2016/17: Watched the new blu-ray and updated the 2008 writeup below.

The brother of Morag (Geraldine Chaplin, then of CrÃa cuervos and The Three Musketeers, later of Love on the Ground and Talk To Her) is killed. She seeks revenge on pirate queen Giulia (Bernadette Lafont, Sarah in Out 1, also Genealogies of a Crime), infiltrates the castle with help of traitorous Erika (Kika Markham of Truffaut’s Two English Girls and Dennis Potter’s Blade on the Feather). Gradually all of Giulia’s associates are killed off, then G & M stab each other to death, fall to the ground dying and laughing.

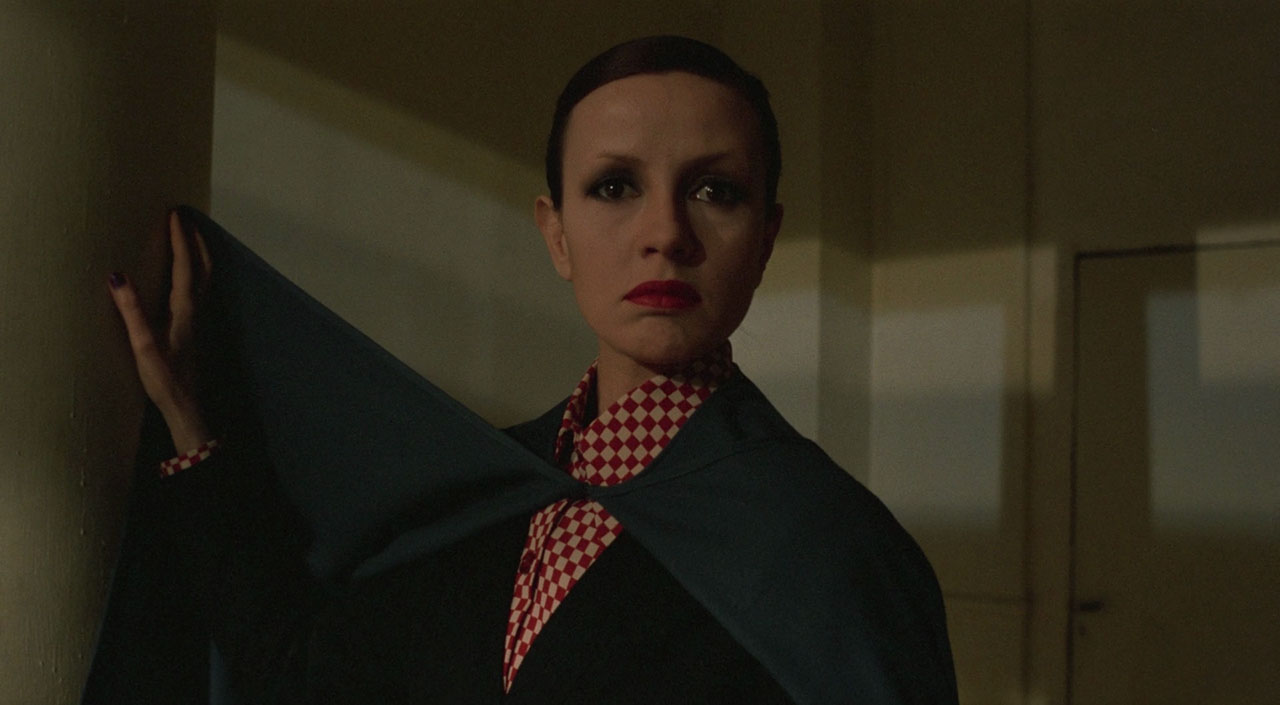

Early ambush attempt:

Feels more mysterious and less straightforward than Duelle even though there’s less talk of magic in this one. Morag is apparently the moon goddess and Giulia the sun goddess, though they don’t reveal their powers until the last half hour. I didn’t do the best job keeping track of the minor characters, but I’m almost positive that some of them – including Morag’s brother – keep dying then reappearing in later scenes. In fact, I guess one of the two male pirates, “Jacob” (Humbert Balsan of Lancelot of the Lake, later an important film producer) is also her brother “Shane,” which complicates the plot in ways I no longer understand.

The men of the castle, Jacob and Ludovico:

There are gas lamps and castles and swordfights and magic, all very period, but then there is lots of cool, modern (clearly 70’s) clothing and guns and motorboats. And nobody is cooler than Bernadette Lafont in her bellbottomed pink leather suit (which creaks loudly when she moves). Watching her and Chaplin’s movements through the scenes, and to a lesser degree the other male pirate Larrio Ekson, are the best part of the movie and sometimes appear to be its entire point.

As beautiful and simple as the sun: Giulia with pink jeans on:

Morag and Erika have meetings in which they sit or walk robotically and recite lines in English from the play The Revenger’s Tragedy, so maybe reading that would help somewhat. Then again, D. Ehrenstein says “Analysis begins to run into a series of dead ends. The texts utilized as central sources of quotation… Tourneur’s The Revenger’s Tragedy in Noroît — are merely pre-texts, having nothing to say about the films that enclose them, posed in the narrative as subjects for further research.”

As in Duelle, whenever there’s music in a scene the musicians are part of that scene, even when they realistically would’ve left the room. Maybe right before the shot begins Giulia has threatened their lives and told them to play, no matter what. There are long stretches with no spoken dialogue. Lighting mostly looks natural indoors. This and Duelle were Rivette’s first films shot by William Lubtchansky, who would shoot most of the rest of the films (not Hurlevent). William is husband to Nicole L., who edited everything for forty years from L’Amour Fou to Around a Small Mountain.

Morag killing Regina:

Erika playing Morag in the reenactment of previous scene:

Morag playing Regina getting killed by skullfaced Erika:

I wish I knew how this movie’s title was pronounced, because every time I think of it, Fred Schneider sings “here comes a narwhal!” in my head. It’s gonna be “narr-WHAA” until some Frenchman tells me otherwise. One site translates the word as “Nor’wester.”

Rivette:

When I was filming Noroît, I was persuaded that we were making a huge commercial success, that it was an adventure film that would have great appeal … When the film didn’t come out, when it was considered un-showable … I was surprised. I don’t consider myself … unfortunately, I’m not very lucid when it comes to the potential success of my projects.

J. Reichert:

As with all good revenge dramas (this one inspired by bloody Jacobean plays), the mass of killings begin to far outweigh the initial wrong done and the angel of vengeance experiences moments of doubts and sympathy for her marks—there’s betrayal as well. Rivette shorthands these narratively rich moments, suggesting them in a glance, a line, a change of Chaplin’s face, so that he can maintain focus on the ballet-like movement of his players through space, where stowing recently acquired treasure takes on the aspect of slow-motion acrobatics. The drama climaxes in a clifftop masquerade ball/murder spree/dance performance shot across what looks like infrared, B&W, and color, that combines violence and poetry into a mix that’s literally unlike anything I’ve seen.

Doomed dance party:

Giulia (left) and Morag having stabbed each other to death:

D. Ehrenstein:

The films are devoted to methods that while seeming to reach representational specificity, do so in a manner designed to cancel all possible affectivity. The settings and costumes of Duelle suggest their display in a reserved “theatrical” style, but the camera, while tracking smoothly, does so far too energetically, and when coupled with the film’s nervous angular montage rhythms, disrupts the space it has spent so much time constructing. Likewise each setting (casino, hotel, aquarium, ballet school, race track, park, subway, dance hall, and greenhouse in Duelle, castle by the sea in Noroît) suggests the possibility of an atmosphere the mise en scene never seems directly to create (as in Resnais, Franju, Fellini, etc.).

Similarly acting styles clash with one another. Flip off-hand cool (Bulle Ogier, Bernadette Lafont) wars with highly stylized affectation (Hermine Karaheuz, Geraldine Chaplin) rather than the work holding to the latter mentioned category for an overall tone as would be logically demanded by a project of this sort … The film’s essence is thus not reducible to a specific moment, but must be seen in the working through of its positive/negative gestures — unfixed points neither within nor without the films.

Poster shot: Morag and Shane… or is it Jacob?

Michael Graham:

Like any Rivette film, [Noroît] took shape gradually, drawing on a large number of deliberately chosen ideas and as many fortuitous circumstances. As important as Rivette’s interest in Tourneur’s The Revenger’s Tragedy (drawn to his attention by Eduardo De Gregorio), and the curious traditions surrounding the period of Carnival, was the availability of Geraldine Chaplin and Bernadette Lafont together with that of a group of dancers from Carolyn Carlson’s company. It must be kept in mind that Rivette often conceives a film around particular people; Celine et Julie began as ‘a film for Juliet Berto’. Any casting decision is consequently of primary importance. Further, the selection of Brittany as a location arose as much from certain union allowances permitting a six day week outside Paris, as from a vague desire to spend some time in the country. Once the different ideas and practical considerations begin to sort themselves out and interact, the narrative itself starts to acquire definition. Even after shooting has begun, however, Rivette is enormously influenced by what he may discover the actors capable of achieving.