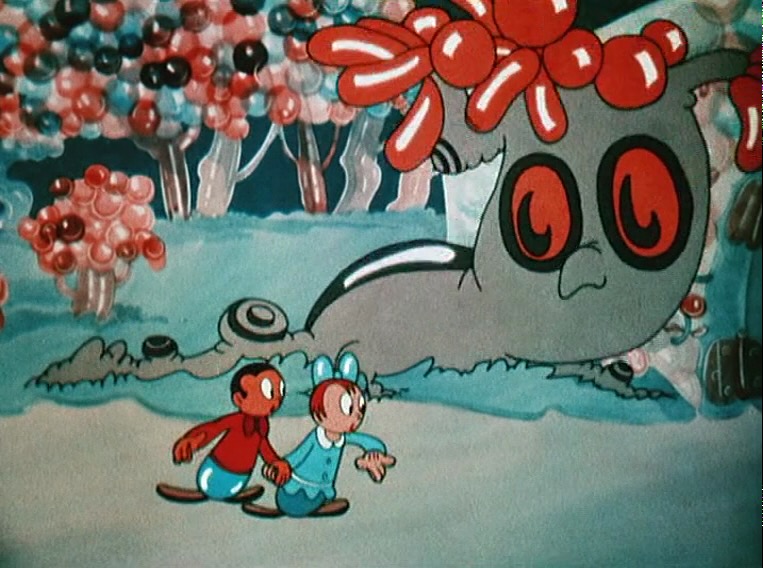

There Once Was a Dog (1982, Eduard Nazarov)

Guard dog is old and busted so he gets kicked out of the house, makes a deal with a wolf to get back into the family’s graces then repays the wolf with stolen food. Cute story and animation, and the would-be sentimental ending provided the biggest laugh of the night.

–

Glens Falls Sequence (1937, Douglass Crockwell)

The kind of paint-meets-clay blending that I love in The Wolf House. In standard-def I can’t even tell the difference between the 2D and 3D layers sometimes, or maybe it’s all 2D, but it’s wonderful. Feels freeform, making up new patterns according to whim, but returning to some (sexual/creature/religious) themes, like McLaren meets Bickford. I was gonna say the music is sometimes overwhelming, but I got caught up in the visuals and forgot that it’s a silent film and I’d hit play on Matmos A Chance to Cut.

–

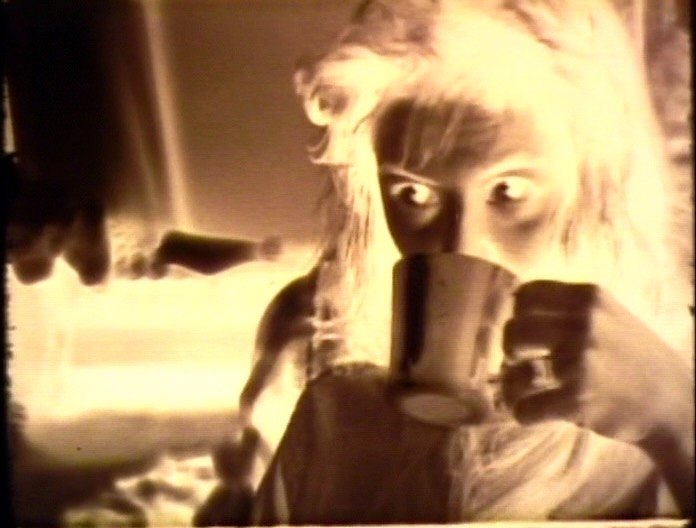

Simple Destiny Abstractions (1938, Douglass Crockwell)

A later film, but feels like the early demos that became Glens Falls. We’ll call it the bonus tracks. An advertisement painter, Doug made crazy motion experiments at his home in eastern New York state.

–

Mind the Steps! (1989, Istvan Orosz)

B/W Escher-sketch of a perspective-defying apartment building, sometimes telling little stories of residents or political oppression and sometimes just transforming things into other things. Scraps of warped sound effects and harmonica made me forget I wasn’t still playing the Matmos.

