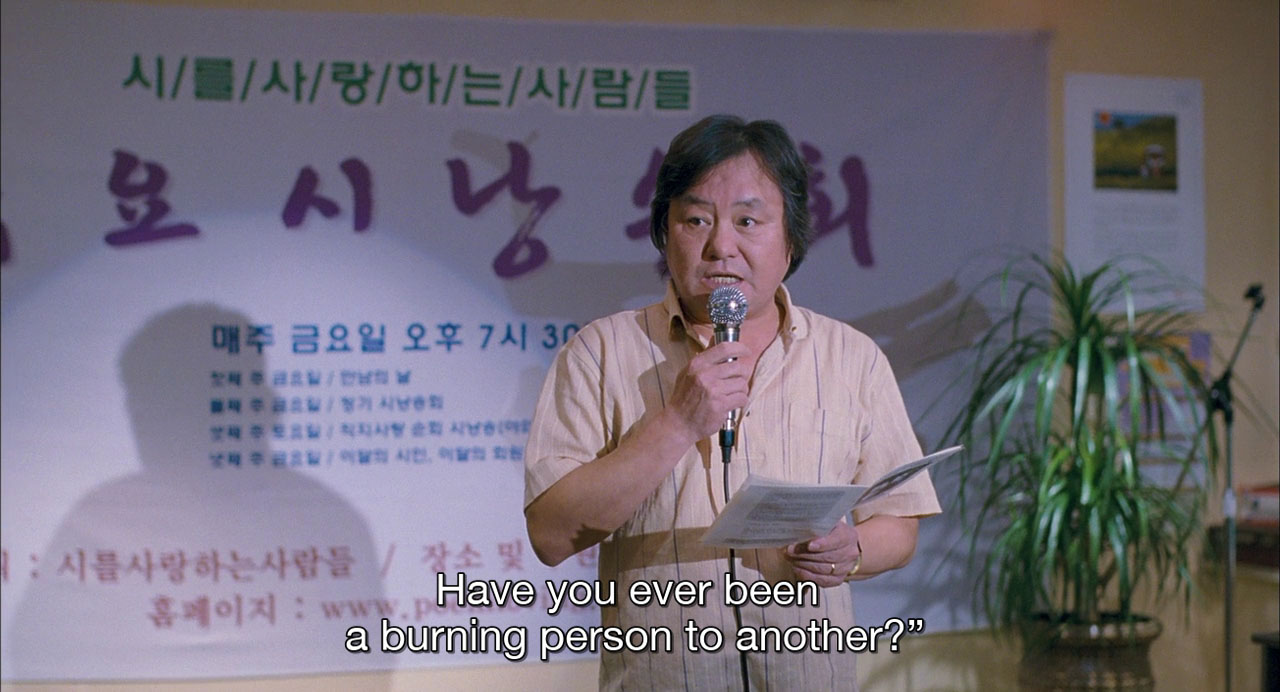

Grandma (major 60s/70s actress Yoon Jeong-hee) takes care of grandson Wook, whose friend group raped a classmate until she suicided. She tries to get enough cash from the rich disabled guy she attends for the payoff to the dead girl’s mom. Her Alzheimer’s diagnosis adds to her inner struggle but doesn’t affect the plot. When she visits the dead girl’s mom but talks only of apricots is it because the disease made her forget her reason for coming there, or was she distracted by the poetry or nature, or is she avoiding hard conversations. I have no qualms with her fellow poets but the employers, the fathers, the kids – most people in the movie are living comfortably, contemptibly.

I spend at least an hour a day saying this:

Robert Koehler in Cinema Scope 43:

There is no simple cause and effect between the initially cautious [Alzheimer’s] diagnosis and her decision to sign up for a poetry class … That doesn’t mean, however, that the viewer is denied such a cause-and-effect reading if they choose one, and Lee isn’t a filmmaker to either encourage or discourage it. This is perhaps the most notable aspect of the evolution of Lee’s screenwriting – rewarded at Cannes with the screenplay prize – starting from the unmistakable determinism of Green Fish and the elegant but closed geometrics of Peppermint Candy. Like his camera, which allows viewers to make their own compositions and choices within the larger frame, his narrative approach trusts in granting characters their own lives, so much so that one gets the sense that they frequently surprise Lee himself with the choices they make.

Auteurist foreshadowing: