This will be one to watch again when I know more French, or just when I’ve lived longer.

–

Chapter 1(a), “Toutes les histoires” (“All the (Hi)stories”)

Dedicated to Mary Meerson (Langlois’s companion who helped run the Cinematheque) and Monica Tegelaar (producer of Raoul Ruiz’s On Top of the Whale).

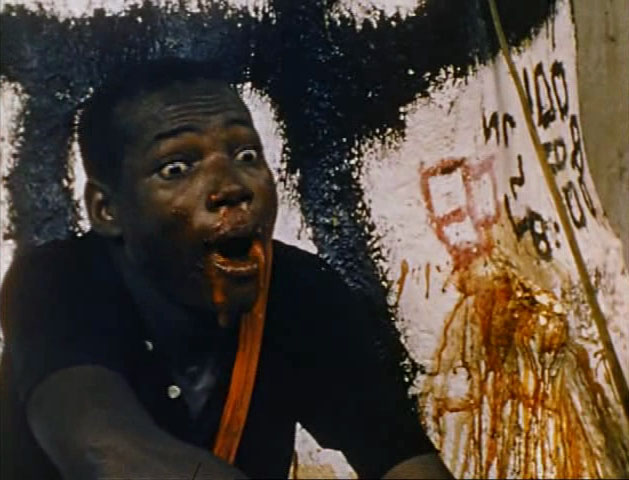

IMDB says parts one and two came out in the late 80’s, and the rest followed in the late 90’s. This one seemed more like a 50-minute trailer than an episode. Montage of archive footage, still and moving, edited and faded and superimposed and blended together. The footage includes scenes from films of course (rules of the game, great dictator, day of wrath, germany year zero) but lots of stills (producers, directors, Thalberg, Hughes) and paintings. Lots of focus on World War II, and ending with that Germany Year Zero segment, the whole thing came off as vaguely depressing. Maybe that’s why it took ten years to get the rest of the episodes made?

Three images overlapped: (1) Rita Hayworth dancing, (2) a drawing of Howard Hughes in his final days, (3) the witch-burning scene in Day of Wrath.

–

Chapter 1(b), “Une Histoire seule” (“A Single (Hi)story”)

Dedicated to John Cassavetes and Glauber Rocha (Brazilian director of Black God, White Devil).

Surprising number of references to Godard’s own films. Tons and tons of stuff I am not getting because I don’t know much French (I pick up half the film titles and some of the short sayings printed onscreen) or art history, and haven’t seen most of the films. Should’ve known better than to think part two would be more straightforward or make more sense. Even if I don’t know what it’s saying, I still get interesting juxtapositions of images and nice shots from great films seen and unseen, which is enough to keep me watching. Sounded like I heard some Leonard Cohen and Neil Diamond.

–

Chapter 2(a), “Seule le cinema” (“Only Cinema”)

Dedicated to Armand J. Cauliez (a writer, published a book on Jacques Tati) and Santiago Alvarez (Cuban filmmaker).

Fast-forward a decade. Same ol’ thing here, but two big changes:

(1) Not just montage of pre-existing footage edited with Godard in his study anymore. An actual actor, Julie Delpy, reading poetry. Also an interview with Godard by another guy (couldn’t be Serge Daney – he died in ’92), 90% untranslated.

(2) Me getting a little tired and pondering making my own historie(s) of cinema instead

–

Chapter 2(b), “Fatale beauté” (“Deadly Beauty”)

Dedicated to Michele Firk (film writer turned militant radical, killed herself in Guatemala to escape arrest) and Nicole Ladmiral (actress in Bresson’s Diary of a Country Priest).

Sabine Azema (above) recits some poetry, much of it untranslated. Godard types at his typewriter some more. I listened in the headphones and a background noise (JLG’s pet bird?) frightened me. Something about photography being invented in black and white as the colors of mourning to note the death of reality. And something about women, and murder, and Band of Outsiders and Rancho Notorious and Gone With The Wind. Good to see that Godard appreciates Tom Waits.

–

Chapter 3(a), “La Monnaie de l’absolu” (“The Coin of the Absolute”)

Dedicated to Gianni Amico (Italian filmmaker, assistant director on Bertolucci’s Before the Revolution and Godard’s Le Vent d’est & James Agee (film writer, champion of Chaplin’s Monseiur Verdoux, writer of Night of the Hunter and The African Queen)

or part 3A, the war and futility episode. WWII talk leads into an appreciation of Italian Neorealism and the most clearly presented introduction to a certain aspect of cinema and history thus far in the series. Says that Italian cinema in the 40’s and 50’s changed film like Manet (the godfather of modern art) changed painting. Closes with a nice montage of Italian film (minus too much onscreen block text and crazed fade transitions) set to a Richard Cocciante song. This episode has a clear point and meaning and narrative arc and supporting arguments… I don’t understand. Maybe the others have too, and I’ve been missing it. Juliette Binoche appears with Alain Cuny (of Les Amants and La Dolce Vita), who died in 1994, four years before this episode aired. Julie Delpy looked mighty young in her segment too – maybe all this footage was shot in the 80’s and not finished editing until ten years later.

–

Chapter 3(b), “Une Vague Nouvelle” (“A New Wave”)

Dedicated to Frederic C. Froeschel (head of a cine-club in Paris, 1950) and Naum Kleiman (Russian film critic, director of the Moscow Film Museum).

“Becker, Rossellini, Melville, Franju, Jacques Demy, Truffaut. You knew them.”

“Yes, they were my friends.”

A personal episode, sometimes celebratory but more usually melancholy. Godard himself is the guest speaker this time, but he’s actually into it, not just distractedly reciting behind his typewriter. These things never quite seem to begin, the opening titles still playing when the episode is half over. Some 400 Blows, some Henri Langlois, more goings-on about the death of cinema. What, is video the new art form?

–

Chapter 4(a), “Le Côntrole de l’univers” (“The Control of the Universe”)

Dedicated to Michel Delahaye (actor in Out 1, Alphaville, plenty more) and Jean Domarchi (1950’s, 60’s Cahiers critic, had a bit part in Breathless).

Another really good one. Probably not coincidentally, all the voiceover on this one is translated, so I was able to understand it. Lots of voiceover – it’s getting to be more of an essay lately and less of a purely visual slideshow. Still plenty of that dull video text, white-on-black block lettering. The thing always drags a little when JLG decides to move those words around the screen for thirty seconds before returning to the film clips. When there were clips, it seems half of them were by Hitchcock, “our century’s greatest creator of forms.”

–

Chapter 4(b), “Les Signes parmi nous” (“The Signs Among Us”)

Dedicated to Anne-Marie Miéville (one of Godard’s collaborators since 1976) and to Godard himself.

I hope nobody stumbles across this entry hoping to learn about the film, because I really doubt I understood most of it. More more more war images in this section (have I mentioned that the film is obsessed with WWII?) and more ponderings on love, death, art, history, man, the state, and Charlie Chaplin. And it seems to me that Godard is terribly depressed. Anyway, here’s a good bit of the voiceover from the last eight minutes:

I need a day to tell the history of a second…

I need an eternity to tell the history of a day.

We can do everything except the history of what we are doing. It is my privilege to film and live in France as an artist. Nothing like a country that every day walks further down the path of its own inexorable decline.

I am the fugitive enemy of our times. The totalitarianism of the present as applied mechanically every day more oppressive on a planetary scale. This faceless tyranny that effaces all faces for the systematic organization of the unified time of the moment. This global, abstract tyranny which I try to oppose from my fleeting point of view. Because I try, because I try in my compositions to show an ear that listens to time. And try to make it heard and to surge into the future.

The only thing that survives from one epoch is the art from it created. No activity can become an art until its proper epoch has ended. Then, this art will disappear. Thus, the art of the 19th century – cinema – made the 20th century exist, which barely existed.

Cinema feared nothing of others or of itself. It wasn’t sheltered from time. It was the shelter of time. Yes, image is happiness. But beside it dwells nothingness. The power of the image is expressed only by invoking nothingness. It is perhaps worth adding: The image, able to negate nothingness, is also the gaze of nothingness on us. The image is light. Nothingness, immensely heavy. The image gleams. Nothingness is that thickness where all is veiled. The most fleeting moments possess an illustrious past. If a man passed through paradise in his dreams and received a flower as proof of passage, and on waking, found this flower in his hand… What is there to say? I was that man.

Thought I’d watch the Cannes 1988 press conference, but after the first three minutes (“video artist” Godard passionately attacking television) it all turns French.

From a belatedly-discovered interview between JLG and J. Rosenbaum:

JR: Yes, but it also isn’t legally acknowledged that films and videos can be criticism.

JLG: It’s the only thing video can be — and should be.

With that strong distinction between film and video, it occurs to me that JLG considers Histoire(s) as being about cinema but not being a work of cinema itself. I watch Breathless on my TV and say I’ve seen one Godard movie, then I watch Histoire(s) on my TV and say I’ve seen two Godard movies. JLG should like to smack me for such a thought.