–

Syrinx (1966, Ryan Larkin)

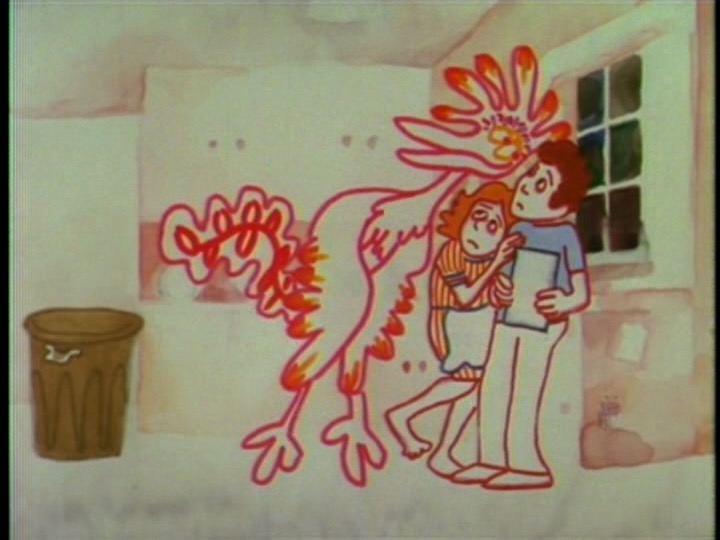

Sexy forest gods keep materializing then dissolving into abstraction. Music video for a flutey Debussy piece.

–

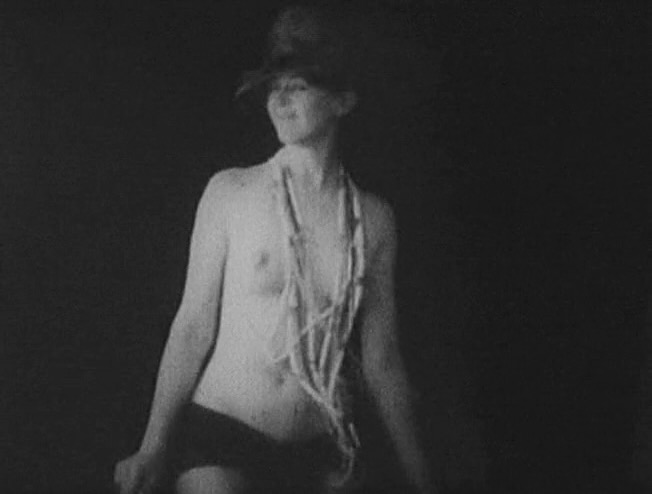

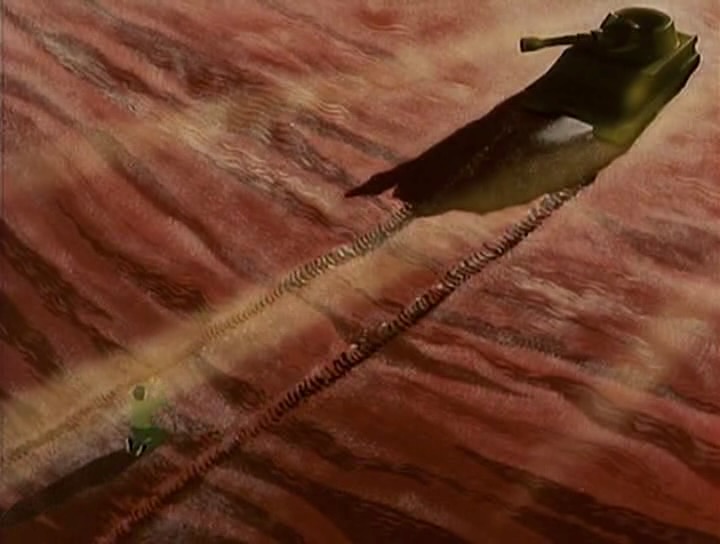

America is Waiting (1981, Bruce Conner)

Also a music video, for a good Byrne/Eno song. Not just a montage of fun stock footage, he warps the meaning of some shots by running them in forward and reverse. Lotta fun. I should’ve read that giant Conner book in the Ross library when I had the chance. At least there’s Screen Slate:

The success of [Mongoloid] led to an invitation from Brian Eno and David Byrne to make America is Waiting, a parody of paranoia that remains depressingly relevant. Using sourced material from the 1950s, he criticized reactionary politics, Western individualism, the Reagan administration, and military violence. When MTV rejected the video as part of their early programming that same year, it proved that corporate media always sanitizes rebellion.