Plaisir d’amour en Iran (1976)

An expanded version of Pauline and Darius’s trip to Iran in L’Une chante, l’autre pas. Pauline and a narrator comment on the sensuality of Persian architecture. I would’ve liked it if the feature had been edited more rhythmically like this short (or if the picture quality had been as good).

Du Coté de la Côte (1958)

Fun, half-hour exploration of tourism along the coast, more gentle than Vigo’s À propos de Nice and simpler than a Marker travelogue.

“These parks, overpopulated with merry people attracted by the Latin shore, foreshadow the dead people seeking eternal rest there. In both cases, space is limited because of its good quality. It is a well-rated coast.”

Les Fiances du pont Mac Donald (1961)

The short within Cleo from 5 to 7 is apparently considered its own little film. “I wanted to provide a little relief for Cleo. … So I thought at the beginning of the third part of the film, where films often have a lull, a weakness, a slow-down … I would introduce something uplifting. My other goal was to show Jean-Luc Godard’s eyes. At the time, he wore very dark glasses. We were friends, and he agreed to this little story about glasses in which he must take them off and reveal his big, beautiful eyes, like Buster Keaton’s.”

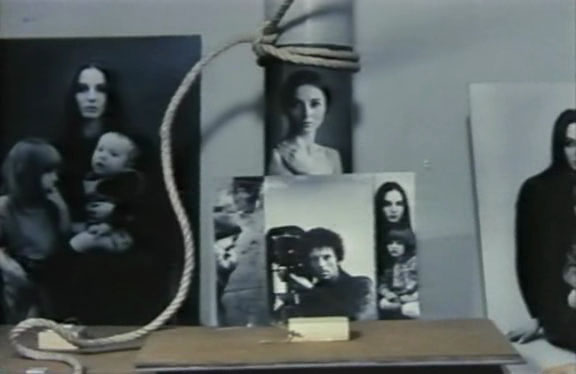

Ulysse (1982)

This was fantastic. Varda finds an old photo of hers, taken in 1954, and investigates. What was she thinking about at the time? What were the models in the photo thinking? She looks them up and asks. Agnes: “This almost painful investigation taught me so much about what an image says, what it says to each of us, and what it cannot say. It merely represents.”

AV: “How does she see her own goat image? Without making animals talk, like in American cartoons, or defining memory as a rumination of mental images, may I suggest that there is an animal ‘eatingmagination,’ a self-predatory imagination?”

Salut les cubains (1963)

Months after Cleo from 5 to 7 opened, Varda went to Cuba to photograph the country’s inhabitants for an exhibit which opened in Havana (introduced by Raul Castro!) before it moved to Paris. She also made this film out of the photos, narrated by Michel Piccoli. Subjects include the Castros, famous national artists, workers, dancers, posters and drawings and artworks. She creates action sequences, animating the photos, best of all with this guy dancing for the camera.

Mentions Marker’s Cuba Si, which came out a couple years before. In her introduction, Varda says twice that “we must place it in the context of 1962,” since the Cuban dream society didn’t turn out the way the French leftists hoped it would. Interesting that she made such a happy, idealist film as this, then her next feature would be the happiness-breakdown of Le Bonheur.

These last two were reissued in the 2004 collection Cinevardaphoto with a third, current short about a teddy bear collector, but somehow I didn’t have subtitles for that one. If Cleo from 5 to 7 and L’Une chante, l’autre pas revealed Varda’s kinship with the filmmaking of husband Jacques Demy, these shorts represent a definite (and oft-mentioned) kinship with Chris Marker, and either of them could stand alongside his best documentaries. The commentaries are more personal, less consciously witty. The images are wonderful, and the sense of investigation, of images and memory, the psychology of the films puts them on the Marienbad and La Jetee side of the new wave fence… my favorite side.

Elsa la rose (1965)

A portrait of Elsa in the words of her husband Aragon, who has spent their entire relationship writing and publishing poems about her. Varda calls them a “famous couple and fervent communists.” Elsa is filmed as Aragon imagines and remembers her, says she repeated the exercise with her own husband for Jacquot de Nantes. In voiceover, Piccoli reads the poems as fast as he can, a hilarious idea. First movie Lubtchansky and Kurant shot for Varda.

Elsa: “The readers of these poems expect me to be 20 years old forever. As I cannot satisfy this need for beauty and youth that the readers have, I feel guilty and it makes me unhappy. That’s what’s terrible, they’re not just for me.”

ReÌponse de femmes (1975)

“Women must be reinvented.”

Agnes has a few minutes to state the case of all women, socially and politically. Lots of nudity, which she points out is not exploitative unless used to sell a product or titillate viewers.

Coming attractions (when I’ve got subtitles): Black Panthers (1968)