Maria flees her town and moves into a house in the woods along with two pigs that she transforms into children and names Pedro and Ana. I think they’re hiding from a wolf outside, and after they almost die in a house fire Pedro drinks honey and turns white, and Ana swallows a songbird and gets a golden voice, then Maria is rescued after they try eating her… I dunno, I was too busy marveling at the look of this thing.

Smeary, drippy painting inside a real (model?) house, with doorways and props. But painted scenes will overwhelm doors and props as if they weren’t there, then form free-standing stop-motion models within the room, 2D artworks interacting with 3D objects, the wall art constantly shifting and the models always making and unmaking themselves, styles of the characters changing. Rustling and rubbing sounds accompany all the visual shifting, wires and cellophane hold the models in place, and I think it’s all fluid transitions with no traditional editing.

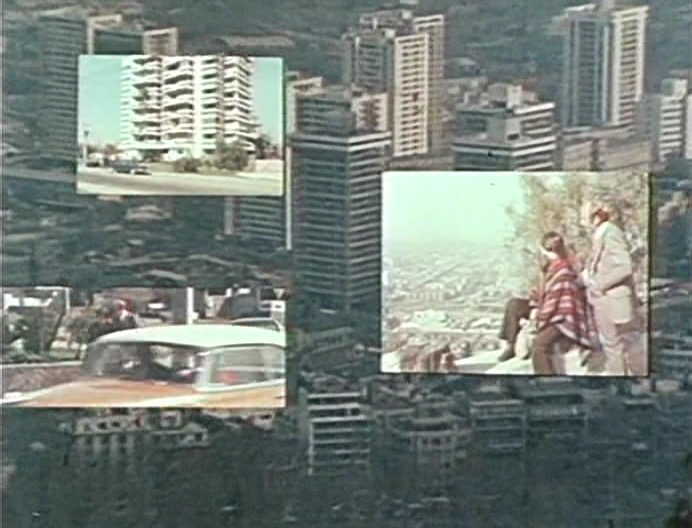

I’d forgotten about the brief TV-footage framing story, but did wonder why Maria sometimes spoke German. Apparently this is a fairy-tale reference to a notorious German-led cult and Pinochet torture compound, active in Chile for decades.

Cartoon Brew:

During the research process, the filmmakers discovered that the German members of the community used to call their Chilean neighbors ‘schweine’. This led them to conceive of the two children in the story as piglets, and depict their progressive transformation into Aryan humans as an ironic joke aping the community’s racial ideology.

Walker has an interview with the directors, including some amazing production details, and their self-set rules for animation and sound design:

We had a literary script, with the dialogues of the film, a really simple storyboard, basically with one image per scene … Our day-to-day work was to find a way to connect one image with the other … The specific actions of each scene were improvised.