Nausicaa (1971)

Episodic in different styles, like The Silence Before Bach, and more engaging about Greece than her friend Chris Marker’s The Owl’s Legacy. A big improvement over Lions Love. Varda’s last movie before Mathieu was born and she took a few-year break, returning with Daguerrotypes.

Interview with Pericles, arrested and tortured in Greece after the 1967 coup. Flamboyant sketch about greek art led by advertising guy Mr. ID, jeered by an unseen audience when it ends. Salesgirl selling greek art books instead of bibles (of course you can pay in installments). Newscaster-like guy gives us a history lesson on the coup. Interview with a greek soldier who fled. A geologist found work as a night watchman, misses the sun and the sea, his friends and family now in prison.

Varda makes her first appearance in the next segment, a gathering of exiled Greeks, and a drama starts to come together. We get a recurring character in the salesgirl, and some scripted drama as a young Gerard Depardieu steals her books. The girl and her roommate are hosting a Greek refugee journalist in her apartment until he can get his own place.

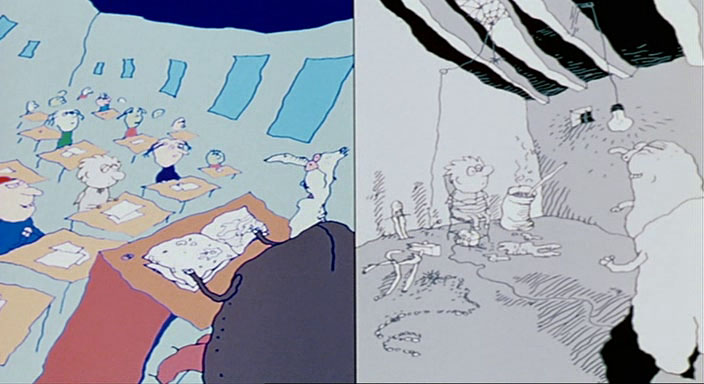

Street interviews with tourists who love Greece and don’t think about the politics, and a visit to the Club Med office. A scene purportedly set in Greece, but the backdrop of sea and mountains is transparently fake. Narration by one of the guys who tore down the nazi flag from the Parthenon during WWII. Skit with a girl named Democracy being whipped by her authoritarian mother, asked to sign a loyalty oath.

Democracy hiding under the table:

Episode narrated by Varda about her family history. She talks about a harbor trip she took with the actor playing the refugee journalist, throwing her producers under the bus for not having enough crew to capture sound on their trip.

A factory secretary tell the journalist her secret family history – she turns out to be the mom of one of his hosts, the one from Golden Eighties. After he sleeps with the non-Eighties girl, instead of having them speak to each other, Varda reads both their lines from the script as narration.

–

Documenteur (1981)

A vaguely depressing one, made during Varda’s second Los Angeles residency, the same year as Mur Murs (and also interested in street murals). Sabine Mamou (Varda and Demy’s editor) and her son (Mathieu Demy) are in LA, she is a typist bouncing between residences, staying with friends until she gets her own place. The movie is very into watching local people, not clear where the actor/documentary line is drawn, with wordy narration, full of wordplay and association.

–

Pasolini/Varda/New York (2022)

Shot on a walk through NYC in 1966, with sound and editing done the following year, then lost until Rosalie restored it in 2022. Pasolini has essential thoughts about New York and filmmaking.

–

Ô Saisons, Ô Châteaux (1958)

Maybe her most picturesque movie, an elegant tour of fortresses and castles, with a light jazz soundtrack and poetry excerpts. Torn between thinking this is great and thinking it’s a piece with the tupperware advertisement she directed. Reading the Carrie Rickey book now, which says this was an important step in getting Varda connections and respect and funding for her next steps after La Pointe Courte.

–

One Minute for One Image (1983)

Commentary on photographs by (mostly) other artists. Old woman’s face, naked boy held by old women, boats with person in foreground, hand surgery, family in open house, mass grave (this has second narrator Jacques Monory), handshake with fish hand (below), family portrait (with guest commenter Agnes’s mom), mud wrestling, hippie facing soldiers, mirror shard and purse contents on street (a still from Cleo from 5 to 7), kids on a Chinese wall, nude mirror polaroids.

–

Les Enfants du Musée (1964)

Short doc of a youth program at the museum for aspiring artists.

–

Les 3 Boutons (2015)

No shade on Varda, this is just an overpriced fashion commission. Teen girl leaves her goat farm after receiving a package full of magic fabric, floating through the city in a robe, losing three buttons and gaining three wishes. Good color, nice focus tricks, and standard ugly CG. Also checked out the DVD extras/follow-ups to Daguerrotypes and a couple others – there is a wealth of material on Criterion.