We follow Fini, a deaf/blind advocate who visits her people in different family and institutional situations. It’s almost a public-service issues doc, showing sad disabled people and explaining how systems have failed them. But ever since watching Little Dieter I’ve known that Herzog likes to take his doc subjects to unusual places, and who else would take a party of blind women to a cactus garden?

Vogel: “confirms Herzog as the mysterious new humanist of the 1970s, light-years removed from the sentimentality of the Italian neorealists and the simplistic propaganda of untalented documentary film radicals.”

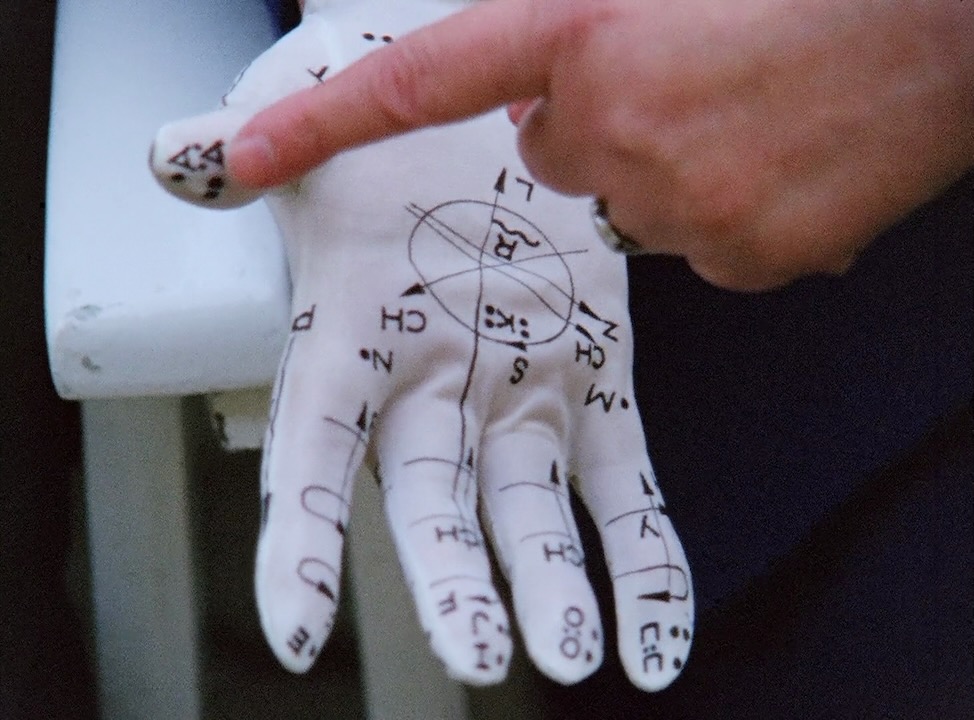

Hand communication: