Wonderful 16mm screening at Emory, but not well-received by the students and regulars who came to be entertained. Silly students and regulars, it is not a university’s job to entertain you!

Scorpio Rising – 1964, Kenneth Anger

Couldn’t remember if I’d seen this before, but of course I have… opening credits bedazzled onto a motorcycle jacket were immediately familiar. Despite the nazi imagery and comparisons between bikers headed for a gay orgy and Jesus and his disciples, I heard no complaints. I think people enjoyed the juxtapositions (well-prepared presenter Andy warned us about ’em in advance) and grooved on the hot 60’s rock radio score (kept hearing “oh I love this song” from behind me).

Lemon – 1969, Hollis Frampton

Lovely film, second time I’ve seen it. Should be shown every year. Only comment overheard: “I don’t know about the second movie. Just a lemon.” Mostly people were quiet about this one. I choose to believe that they were awed into silence, contemplating its light play and imagining possible deeper meanings, and not quietly wondering what they needed to pick up at the grocery store. A movie can feel much longer or shorter than it is. Lemon is supposed to be seven or eight minutes long, but I say it feels like four, five tops.

Zorns Lemma – 1970, Hollis Frampton

(no apostrophe, in tribute to James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake)

Okay, this one feels its length… its exact length, measured second by second.

1) Black screen, voice reads us some children’s poetry, each line beginning with a successive letter of the Roman alphabet (so I=J and U=V) to make 24.

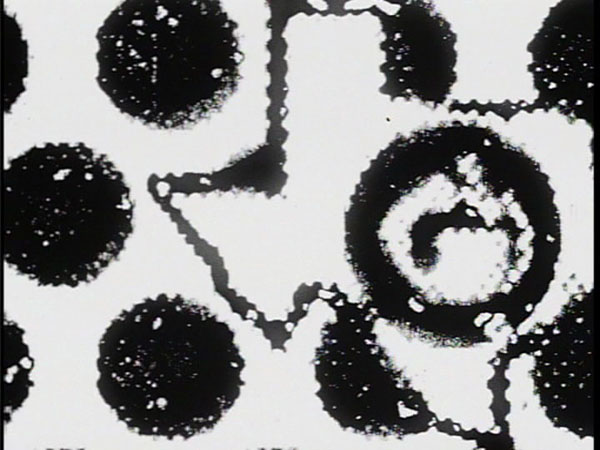

2) The meat of the piece, 24 seconds, one letter per section. First section we see each letter once. Then a word beginning with each letter. Then again (different shots, different words). Again. Again, but X has been replaced by a shaking, roaring fire. Again, with the fire. Again. Again. Again, but Z has been replaced by the ocean, flat horizon, a wave rolling out to sea. Again with the fire and the ocean. Again. 24 letters at 24 frames per second (though it’s 25 seconds if you consider that each alphabet section is followed by a second of black, a shout-out to our PAL-locked buds in Europe who see everything on video a little faster than we do). And on until, some 40 minutes later, each letter has been replaced (C was the last to go). No audio except the groaning and laughter of my fellow filmgoers.

3) Sound and Vision together! A visual cooling-down after part two, two people and their dog walk across a snowy field from bottom of the screen to top as six alternating female voices on the soundtrack read us some philosophical writings about light – at precisely one word per second.

4) The audience members (those who hadn’t walked out) were horrified!

D. Sallitt liked it:

The bizarre experience of taking a test during a movie was completely distracting, so that I absorbed the materiality and the narrativity of the alphabet images only indirectly, during brief rest periods. Somehow this strengthened my investment in the images: I don’t think I would have found the “letter H” guy’s walk around the corner very interesting in itself, but that corner took on mythic spatial qualities for me.

Hahaha, I know what he means about the corner. Of the little movies that replace each letter, seen in one-second increments, some stay pretty much the same (the fire, the tide) and some progress as time passes (someone peels and eats a tangerine, this guy walks towards a corner). Everyone breathes a little sigh of relief when, finally after a half hour, the man disappears around the corner in a one-second bit toward the end. Next bit is just the corner. Next one the man comes back around the corner! Must be considered one of the biggest twist endings in non-narrative avant-garde cinema.

excerpts from S. MacDonald:

Even a partial understanding of Frampton’s films requires a rudimentary sense of the history of mathematics, science, and technology and of the literary and fine arts. … Nowhere is Frampton’s assumption that his viewers can be expected to be informed, or to inform themselves, more obvious than in Zorns Lemma, the challenging film that established Frampton as a major contributor to alternative cinema. Zorns Lemma combines several areas of intellectual and esthetic interest Frampton had explored in his early photographic work and in his early films. His fascination with mathematics, and in particular with set theory … is the source of the title Zorns Lemma. Mathematician Max Zorn’s “lemma,” the eleventh axiom of set theory, proposes that, given a set of sets, there is a further set composed of a representative item from each set. Zorns Lemma doesn’t exactly demonstrate Zorn’s lemma, but Frampton’s allusion to the “existential axiom” is appropriate, given his use of a set of sets to structure the film. Frampton’s longtime interest in languages and literature is equally evident in Zorns Lemma. …

The tripartite structure of Zorns Lemma can be understood in various ways, at least two of them roughly suggestive of early film history. The progression from darkness, to individual onesecond units of imagery, to long, continuous shots. … If the second section of Zorns Lemma is Muybridgian – not only in its general use of the serial, but because the one-second bits of the replacement images “analyze” continuous activities or motions in a manner analogous to Muybridge’s motion studies – the final section is Lumieresque.

As set after set of alphabetized words and their environments is experienced, it is difficult not to develop a sense of Frampton’s experience making the film. The film’s collection of hundreds of environmental words suggests that the film was a labor of love, and an index of the filmmaker’s extended travels around lower Manhattan, looking for, finding, and recording the words.

For most viewers the experience of “learning” the correspondences is fatiguing – especially since the process of watching sixty shots a minute for more than forty-seven minutes is grueling by itself – but the laborious process has been willingly (if somewhat grudgingly) accepted. The experience of learning the correspondences is the central analogy of the second section. It replicates the experience of learning that set of terms and rules necessary for the exploration of any intellectual field.

In a philosophic sense, Grosseteste’s treatise [spoken during the third segment] is an attempt to understand the entirety of the perceivable world as an emblem of the spiritual. And, on the literal level, what Grosseteste describes in the eleventh century is demonstrated by the twentieth-century film image: For a filmmaker, after all, light is the “first bodily form,” which, literally, draws out “matter along with itself into a mass as great as the fabric of the world.”