Another freewheeling Rivette film, with its 16mm look and protagonists running throughout the city of Paris in the midst of a game with ill-defined rules, seeking to unveil a conspiracy, like a scaled-down Out 1.

Two girls meet on the street, run around a Paris that seems to be populated only by themselves and various conspirators, and get caught in a game, possibly of their own making. There’s more energized music than usual for Rivette, with drums and accordion and strings. Whirling camera, 360-degree pans, many shots of local monuments also recall Out 1, specifically its final shot. But this film has a lighter touch, also bringing to mind Celine & Julie Go Boating, with its playfulness and our heroines’ mysterious bond to each other. The dialogue is a bit new-age, the actions are somewhat improv-theater, it seems to have been shot entirely in real locations, and perhaps in a hurry, since I caught the boom mic a few times.

Films in the film:

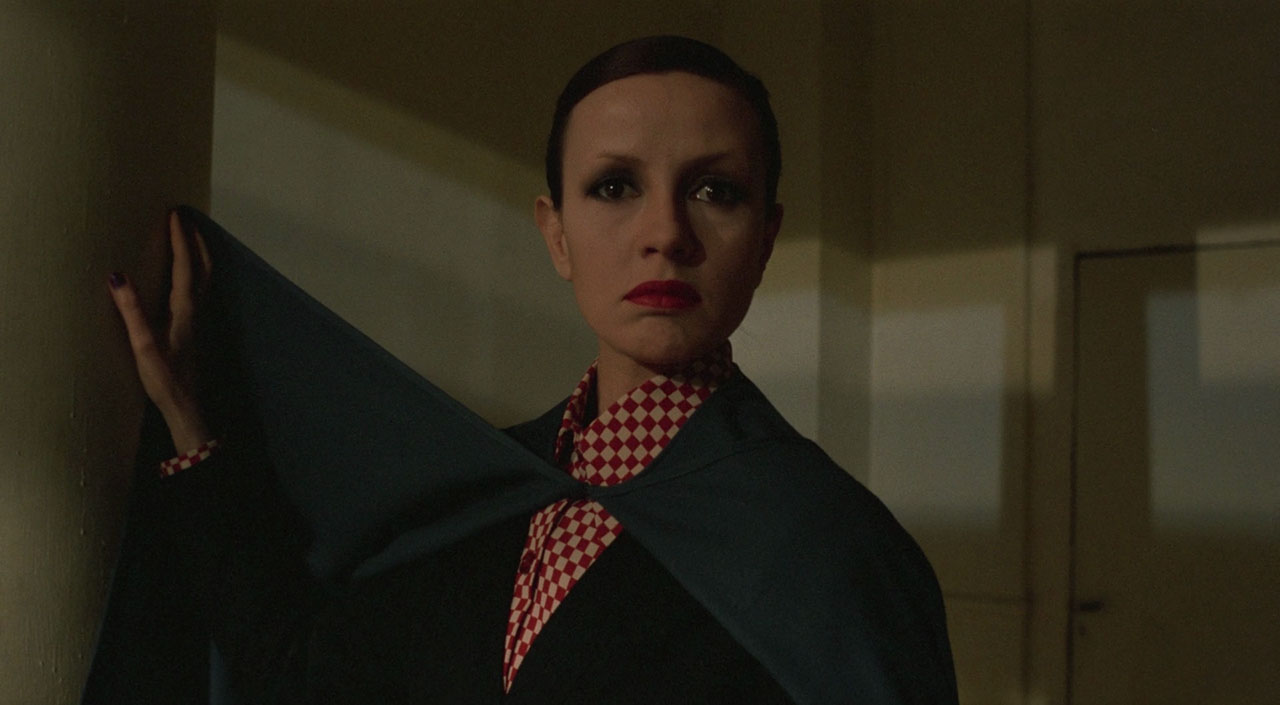

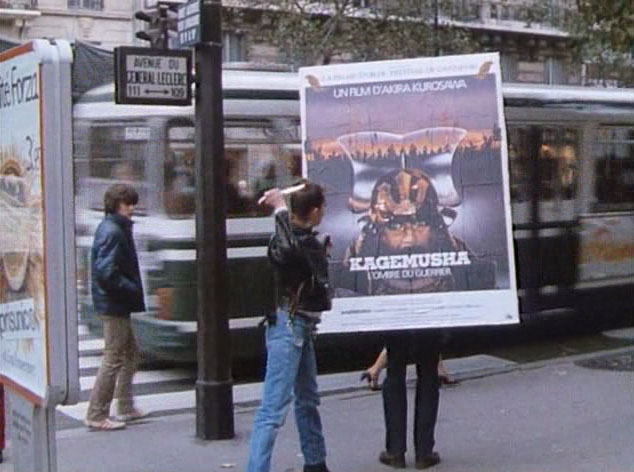

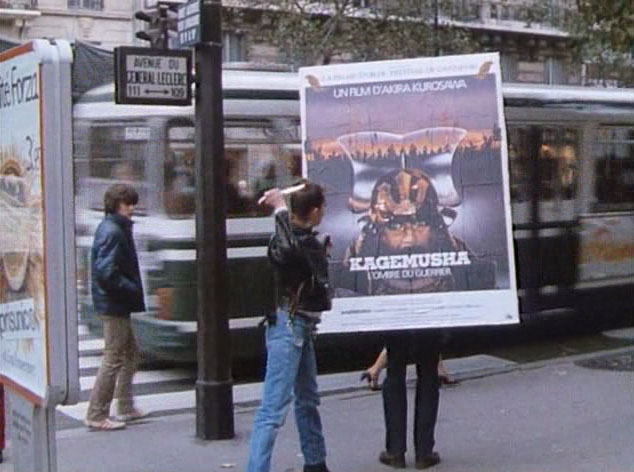

Knife-wielding Pascale vs. Kurosawa’s Kagemusha:

The Silent Scream, a spooky mansion flick:

The Big Country with Gregory Peck – in French it’s called “Wide Open Spaces”, as Pascale leads the claustrophobic Bulle into the theater for the night, to sleep close enough to the screen that she can’t see the walls

And on the way out of the theater…

Bulle Ogier stars in her fifth Rivette film along with Pascale Ogier, Bulle’s daughter, who also starred in a Rohmer movie and something called Ghost Dance before dying of a heart attack at age 26. Bulle, just out of prison, has a crippling claustrophobia and cannot step indoors, not even into a glass-enclosed phone booth, without feeling ill. Pascale, apparently homeless, hears Bulle’s story of getting caught up with the wrong crowd and sets out to keep it from happening again, tailing Bulle’s boyfriend Julien (Pierre Clementi of The Conformist, The Inner Scar).

Pascale seems to be on to something – they steal Julien’s briefcase and discover all sorts of newspaper articles about kidnappings and killings, and also a map of Paris that has been sectioned off in a spiral pattern which reminds Bulle of a “very frightening game” she used to play called the Goose game. They find a sort of key to the map on a murdered man in a cemetery and start to identify the “trap squares” in the game, beginning with places they’ve already been: Prison and the Tomb, then they proceed to play Paris like a game, hoping to survive all the trap squares and win the game.

Besides Julien, they keep running into a balding man (Jean-Francois Stevenin, the teacher in Small Change), who sometimes seems to be a companion of Julien’s and sometimes schemes with the girls independently of Julien, warning Bulle that the people responsible for sending her to prison are after her again. Pascale calls this man Max, her name for all the city’s conspirators. For example, when Bulle wonders about the explanation for the dead map-carrier in the cemetery, Pascale responds “The Max had a bullet in his guts – that’s the explanation.”

Discovering the murdered, bewigged Max

Each “trap” location presents a new challenge. At one, Pascale, who has a compulsion to carve the eyes out of advertising posters, is faced with a whole wall of those. At another, Pascale is in a fight with a white-haired Max who leaves her in a giant cobweb until rescued by Bulle, and at a third Pascale has to defeat a giant dragon, played by some sort of amusement-park ride with an added flamethrower.

