“Why sometimes do images begin to tremble?”

From the film:

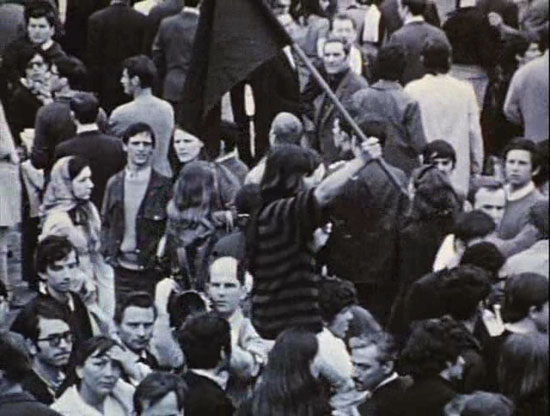

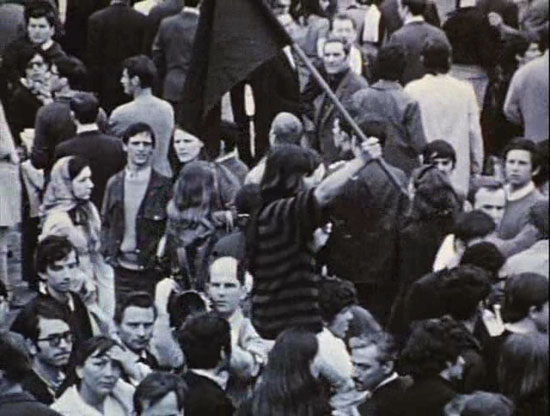

1967 saw the arrival of a rather peculiar breed of adolescents. They all looked alike. They would immediately recognize each other. They seemed to posses a silent but absolute knowledge of certain issues but to be totally ignorant about others. Their hands were unbelievable skillful at pasting up posters, handing paving stones, spraying on walls short and cryptic messages which stuck in the memory, all the while calling for more hands to pass on the message they’d received but had not completely deciphered. Those fragile hands have left us the mark of their fragility. Once they even wrote it on a banner. “The workers will take the flag of struggle from the fragile hands of the students.” But that was the following year.

Watched the 3-hour 2008 edit with English narration. There are so many versions of this out there… maybe next time I can watch the 2008 or 1977 French with subtitles.

I thought I’d have more to say about it… three hours’ worth of Chris Marker’s most celebrated film, but I don’t really. Marker is mainly credited as an editor here, arranging others’ footage to show a bigger picture. There’s no wall-to-wall narration, just pops up occasionally. And I’m starting to notice a real sadness beneath many of Marker’s films… the same feeling in Chats Perches is present here. Glad I prepped a little by watching Sixth Side of the Pentagon and Battle of Chile, but I still had to check on wikipedia to see what exactly happened in Bolivia (Che Guevara killed Oct. 1967) and Prague (Jan-Aug 1968, attempted reform of Czech socialism led to 30 years of Soviet military occupation). The movie isn’t here to teach basic history of revolution – assumes you know something already, and since I quit reading The People’s History of the United States before it reached the 1900’s, I do not. Still, was able to follow the movie, thought lots of the footage was excellent, enjoyed watching and learned a little. Some segments have little gems of Marker wit in their editing or narration, but much of it is making connections between different scenes of revolution, both real and wishful, and thinking about what has been achieved, what might have been achieved. Really have to watch again sometime.

Either this was an early use of the electronic soundtracks that Marker would use in Sans Soleil and beyond, or the sound on my copy of the movie was pretty badly distorted. Or, more likely, both. The sound got worse during part two – there were some sections when I couldn’t make out any of the (English) dialogue.

Video and audio footage by: Pierre Lhomme (Mother and the Whore, Le Joli Mai, Army of Shadows), Etienne Becker (The Spiral, Le Joli Mai, Malle’s Calcutta), Michele Ray (Latcho Drom), Francois Reichenbach and his crew, Harald & Harrick Maury (The Owl’s Legacy, Day For Night, In the Year of the Pig), Théo Robichet (Band of Outsiders), Pierre Dupouey (Silence… on tourne), Raymond Adam (Jodorowsky’s Tusk), Paul Bourron of the Dziga Vertov Group, Willy Kurant (Far From Vietnam, Masculin-Feminin, Pootie Tang), Peter Kassovitz (Jakob the Liar), Paul Seban (Welles’s The Trial), Michel Fano (Rivette’s The Nun), Fernand Moskovitz (Last Tango in Paris), Yann Le Masson (Je t’aime moi non plus), Mario Marret & Carlos de los Llanos (À bientôt, j’espère), Jimmy Glasberg (Sans Soleil, Shoah), Robert Dianoux (Africa, I Will Fleece You), Jean Boffety (Thieves Like Us, Je t’aime je t’aime, Adieu Philippine), Robert Destanque (Joris Ivens’s The Threatening Sky), Hiroko Govaers (Terayama’s Fruits of Passion), Michel Cenet (Celine and Julie Go Boating), and an excerpt from Volker Schlöndorff’s The Lost Honor of Katharina Blum. That is quite a list of collaborators, though you never hear anyone talking about them.

English voices: Jim Broadbent (Brazil), Cyril Cusack (Fahrenheit 451), Robert Kramer (dir. Ice, Against Oblivion), Alfred Lynch (The Hill), and numerous British 1970’s TV actors.

“You can never tell what you might be filming.”

Quotes and other reactions:

Icarus Films calls it an “epic film-essay on the worldwide political wars of the 60’s and 70’s: Vietnam, Bolivia, May ’68, Prague, Chile, and the fate of the New Left.”

J. Hoberman: “Marker begins by evoking Battleship Potemkin, and although hardly agitprop, A Grin Without a Cat is in that tradition—a montage film with a mass hero. Unlike Eisenstein, however, Marker isn’t out to invent historical truth so much as to look for it. (The untranslatable French title, Le Fond de l’air est rouge, is a play on words suggesting that revolution was in the air but not on the ground.)”

Paul Arthur: “In its rhythms and editing structures, Grin tries to embody the very shape and textures of historical transformation, rendering the abstraction of change as an amalgam of rapid, plurivocal, uneven, and, at times, contradictory forces aligned in provisional symmetries encompassing past, present and future perspectives.”

Y. Meranda: “The editing de-emphasizes the narrative structure and instead stresses the poetical interrelationships of the sequences by putting almost all of them out-of-context. … Paralleling the visual editing, the sound editing is more based on poetical considerations than on intellectual ones. … Because there is very little attention paid to the intellectual arguments and because the style goes beyond making statements about a political ideology, A Grin Without a Cat becomes much more than a left wing documentary about the left: It achieves to be a poem about revolting against the system (and not just the political system), the conformity and the order. It suggests that it is an eternal struggle that is supposed to fail (as was in the case of the New Left) most of the times. This universality, achieved by Marker’s distinctive style, is what makes the film great.”

Excerpts from the Lupton book:

“Marker explicitly pitched the film against what he saw as the historical amnesia surrounding the period promoted by its treatment on television, where ‘one event is swept away by another, living ideals are replaced by cold facts, and it all finally descends into collective oblivion.'”

Movie is partially composed of outtakes from other projects. “Introducing the published script, Marker wrote that he had become curious about all the material that had been left out of militant films in order to obtain an idealogically ‘correct’ image, and now wondered if these abandoned fragments might not yield up the essential matter of history better than the completed films.”

“As a groundbreaking work of visual historiography, Le Fond attempts nothing less than to give cinematic form to the chaotic and contradictory movement of world history during the tumultuous decade that it covers.”

“The reappearance of cats, even in this thoroughly politicized context, is a signal that Chris Marker was beginning to re-emerge from the anonymity of unsigned militant productions and to reintroduce into his work the familiar tokens of his own distinct presence.”

Chris Marker:

Scenes of the third World War 1967-1977

Some think the third World War will be set off by a nuclear missile. For me, that’s the way it will end. In the meantime, the figures of an intricate game are developing, a game whose de-coding will give historians of the future – if they are still around – a very hard time.

A weird game. Its rules change as the match evolves. To start with, the super powers’ rivalry transforms itself not only into a Holy Alliance of the Rich against the Poor, but also into a selective co-elimination of Revolutionary Vanguards, wherever bombs would endanger sources of raw materials. As well as into the manipulation of these vanguards to pursue goals that are not their own.

During the last ten years, some groups of forces (often more instinctive than organized) have been trying to play the game themselves – even if they knocked over the pieces. Wherever they tried, they failed. Nevertheless, it’s been their being that has the most profoundly transformed politics in our time. This film intends to show some of the steps of this transformation.

More images:

The Chairman:

Funeral in Prague:

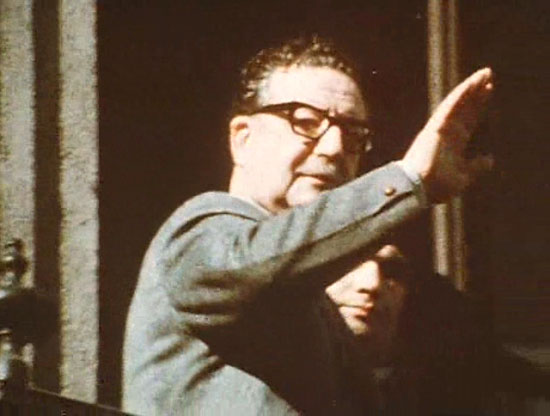

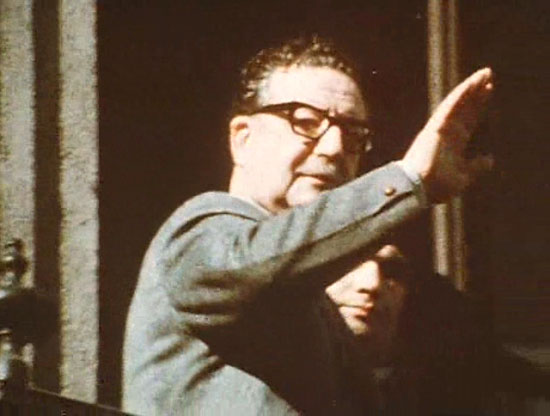

Last footage ever shot of Salvador Allende:

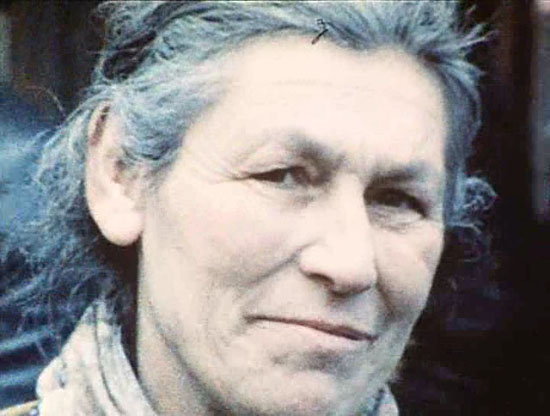

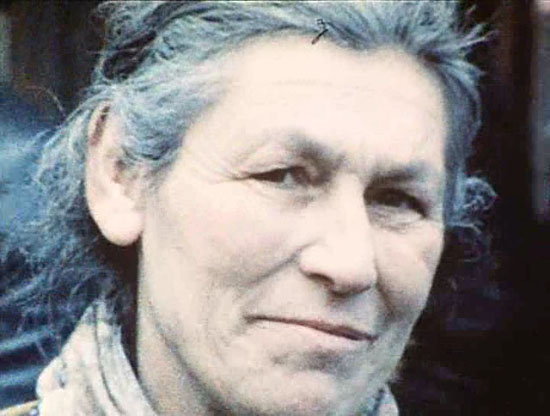

Allende’s daughter, who would commit suicide in 1977:

Fidel in Russia:

Enormous cats (no owls):

Nixon looks on: