Glass Life (2021, Sara Cwynar)

Photo-studio collage scroll with extreme digital compositing, music and voiceover tracks reinforcing or canceling each other, choice quotes from every modern philosopher, many objects and alphabets recognized from the gallery exhibit we saw, this 20-minute film itself refactored from a different exhibit. Daniel Gorman gets it.

–

Neighbours (1952, Norman McLaren)

Two guys get along until a sweet-smelling flower grows on their property line and they ultimately murder each other’s families and each other to gain possession of it. It’s bad politics, say both Alex and McLaren’s studio boss, but terrific live-action stop-motion, and the source of the Mr. Show knees-levitation effect.

–

Oz: The Tin Woodman’s Dream (1967, Harry Smith)

Smith loves transformative destruction, so the woodman whacks a tree with his ax, turning it into a pile of furniture and creatures, which eventually whirl around to form mystical fountain patterns. Psychedelic kaleidoscope setup starts with a Suspiria dance and leads to his most magickal images yet. Hoping to see this again next year with a live John Zorn performance, so instead of being obvious and playing Zorn with it now, I put on the middle third of Prefuse 73 One Word Extinguisher, which worked great during the dance scenes.

–

Ghosts Before Breakfast (1928, Hans Richter)

When Tom Regan said “Nothing more foolish than a man chasing his hat,” he had probably just watched this, a silly movie about flying hats and the men who chase them. Fun to see stop-motion with live actors 24 years before the McLaren short. My version has a new Sosin score since the original sound version was burned by nazis.

Lost hat:

Lost head:

–

Cosmic Ray (1962, Bruce Conner)

Nude dancing and fireworks set to a boogie-woogie Ray Charles song, after an excessive amount of countdown leader. It’s Conner, so there are quick shots of nationalism, Mickey Mouse, the atom bomb.

–

Walking (1968, Ryan Larkin)

More and less abstractly-rendered people and their walk cycles. Now that I’ve seen the Hubley short and the Disney doc about birds, that’s all the 1969 oscar nominees, and I’m gonna say they are all winners.

–

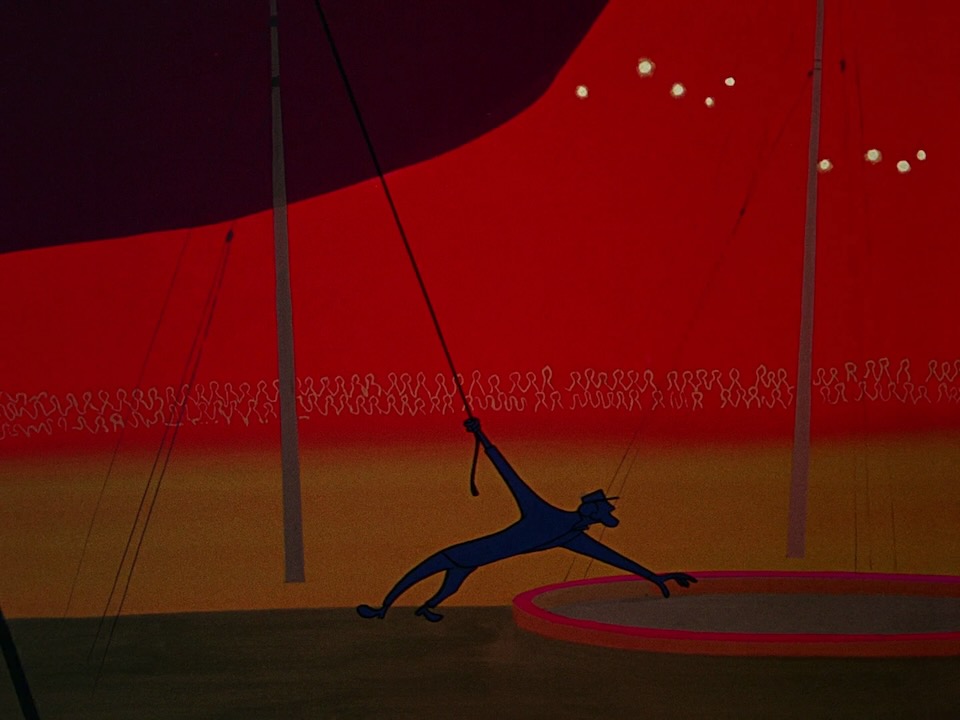

The Man on the Flying Trapeze (1954, Ted Parmelee)

Speaking of Hubley, here’s a UPA short. Talentless loser’s girl Fifi runs away with the circus to be with the handsome and graceful trapezeist Alonzo, turns out she’s a gold digger who leaves every man after they’ve showered her with gifts. Maybe the Popeye or W.C. Fields versions are better.

–

The Daughters of Fire (2023, Pedro Costa)

A Costa musical: after six minutes of split-screen, three women singing about their suffering, the last two minutes is landscapes. Paired at Cannes with Wang Bing’s Man in Black.

Continuing in the ever-darker visual trajectory of his previous films, in Daughters of Fire Costa pushes even further towards an obsidian palette … Over a string quartet rendition of 17th-century violinist and composer Biagio Marini’s Passacaglia (Op. 22), the three women, all professional singers, intone a hymn-like song whose lyrics speak of solitude and suffering, toil and exhaustion, and fortitude in the face of neglect. Given that the women are Black and singing in Creole, and that the themes they invoke are familiar from Costa’s films about Cape Verdean immigrants, it’s a surprise to learn from the end credits that the lyrics belong to a traditional Ukrainian lullaby.

–

Bleu Shut (1971, Robert Nelson)

Goofy prank film with structuralist tendencies – a no-stakes boat-name guessing game punctuated by half-minutes of weirdness (naked man in mirror chamber, dog gets Martin Arnolded, scenes from classic films, porn with intertitles). After minute three, a woman explains the rules of the movie and gives some coming attractions. I once saw about a third of this from one room away at an art gallery, maybe the same day we watched The Clock, and have wondered about it ever since.

It’s 19 minutes before either guy gets a single name right. The game show is abandoned towards the end for three minutes of people sticking their tongues out, then Nelson explains what the movie has been about, or he starts to before he’s interrupted by technical difficulties. Chuck Stephens did a Cinema Scope writeup, but I feel I’ve covered things pretty well.

–

The Garage (1920, Roscoe Arbuckle)

Our guys work at a garage, managing to get every thing and everyone covered in black oil without making any racist jokes, nice. The boss (a White Zombie witch doctor) has a cute daughter whose annoying beau manages to burn the place down, and it becomes a rescue operation. I got a good laugh from the ending of the Buster-has-no-pants segment.