I read very little about this, conscious of spoilers, but certain things, as with Antichrist, were unavoidably overheard (or given away in the trailer). So I knew it was set near the start of WWI and that the evil children in the trailer represent the birth of fascism, but I didn’t realize how subtly that point is made. There are unexplained events, the children increasingly seem responsible, then some major characters disappear and the narrator leaves town, with no ends neatly tied up.

Two things for sure: it’s an excellent movie and the camerawork (DP Christian Berger, his fifth with Haneke) is perfect, beating Cache by a mile. Apparently was shot digitally, in color, then post-processed. Very classic feel to the entire production, except to the acting, especially of the children, which is better than anything from the WWI or WWII eras (sorry, Wild Boys of the Road). Won awards almost everywhere (the BAFTAs preferred A Prophet and oscars preferred something from Argentina), beating out Basterds, Antichrist and Wild Grass at Cannes.

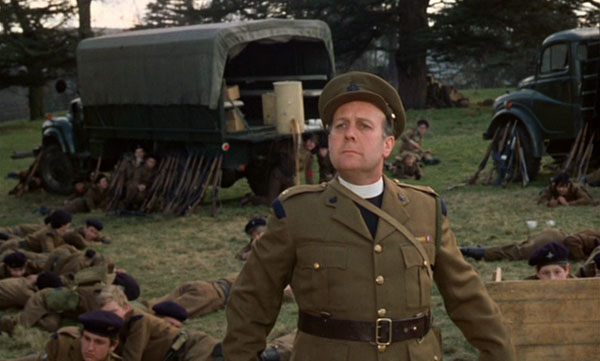

Interesting to have a non-omniscient narrator, schoolteacher Christian Friedel, who goes on long sidetracks from the town mysteries to chase after a girl, nanny of the baron’s young twins. Town authority figures are painted as corrupt. The doctor (Rainer Bock, small role in Inglorious Basterds) is abusive and perverse to his daughter and to his girlfriend (Susanne Lothar, lead in Funny Games). The pastor (Burghart Klaussner, was just in The Reader) is a tyrannical father. The baron (Ulrich Tukur, The Lives of Others) exercises his power to throw families into poverty at will. The children don’t exhibit the usual responses of sullenness, fighting and petty power games, but band together to commit acts of planned vengeance, terrifying the town. Their crimes go officially undiscovered and unpunished at the end, Haneke’s point, I suppose, being that they grew into fascists and nazis.

There is, of course, an absolute ton written about this movie already. The Times says “it lacks the intellectual and emotional nuance that would make this largely joyless world come to life,” but that’s just the common criticism that Haneke’s films are cold and unfeeling, which applies less to this film than to his others so I don’t see the point in bringing it up.

Indiewire: “With this detailed exploration of anonymous retribution, Haneke returns to the haunting terrain he last explored in Cache, although in this case, the retribution expands from a personal level to a larger critique of religious zealotry. … However, these events remain notably off-screen. Absence in The White Ribbon is the quality that makes it a harrowing work of art, rather than a historical soap opera.”

Salon: “It definitely can’t be reduced to a fable about the roots of fascism. The White Ribbon is a dense account of childhood, courtship, family and class relations in a painfully repressed and repressive society, which seems to channel both early Ingmar Bergman and the Bad Seed/Children of the Corn evil-tot tradition.”

Haneke:

The film opens with the narrator saying, “I’m not sure if the story I’m about to tell you corresponds to what actually took place. I can only remember it dimly. I know a lot of the events only through hearsay.” So both those elements, then, raise mistrust in the audience as to the accuracy of what they’re going to be seeing, and the reality of what they’re going to be seeing. Both the black-and-white and the use of a narrator lead the audience to see the film as an artifact, and not as something that claims to be an accurate depiction of reality.

It’s only in mainstream cinema that films explain everything, and claim to have answers for anything that happens. In reality, we know so little about what happens. It’s far more productive for me to confront the audience with a complex reality that mirrors the contradictory nature of human experience.

I remember with my first film that was shown in Cannes, The Seventh Continent, there was a screening and afterward we had a discussion. The first question came from a woman who stood up and asked, “Is life in Austria as awful as that?” She didn’t want to accept the difficult questions being raised in the film, so she tried to limit them to a specific place and say, “That’s not my problem.” You could make the same mistake with this film, if you see it as only being about a specific period.