Feather Family (2023 Alison Folland)

Mashup of backyard children home movies (distressed film) and glitchy 3D bird-based video game (clipping, strobing). The hawk eats a pigeon, the kid’s broom has googly eyes.

–

Mockingbird (2020 Kevin Jerome Everson)

Watching the watcher: very shaky handheld of a Mississippi Air Force guy looking through binoculars. Sadly, no birds appear, at least none I could make out.

–

Ornithology 6 (2021 Bill Brand)

Ugly green fence footage splintered into pieces, vaguely in the shape of a flock of birds. Silent, endless.

–

NYC RGB (2023 Viktoria Schmid)

Static shots of interior/exterior buildings with light and shadows refracted into rainbows, really cool effect, ambient soundtrack. Clouds and traffic are not immune to the rainbowing.

–

A Portrait of Ga (1952 Margaret Tait)

Her mom smokes outside while gardening and hanging out, and she smokes inside while having a half-melted hard candy. Light narration, nice color, file alongside Mr. Hayashi.

Cayley James in Cinema Scope:

A series of portraits and close readings of the places she called home, Tait’s “film poems” (as she called them) invite the viewer into a familiar but altogether hypnotic vision of everyday life. While there is an air of the home movie about the movement of her handheld 16mm camera, there is something far more exploratory here than in the average diary film … In this foundational early work, Tait’s camera is drawn to things that would become her visual vocabulary throughout her career — hands, bird calls, flora and fauna, the cut of a dress — while eschewing the easy route of picture-postcard views afforded by Orkney’s windswept landscapes.

–

Information (1966 Hollis Frampton)

More like interlaced-formation, ugh. The intended image is lost by being broken into video-stripes, but the intended image is just wiggly white flashlight dots on a black background, silent.

–

Prince Ruperts Drops (1969 Hollis Frampton)

A lollipop is licked in extreme closeup, then from the other angle. We give a guy a lot of free passes on stuff like this when the guy also made Zorns Lemma. Halfway through it switches to first-person basketball dribbling, in approx. the same rhythm as the licking. The title refers to strong glass beads formed by dropping (dribbling?) molten glass into cold water.

–

A and B in Ontario (1984 Hollis Frampton & Joyce Wieland)

1967 home movies of these two taking home movies of each other, pausing only to reload. The game of camera warfare escapes the house and spills into the yard then all through town, hiding behind cars and lampposts, then to a park by the water. Casual back-and-forth editing until the last couple minutes when it takes some big swinging camera moves and shatters them into each other. Interesting edit overall, since you’re watching someone filming then cutting to their POV but usually/always at a different time, not to the reverse angle you’d expect.

–

From Soup to Nuts (1928 Edgar Kennedy)

In Laurel & Hardy’s first couple minutes on the job they ruin a meal, attack the chef, and break a pile of plates. Long sidetrack of the hostess attempting to eat a cherry atop her fruit cocktail, lot of cake-smashing and banana peel-slipping. Finally they’re straight-up punching their boss.

The hostess is L&H/Charley Chase regular Anita Garvin, her tall husband was featured in Modern Times. The tail end of silent comedy, fun music with sfx on the DVD. Appreciate that the traveling camera following the hostess’s wiggly ass is repeated to follow Stan when he comes out to serve (“undressed”) salad in his underwear.

–

Nocturne (2006 Peter Tscherkassky)

More classic film destruction for The Mozart Minute project, this time scenes of a masked ball and a girl escaping out her window, the Mozart soundtrack creatively degraded to match the picture.

–

Parallel Space Inter-View (1992 Peter Tscherkassky)

Not conveyable with screenshots since it’s a flicker film, alternating frames between parallel spaces. Intertitles are typed live onto a Mac word processor, like the closing credits of my own Godzilla 2. Good soundtrack, ambient noise loops. Halfway in, we get our classic narrative film footage quota, silent and strobed into some psychotronic nude woman.

–

Hotel des Invalides (1951 Georges Franju)

Fanciful little doc focusing on a war museum within the grand veterans hospital in Paris, made a couple years after Blood of the Beasts.

They saved Napoleon’s dog:

–

In Order Not to Be Here (2002 Deborah Stratman)

Opens with refilmed video of a police arrest, proceeds to a glaring spelling error in the title text, and we’re not starting out promisingly. The rest is good, a narration-free video essay on fences, walls, gated communities, surveillance – commerce centers at night. Halfway through the police presence returns, culminating in an epic chase, all (per the credits) staged.

–

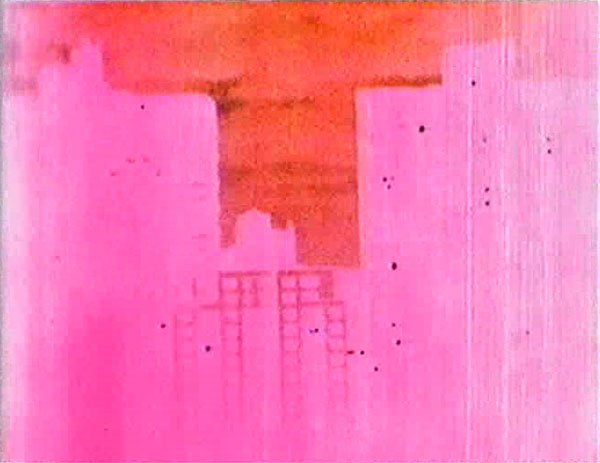

Pitcher of Colored Light (2007 Robert Beavers)

Everyday backyard light and shadow, cutting every couple seconds. Like if Portrait of Ga had fewer life details and was five times as long. This one is rare, anyway. The short that convinced me to stop watching shorts. Anachronistic, that timeless 16mm color makes it feel like the 60s or 70s, you would never guess 2007.

The titular pitcher: