Michel Simon (returning from Le Chienne) is Boudu, a crazily bearded homeless guy who grows despondent over the disappearance of his dog and jumps into the river. Hundreds gather to gawk, but one man, a bookseller who was watching Boudu before he jumped, leaps in to save him. The bookseller (Charles Granval of some Duvivier films) is congratulated and given awards for taking the poor man in, so he can’t throw him back out, even though Boudu is wrecking his house and interfering in the bookseller’s affair with his housekeeper Anne Marie. Finally Boudu wins the lottery (!), and so marries lovely Anne Marie, but just after the wedding, floating down the river with the whole family, Boudu topples their canoe and floats away, happily returning to his hobo life.

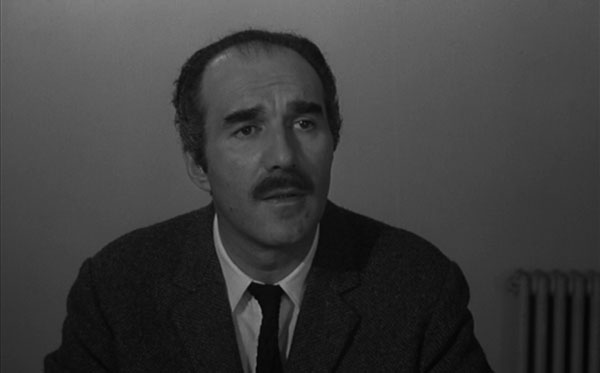

Simon at his most Charles Laughtonesque:

I can’t figure out if it’s an attack on bourgeois society, or simply an attack on everything. It opens with a couple of telling scenes. Boudu loses his dog, asks the police for help and they tell him to fuck off. A rich woman loses her dog a few minutes later and everyone in the park takes up searching for it. Then a fancy man drives up and Boudu opens the door for him. The man searches all his pockets for cash to give in return, until finally Boudu is tired of waiting and gives the guy five bucks. It’s a very fun comedy, much lighter than La Chienne and with an exuberant performance by Simon. Richard Brody calls Boudu a “walking principle of anarchy, insolence, and truth,” who “punctures the pretenses of decent society with the riotousness of a fifth Marx brother.”

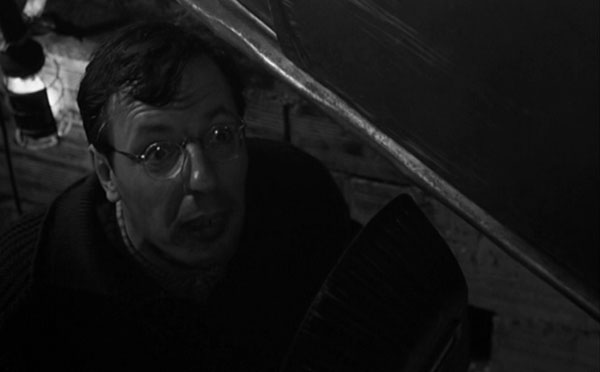

There’s a scene with Jean Daste as a student visiting the book store, and immediately afterwards, a shot of barges on the river. I figured Daste + Michel Simon + barges = a L’Atalante reference, not realizing that this movie was released two years earlier.

Jean Daste with Charles Granval:

Renoir: “The success surpassed all hopes. The public reacted with a blend of laughter and fury.”

Based on a play, which was remade for television in the 70’s, again in the 80’s with Nick Nolte then in 2005 with Gerard Depardieu.

It could be fun to think of this movie as a sequel, since Michel Simon ended Le Chienne as a cheerful hobo, his former life and marriage in tatters. But the accountant of Le Chienne was too mild to turn into a Boudu. Also, his beard wasn’t nearly awesome enough.

C. Faulkner

This is the period of the Depression in France, which accounts for the indifferent remark by a working-class character on the bridge that, of late, people have been throwing themselves into the Seine with regularity.

…

There is a sense that Boudu exteriorizes something that is in Lestingois himself, that the bookseller has summoned him up from the dark reaches of the personal and social unconscious. Boudu is everything at the center of the self and within society that has been discarded, ignored, or repressed. This “boudu” belongs to filth, to waste, to the unassimilable; he is an instinct, an urge, a drive. (What kind of name is Boudu? Does it connote a substance? An action? A disposition?) This “boudu” is something “savage” (so says Madame Lestingois), summoned involuntarily, that both attracts and repels, in equal measure, and over which Lestingois has no control, as the balance of the film proves.

Assistant director Jacques Becker plays a ranting poet in the park: