The most I’ve laughed at an Anderson since Mr. Fox, maybe.

Jake

Back in theaters for this one. I love going into Wes movies with absurdly high expectations, because he always meets them. I’ll read the hater critics some other time – maybe they were looking for something more than an endless parade of favorite actors and impeccable production design, but I wasn’t. Much of the movie is in 4:3 black and white, and either my screening was over-matted or the titles appear at the extreme top and bottom of frame.

Bookending segments in the newspaper office, with editor Bill Murray alive in the first piece and dead in the second. Bicycle tour through the town of Ennui by Owen Wilson. Story 1 is relayed by Tilda Swinton, involving art dealer Adrien Brody patronizing imprisoned painter Benicio del Toro whose guard/model is Léa Seydoux (they get some actual French people in here sometime). I was least involved in the middle piece, about faux-May’68 student revolutionary Timothée Chalamet’s affair with reporter Frances McDormand. Then Jeffrey Wright is reporting on celebrated police chef Steve “Mike Yanagita” Park, who helps foil a plot by Edward Norton to kidnap chief Mathieu Amalric’s son.

Michael Sicinski (Patreon) also liked the Benicio story best:

By contrast, Anderson’s snotty riff on May ’68, “Revisions to a Manifesto,” succumbs to the director’s worst comedic instincts, essentially declaring that political desire is nothing more than sublimated horniness … The final segment, “The Private Dining Room of the Police Commissioner,” sort of splits the difference, although it is elevated considerably by a fine performance from Jeffrey Wright, channeling James Baldwin as a melancholy ex-pat uncomfortable with his journalistic distance. The story itself is mostly just a riff on The Grand Budapest Hotel‘s portrait of courtly civility as a bulwark against anarchy. But it’s Wright’s representation of honest inquiry, and humanistic curiosity, that makes it far less silly than it should be.

Watched again a month later, with Katy this time.

A few guys get a job to camp out menacingly in a family man’s house until he retrieves some documents from his workplace, but the documents aren’t so easily retrieved, and somebody dies, and who’s really working for who? It’s that sort of movie, and I could do a whole plot rundown but it’s twisty and fun so I’d rather just forget the particulars and watch it again in a few years. I’ll say that everyone’s sleeping around, all the women are dangerous, the documents are about the auto industry wanting to avoid pollution regulation, and Soderbergh shoots the action with a widescreen lens that perversely distorts everything on the sides.

Besides the superstars, we’ve got family man David Harbour (star of the Hellboy remake which I accidentally bought on blu-ray for a few bucks thinking it was the original, dammit)… his wife, hostage Amy Seimetz (director of last year’s finest film)… and Ray Liotta’s wife is Julia Fox (Uncut Gems).

Not how you want to meet Don Cheadle:

You do not impress Bill Duke:

You don’t want Brendan Fraser pointing his napkin at you:

Of our original trio, Han Solo has died in part 7, Leia now leads the resistance with second-in-command Laura Dern and Han-like hotshot flyboy Poe (Oscar Isaac), and Luke is secluded on an island refusing to help would-be protege Rey (Daisy Ridley) because he lost control of his last protege Kylo Ren (Adam Driver). John Boyega (Attack the Block) apparently had a larger role jumpstarting the narrative in part 7 – here he’s paired with engineer/love interest Rose (Kelly Tran) trying to help the rickety remains of the resistance escape from Kylo and howling ham sandwich Domhnall Gleeson in their attack fleet. Benicio Del Toro is a smooth traitor to both sides, there are computer-animated characters who don’t quite work, appearances by Yoda, Chewbacca and the robots. I appreciated Rian Johnson’s commitment to filming it all in well-designed visual frames, and this would probably rival the Guardians of the Galaxy movies in rewatchability, but that doesn’t make me happy that Rian is committed to a decade of Star Wars instead of original stories.

After this and Edge of Tomorrow, Emily Blunt is an action star. Though she was no hero in this one – she’d talk big, but ultimately she’s being used by compromised higher-ups who have no interest in her stupid morals. Josh Brolin is a boss, working with Benicio Del Toro, who turns out to be consolidating cartel power, I think, and/or taking personal revenge, by going all James Bond and assassinating some Mexicans at the end. Blunt and partner Daniel Kaluuya (star of my favorite Black Mirror episode) are forced along for the ride.

Think I like this Villeneuve fella. Storytelling is bizarre (probably plays better the second time around) with some groany dialogue and troop behavior but filming is nice. People said it was tense and scary but I still think El Sicario Room 164 is scarier.

M. D’Angelo:

Kate is incredibly strong in a situation where her strength is useless. This is a deeply pessimistic film about the near-impossibility of overcoming institutional corruption — one that’s honest enough to have its protagonist struggle for a long time about whether what she’s witnessing even is corruption.

It feels, accurately, like an adaptation of a long, wordy book, in that it’s a long, wordy movie that crams in characters and investigations and descriptions and dialogues and backstories through its runtime, leaving little breathing room or sense that it’s all adding up to something. And it feels like one of those sprawling PT Anderson ensemble dramas, in that it’s packed to the gills with great actors, some of them never better than here. And it’s faithful to the madcap trailer, in that it contains those lines and comic scenes. And it’s similar to Big Lebowski, in that they’re both quizzically-plotted red-herring comedies featuring addled detectives. But it’s like none of these things, the visuals closer to Anderson’s The Master than I was prepared for, the mood less comic and hopeful. Some of the critic reactions I looked up mention the dark, disillusioned second half of Fear & Loathing in Las Vegas, a good point of reference. It’s being called the first Pynchon adaptation, but only because nobody (myself included) saw the semi-official Gravity’s Rainbow movies Impolex and Prufstand VII. Random movie references, presumably from the book: a company called Vorhees Kruger, a street called Gummo Marx Way.

This is Joaquin Phoenix’s show, but his cop frenemy Josh Brolin keeps trying to kick his ass and steal it. Also great: Jena Malone as an ex-junkie looking for her husband, Katherine Waterston as Doc’s ex-and-future girlfriend with questionable allegiances, and Martin Short as a depraved dentist. Plus: Martin Donovan, Omar, Eric Roberts, Jonah from Veep, Reese Witherspoon, Owen Wilson, Benicio Del Toro, Maya Rudolph, Hong Chau and Joanna Newsom.

D. Ehrlich:

Anderson has imbued [Joanna Newsom] with a spectral dimension – every conversation she has with Doc sheds light on his isolation, but each of her appearances ends with a cut or camera move that suggests that she was never there, that she isn’t an antidote to his loneliness so much as its most lucid projection.

MZ Seitz, who is “about 90 percent certain [Newsom] is not a figment of anyone’s imagination.”:

Phrases like “peak of his powers” seem contrary to the spirit of the thing. Vice impresses by seeming uninterested in impressing us. Anderson shoots moments as plainly as possible, staging whole scenes in unobtrusive long takes or tight closeups, letting faces, voices and subtle lighting touches do work that fifteen years ago he might’ve tried to accomplish with a virtuoso tracking shot that ended with the camera tilting or whirling or diving into a swimming pool.

G. Kenny:

The movie walks a very particular high wire, soaking in a series of madcap-surreal hijinks in an ambling, agreeable fashion to such an extent that even viewers resistant to demanding “what’s the point” might think “what’s the point.”

D. Edelstein:

It’s actually less coherent than Pynchon, no small feat. It’s not shallow, though. Underneath the surface is a vision of the counterculture fading into the past, at the mercy of the police state and the encroachment of capitalism. But I’m not sure the whole thing jells.

Seitz again:

Something in the way Phoenix regards Brolin … suggest an addled yet fathomless empathy. They get each other. In its way, the relationship between the stoner “detective” who pretends to be a master crime fighter and the meathead cop who sometimes moonlights as an extra on Dragnet is the film’s real great love story, an accidental metaphor for the liberal/conservative, dungarees/suits, blue state/red state divide that’s defined U.S. politics since the Civil War.

A. O’Hehir:

Like Anderson’s other films (and like Pynchon’s other books), Inherent Vice is a quest to find what can’t be found: That moment, somewhere in the past, when the entire American project went off the rails, when the optimism and idealism – of 1783, or 1948, or 1967 – became polluted by darker impulses. As Pynchon’s title suggests, the quest is futile because the American flaw, or the flaw in human nature, was baked in from the beginning.

It’s like all the humorous bickering of The Avengers mixed with the action of… The Avengers. So it’s like The Avengers, or maybe Firefly. But funnier, and with more rock songs. Katy and I don’t like the shot-too-close, over-edited action scenes, but otherwise had no complaints.

Heroes: Andy Dwyer, hulky Dave Bautista (Brass Body in Man With The Iron Fists), green Zoe Saldana (Avatar), talking raccoon Bradley Cooper (Midnight Meat Train) and kinda-talking tree Vin Diesel (The Iron Giant). Not heroes: Andy’s mercenary ex-partner Michael Rooker, Zoe’s evil-blue-robot sister Nebula, “the collector” Benicio Del Toro, super baddie Ronan (partnered with Thanos, a main Thor/Avengers baddie) and Ronan’s enforcer Djimon “Digital Monsters” Hounsou.

Supplementary good guys: president Glenn Close and cops John C Reilly and Peter Serafinowicz.

Introduced: something called “infinity stones” which I think power some of the other magic stuff in Avengers-world, and rumored superhuman backstory for Andy.

An absolute monster of a movie. No longer called The Argentine and Guerrilla, it’s been simplified to Che part 1 and Che part 2 then run together into a “roadshow” with a 15-min intermission, a printed program, and no trailers, credits or titles.

Part one has flashbacks (or flashforwards, depending on your point of view) to Guevara speaking at the U.N., epic movie music, and titles telling us when and where (within Cuba) the action is taking place. Emphasis on Che’s medical skills and on all facets of the revolutionary struggle: weapons training, psychology and ideology, strategy and inter-group politics. Far as we can tell, it’s Fidel Castro who is leading the men, and Che is going where he’s told – though he gets the final glory of capturing the capital himself (against orders, which were to wait a couple days for the main group to arrive).

Part two: no flashbacks, no narrator, less obvious music, and titles simply number the days since Che’s arrival in Bolivia. Starts out a crafty spy tale, with Che in a master disguise to get into the country with everybody looking for him, then meeting the countrymen who yearn for revolution and think the time is right. Alas, the time is not right… the highly organized military government tracks the men, bombs their camps with help from the U.S., and most damning of all, turns the local citizens against the revolutionaries.

Part one is too much of a hero-portrait with too much of a classic film-history-reenactment trajectory, but part two is too dark, too gritty and hopeless with not enough signposts for the audience. The combination could’ve made for two so-so movies, but it doesn’t – not at all – instead, the weaknesses of each disappear in the presence of the other, forming one extremely strong work, probably Soderbergh’s best.

From the writer of Eragon and Jurassic Park III… I’m serious! Besides Cannes-winner Del Toro and hundreds of unfamiliar faces, we had Catalina Moreno (of Fast Food Nation, Maria Full of Grace), Gaston Pauls (star of Nine Queens), Lou Diamond Phillips (who I didn’t recognize; only place I’ve seen him in 20 years is Bats), Jsu Garcia (Traffic, Nightmare on Elm Street) and a cameo by Matt Damon.

When bad American drug guys feed 007’s friend to big fish, there will be many fish-related revenge killings! But when Bond is fired by the British government for going vigilante, he goes… well, even more vigilante to continue the revenge stuff. Movie soon turns less aquatic, with more dirty, dusty drugs-and-oil-type crime going down. This is the movie where Bond drives a tanker truck up on half its wheels to avoid a missile blast, which is only slightly less laughable than the rocket vs. handcart scene in Darkman III: Die Darkman Die, but looks cooler.

From John Glen (the director of a Christopher Columbus movie with Tom Selleck) and the writer of The Great Gatsby (according to IMDB, anyway). Timothy Dalton of Hot Fuzz is Bond. Movie seemed long; was long.

Must’ve been sponsored by velcro – the stuff pops up everywhere.

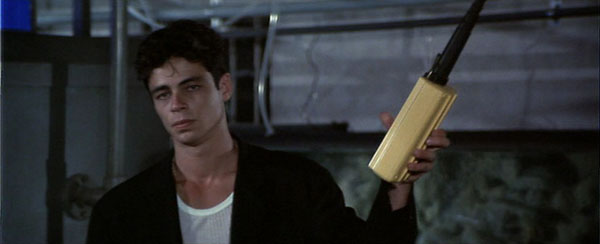

Most importantly, Benicio Del Toro:

Benicio Del Toro!

Benicio Del Toro: