Diary of a Chambermaid (1946, Jean Renoir)

New maid Paulette Goddard (Modern Times) gets off on the wrong foot with mistress Judith Anderson (a chambermaid herself in Rebecca) by joking with the bearded master (Reginald Owen, the 1938 Scrooge), not realizing who he is. She meets desperate maid Louise, cook Marianne, and asshole valet Joseph, and gets to work. But this place is annoying and creepy: the valet (Francis Lederer, who started out in Pandora’s Box) is after her, the mistress is dressing her up for a visit from long-lost son George (sickly, secretive Dorian Gray), and the next door neighbor (Goddard’s husband Burgess Meredith) keeps breaking the family’s windows and eating their flowers. She announces she’s quitting and the valet goes mad, announces that he’s stealing the family’s treasures, then robs and murders the neighbor while the police are having their annual parade. Weird that I’d follow up Murder a la Mod with another movie that opens with a diary and features icepick murders.

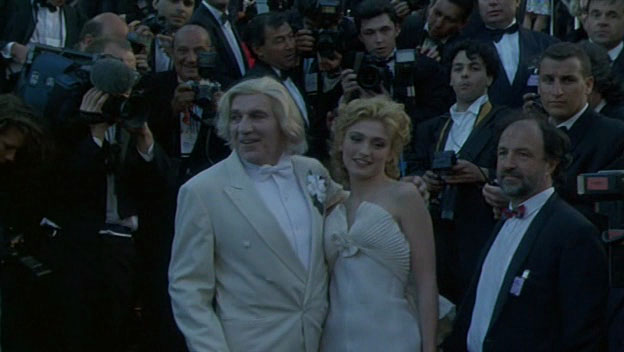

Paulette, Burgess, and squirrel:

–

Diary of a Chambermaid (1964, Luis Buñuel)

The French director had made an American film, then the Spanish director makes a French one. Now the maid is less headstrong, and has been hired to care for Madame’s dad, who wants to grab her leg while she wears special boots and reads to him. For Buñuel’s whole career everyone blabbered about surrealism, while he just wanted to put women’s legs on the big screen.

Everything is darker and more explicit in this version – Master Piccoli is allowed to sleep with the maids as long as he doesn’t get them pregnant, and Valet Joseph wants to open a Cherbourg cafe and pimp out the maid to soldiers. The valet is still a celebrated bird torturer, also a racist activist, whose 1934 “down with the republic” march gets the movie’s final words (while Renoir’s parade featured “vive la republique” fireworks). Instead of robbing the neighbor, he rapes and kills a local girl, the same day the old man dies. The maid works on helping the cops convict Joseph (and fails), but there’s no son to swoop in and save her from these awful men, so she ends up marrying the neighbor – no escape, no justice.

Madame in her laboratory:

Unlike the Renoir this one has no pet squirrel, but we do see a mouse, a frog, ants, a boar, a rabbit, a basket of snails. Supposedly Buñuel’s only anamorphic widescreen movie – maybe he regretted its mind-warping effect whenever he moved the camera. Starring Jeanne Moreau the year after Bay of Angels, and Master Piccoli after Contempt… Valet Joseph is also in A Quiet Place in the Country, Madame in Chabrol’s Bluebeard. Watched these on oscar night… they won no oscars, but Moreau got best actress at Karlovy Vary.

The Mirbeau novel was adapted again in France with Lea Seydoux, but directed by a notorious pedophile, so it’s both tempting and not tempting to watch. The book has the girl’s (not the neighbor’s) murder and Joseph stealing the family silver, then unlike both of these movies, the maid marries him and moves to Cherbourg. Randall Conrad in Film Quarterly compares the films, championing the Bunuel over the Renoir (which has no eroticism and a “deficiency in conception”):

At the least, Celestine is a moral witness to the bestiality of Joseph, something she tried to stop and couldn’t. But perhaps her secret attraction, her fear of it, and her individual powerlessness make her an accomplice to Joseph’s rise. In that case, Joseph’s assertion – “You and I are alike, in our souls” – takes on full meaning … [Buñuel] returned in his film to the France he left in the thirties, and created its portrait … The film has the closed structure characteristic of Buñuel: the end is a beginning. An individual’s gesture toward freedom not only fails but lays the ground for still worse oppression. The era that has begun, as the [fascist] demonstrators turn the corner and march up a street in Cherbourg, is the one we are still living in.