While Pascale lives in this fantasy Paris, Bulle’s adventure seems more real and dangerous – she’s given a gun by Julien and keeps having to figure out whose side she’s on. Of course once a gun is introduced into the movie, someone has to get shot. Pascale kills a Max and seems unrepentant, and then Julien kills Bulle, telling her “I loved you.” But the movie’s sympathies have turned towards the inner life of Pascale – she meets Max on a bridge over the river, and they spar together, appropriately practicing “Katta – a combat against imaginary enemies.”

I was tempted to see the sparring scene above as evidence that Pascale was working alongside the Maxes all along, but no, I think she’s just an erratic character. Anyway, it wouldn’t have taken a city-wide conspiracy including Pascale to defeat the fragile Bulle.

Good one by F. Ziolkowski:

Marie’s belief in a great love with Julien, the real at the end of her quest, will eventually be fatal for her. It is Baptiste’s ability to “roll with the punches” which will perhaps save her, but at what cost? As one of the Maxes puts her through a karate exercise and tells her to fend off “imaginary enemies,” the cross-hairs of a surveillance device (a rifle scope? a camera?) appear on the screen. “They” are now being watched by others, perhaps simply by us. That is, it may be that the answer to the riddle of the labyrinth — its last door — is simply the screen on which the actors’ shadows appear.

The movie got a hateful review in the Times, and was even dismissed by Senses of Cinema. Fortunately it’s not my job to analyze its quality in relation to other Rivette films, or even other films in general – I was just along for the ride, which I enjoyed.

Insight from J. Rosenbaum:

The file of clippings concerns specific scandals of the Giscard d’Estaing regime, and the locations refer to various municipal corruptions associated with that period (e.g., the ruins of slaughterhouses in La Villette which were built and then demolished before they could be used, due to safety hazards). Rivette has indicated that the film was made prior to the French elections and with the pessimistic expectations that the same regime would remain in power; so the unexpected election of Francois Mitterand obscured and blunted part of the film’s intended impact. Rivette conceived of Marie as a continuation of the anarchist character played by Bulle Ogier in Fassbinder’s The Third Generation (1979), after she gets out of prison. Her claustrophobia was occasioned by the film’s cut-rate budget, which led to the decision to shoot the film exclusively in exteriors.

Ziolkowski again:

[Paris] for the Surrealists was not only a magical place, it also became a living organism, a protagonist in its own right, complete with motivations, deaths, rebirths, etc. … The group’s fascination with the myth of the labyrinth led them to name their most prestigious and influential review Le Minotaure. … All the elements of Surrealism are here once again: the double, the lions of the Place Denfert-Rochereau which seem ready to spring to life at any moment, the mysterious stranger who crosses one’s path in the middle of the night.

Follow the gun.

From Julien…

… to Bulle …

… to Pascale

Julien again (different gun)

Rivette: “The idea was to refer to Don Quixote and Sancho Panza. Passing from the Parisian quartiers outward to the peripheral areas, within those zones that are slightly uncertain, but without ever leaving Paris. We also wanted to show everything that was in the process of being transformed, under construction.”

Bulle and Julien atop the Arc:

–

Paris s’en va (1981)

“Paris Goes Away,” a half-hour movie made from scenes and outtakes from Le Pont du Nord. A narrator tells us about the Goose Game, often repeating as the images also double back on themselves. It’s a mini-Spectre version of the feature, more lightweight, with more lingering shots of monuments and less danger and conspiracy. The narration seems to imply that Bulle’s flask is her game token. Rivette’s only other short that I’ve seen, Le Coup du berger, also referenced games, if that means anything.

Le Lion Volatil:

Pascale:

Bulle:

–

Jacques Rivette, Le Veilleur (1990, Claire Denis)

“Artists have a portion of basic villainy, even the greatest of them.”

Agnes Godard (still Denis’s cinematographer two decades later on 35 Shots of Rum) shoots critic Serge Daney (he took over Cahiers after the Bazin/Rohmer era) in conversation with Rivette, in Parisian cafes and fields. Divided into two parts, “I – Day” and “II – Night.”

“Do we see his painting or not?” Jacques discusses preliminary thoughts on Le Belle Noiseuse before he had worked out the story or approach. Le Pont du Nord gets the most discussion time, strange, since he’d made three movies since then (Love on the Ground doesn’t get a single mention). I wasn’t crazy about the music in Le Pont du Nord so I’m glad to hear that he spent very little time selecting it.

Rivette with Serge Daney:

I wouldn’t call it a great film (sorry, Claire Denis) but it’s a great interview/conversation, worth watching again, not like a throwaway DVD extra. Loooong shots include the silences between questions, perhaps in deference to Rivette’s own long-take style. He tells of his early years, first arriving in Paris, meeting up with Rohmer, Truffaut and Godard and going to work for Cahiers with Bazin. He discusses duration in a “post-Antonioni world,” saying movies used to have pre-determined beginnings and endings and filmmakers were free to fill the middle with events, but now it seems there are fewer rules and everything takes longer to say. When asked what he’s enjoyed lately in theaters he highly recommends a Sandrine Bonnaire film called Peau de Vache.

“I don’t want to separate, to split things up. I know a lot of filmmakers, whether consciously or not, who have this notion of splitting the body into bits. Not just the face, it can be the hand or any part of the body. I always want to see the body in its entirety. I don’t have the temperment, the taste or the talent to make heavily edited films. My films focus more on the continuity of events taken as a whole.”

Time out for an interview with Le Pont du Nord’s Max, Jean-Francois Stévenin, including his entire scene as Marlon in Out 1.

Rivette again: “My feeling is these people who have been affected [by his films], and who have these individual ways of showing that, they constitute a kind of widespread secret society. We’re obviously not talking about lots of people, unfortunately for the film producers!” He talks with his hands, striking wonderful poses.

In part 2, Bulle Ogier is along for the ride, interjecting a word or two, only getting the camera to herself for a few minutes.

Serge: “When you came back to earth with Pont du Nord in the early 80’s, it was with the feeling that we adapt to things as they are, we stop tempting fate or playing Prometheus and we come back to the real world. And we remember that the beginning of the 80’s were roaring, euphoric, entertaining – very explosive, in fact. And your film takes that on board. We can feel something quite intentional in the processes which make up Le Pond du Nord and allow you to tackle the 80’s.”

Rivette’s vogue poses:

Rivette:

It’s a time when we feel such a decision has been taken. Just as Bulle said at the end, ‘I’m alive.’ As far as I’m concerned, and I have the impression that, strangely, it concerns – I won’t say everyone, there are always exceptions – many filmmakers of my generation and subsequent generations. After Out, it seemed impossible in my films to talk about the contemporary world, what we call the real world, and at that time I wanted more than anything to work on fiction, fantasy fiction films. I didn’t shoot them all because the first project was, after Out and Celine & Julie, was a film we wanted to do with Jeanne Moreau [Bulle: “Phoenix.”] and Juliet Berto and Michel Lonsdale, which was a story based on the Sarah Bernhardt myth loosely mixed up with Gaston Leroux’s Phantom of the Opera. And what came next were stories that were all different with one thing in common: the total refusal of France in the seventies. It was something I suddenly didn’t want to see anymore. And after a series of events, more or less successful films – some were far from being completely successful, unfortunate films, at least Noroit and Merry Go Round were, that were hardly seen anywhere. They were shaky films, it’s true. When I went to see Bulle and said ‘We have to do another film together and I want to do it with you,’ it was the idea that we hadn’t put these bad times behind us, that they may well continue, and we had to come to terms with it but in order to do that we had to turn it into fiction, to put it in a film. And that’s why, in Pont de Nord there’s this insistence – that may appear anecdotal ten years after – on the affairs or scandals at the end of the seventies, such as the Debreuil affair or the suicide or non-suicide of Boulin or the killing of Mesrine, that sort of stuff. As symptoms, but strong symptoms. And we shot the film, at least from my point of view I began the film, not in this atmosphere of eighties euphoria we mentioned but with the impression of being in a country – France – that was stuck. Stuck, because of a lot of things we won’t go into here – everyone remembers. But it so happened that this feeling of being stuck was so strong that it brought about a certain unblocking.