An avant-garde sketch comedy omnibus, eyewash color field flashes between segments. My dream is to make a new version of this that isn’t annoying to watch, divide the four hours into eight episodes, and sell it to Criterion Channel as an original series.

Snow has called it a musical comedy, a true “talking picture” in 25 episodes. Most attempts at describing it quote his press notes: “Via the eyes and ears it is a composition aimed at exciting the two halves of the brain into recognition.”

In parts, I find it intriguing; in toto, indigestible. Encyclopedias are useful things to have around, but who wants to plough through from A to Z in a single sitting?

The Episodes (incomplete):

1. guy (Snow) making bird sounds from three angles

Out-of-focus FOCUS card that seems designed to get audiences mad at the projectionist, woman speaks about Rameau on soundtrack.

Credits are read aloud – hey, Chantal is in this. So many credits, some of them fake.

6: Office ventriloquism – these are Jonas Mekas, Marlene Arvan, Harry Gant, and the voice of Tony Janneti.

7: Conversation(?) on an airplane with the camera turned sideways and gradually rotating, cutting after each line, Abbott and Costello academia. This goes on eternally but at least it’s constantly mutating, and the chapter headings (different numbers, usually with a voice announcing “four”) make me chuckle. Gradually pulls out revealing more of its artifice, the lighting, then the director’s script prompts.

8: someone’s hands (Snow’s) play a kitchen sink like a drum (with sink/synch sound), filling it with water to hear the pitch change.

9: A guy reads nonsense words into camera, the picture glitching on each syllable. I think it’s messing with us by dropping in some real words. He takes questions at the end.

10: Four-person table read among cacophony from different playback devices, primarily piano music by Rameau. They start talking in sync with their previously-filmed selves, sometimes their voices cut out, sometimes you have to turn down the TV volume because the cacophony gets too intense. This was Deborah Dobski, Carol Friedlander, Barry Gerson, Babette Mangolte. I didn’t skip ahead during this part, I think I might be immune to annoyance.

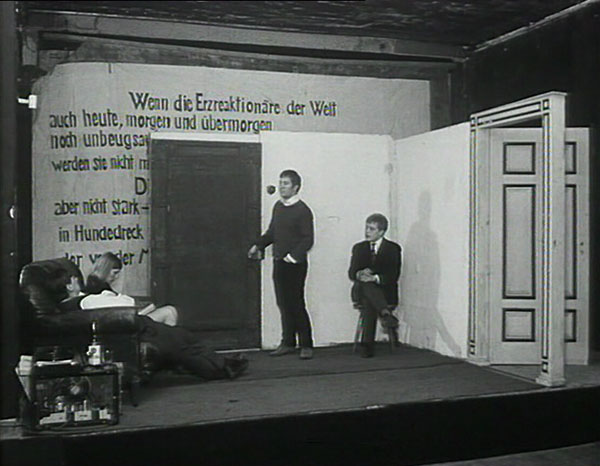

11: short one, visual of people riding a bus while voiceover talks about our man-machine future.

12: a group converses in a possibly made-up language while one of them films us watching… aha it was reverse-speak since the scene then plays backwards and flipped L-R with the sound reversed, but due to the sound quality I still can’t tell if they’re speaking English words. One of the two segments with professional actors, the other being #20.

13: A four-person sync-sound mockery in front of a museum diorama… on the soundtrack they’re reading each line all together, while on the visual one of them fake-lip-flaps a repeated pattern, until the film devolves into a stuttering flicker-horror. This one gets so loopy that it’s hard to tell if we’ve reached the between-scenes eyewash or if the scene has reached the limits of pure love and light.

14: Nude couple pissing into mic’d-up buckets, short segment.

15: Long one with a group in a fancy room, first making mouth sounds when a spotlight passes their face, then making sounds collaboratively, trying to emulate a Bob Dylan song heard on tape, lipsyncing “O Canada,” telling jokes, listening to the wall, all in the familiar stop-and-start style from the airplane segment. These are Nam June Paik, Annette Michelson, Bob Cowan, Helene Kaplan, Yoko Orimoto.

16: Hands are manipulating each item on a desk full of objects and a voice is breathlessly narrating the hands’ actions. It seems the voice is seeing what we see and trying to keep up, but then the voice catches up and gets ahead, so it seems the hands are following the voice’s instructions. The voice falls way behind again, with jumpcuts and blackouts in the image.

Short one, a family watches TV, hysterical laughter is heard, a mic faces an empty chair.

18: Girl looks out cabin window and we hear rain but don’t see any, then a rain-streaked glass is added in the foreground to complete the picture, other elements (including the girl) pop on and off. This is Joyce Wieland.

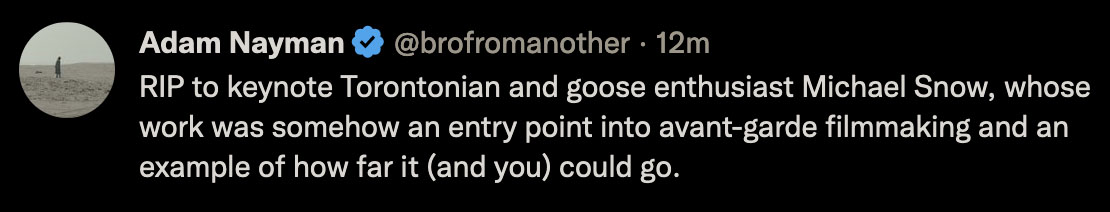

Three people sit awkwardly in a basement while a British comedy routine about religion plays on soundtrack, the picture cutting to a new lighting and pose when the radio show changes lead speaker.

20: People take turns reading lines, quick fades at end of lines to black or a color field or a strumming guitar. More setups and activity here than usual, I feel like the movie has been creating an alphabet Zorns Lemma-style and I haven’t been learning it. Settles into a one shot-per-spoken syllable rhythm, then mutates again, and again – this one has so many variations it’s like the full film in miniature.

Colored gels waved in front of a woman in bed. “Seeing is believing,” or is it? Double-exposure, a skit where some people conjure a bed (with an editing trick), then destroy a table (with a hammer). The only segment to include a hardcore sex scene, whose sound we only hear later as hands play a piano.

Bearded guy (Sitney) talking in profile, explaining that the onscreen numbers have been counting appearances of the word four/for in the movie, but the man splits into alternate versions of himself and jumbles the count.

Short scenes: empty tin/bell ring/snowy car, then credits/corrections/addenda.

from Snow’s notes:

Control of WAVES OF “COHERENCE” necessary. Rhythm continues but certain elements become more sequential then become more varied again … The entire film an “example” of the difficulty (impossibility) of the essentializing-symbolizing reduction involved in the (Platonic) nature of words in relation to experience (object) etc. discussed. The difference between the reduction absolutely necessary to discuss or even describe the experience and the experience. Each is “real” but each is different.

Regina Cornwell in Snow Seen:

Unlike the descriptive, literal, sometimes punning titles of many of Snow’s works which point to themselves, the title “Rameau’s Nephew” by Diderot (Thanx to Dennis Young) by Wilma Schoen appears to function differently. Denis Diderot, philosopher, editor of the Encyclopédie, art critic, theorist of drama as well as author of several plays and other fiction, was a major intellectual figure of the eighteenth century in France. Dennis Young receives thanks because he gave Snow the copy of Rameau’s Nephew by Diderot. Young was at that time a curator at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto. Wilma Schoen is a pseudonym: schoen the German word for beautiful, Wilma Schoen an anagram for Michael Snow. Jean Philippe Rameau was a contemporary of Bach and Handel who contributed important theoretical writings on harmony, wrote harpsicord music, operas and opera ballets. He was for a time admired by the French intellectual circle which included Diderot, Rousseau and d’Alembert. And he did have a nephew, a would-be musician and somewhat of a ne’er-do-well named Jean-François Rameau.

Sitney, who’s in the movie, calls it “the most comprehensive, and the most impressive, of the serial films of the seventies … The whole rambling film seems organized around a dizzying nexus of polarities which include picture/sound, script/performance, direction/acting, writing/speaking, and above all word/thing. The film opens with an image of the film-maker whistling into a microphone and ends with a brief shot of a snowdrift, so that the work is bracketed by a rebus for Mike … Snow.”