Musco (1997, Michael Smith & Joshua White)

A fake 1984 infomercial for a music-oriented lighting equipment company. I don’t get it. It was part of an art installation, and I don’t get those in general, maybe because I don’t live in New York.

Flash Back (1985, Pascal Aubier)

Two-minute short – soldier is killed in combat, life flashes before his eyes represented by photos going back in time until to the earliest baby picture. Guess Pascal had to find an actor with lots of family photos for this.

The Apparition (1985, Pascal Aubier)

A guy’s bathroom light makes the Virgin Mary appear in a church across town. Aubier ought to be at least as popular as Don Hertzfeldt.

Un ballo in maschera (1987, Nicolas Roeg)

Things I like:

1. That the king is played by a woman (Theresa Russell) with a mustache

2. That the action takes place in an ellipsis (“…but”) between the opening and closing text (“King Zog Shot Back!”)

Nice piece, set to music by Giuseppe Verdi. First segment of the anthology film Aria, which I must watch the rest of when I’m not so tired (next segment put me to sleep in a couple minutes).

Universal Hotel (1986, Peter Thompson)

“1980, I have a strange dream. Between the fortress and the cathedral is the universal hotel.” Slow, calm analysis of photos and reports about a nazi experiment where prisoners were frozen then revival was attempted using boiling water, microwaves and “animal heat.” “I make statements about the photographs which cannot be proven. I speak with uncertainty.” Increasingly intense, with narrated dreams illustrated with photography tricks, a murder-mystery without an ending. Last line: “they come while I’m asleep.” Scary, and I would not have watched this right now had I known nazis were involved, but now I’m glad I did.

Universal Citizen (1987, Peter Thompson)

Now in Guatemala, Peter talks with a concentration camp survivor who told himself he would move to the tropics if he survived. He did, so he does, laying in a hammock, floating in the warm water, working on the sun roof of his house, listening to Armenian records and refusing to be filmed. Mayan ruins. This time the dream/nightmare scenes lack narration. Ends with a joke (and a shot from the beginning of the other film). Oh wait, no it ends with depression after the credits. I preferred the joke.

Bunker of the Last Gunshots (1981, Jeunet et Caro)

There’s an insurrection inside the bunker. A timer count backwards, people have gas masks and eyegear and prosthetic limbs, there are shootings, eletroshock, cryogenics, there is complicated machinery, tubes and wires and hidden cameras. Possibly they are Germans, it is possibly post-apocalyptic, and the soldiers possibly go crazy and kill each other. I am not entirely sure of the politics, but it’s a neat little flick, definitely full of the clutter style of their later features.

Opening Night of Close-Up (1996, Nanni Moretti)

That’s just what it’s about. The nervous cinephile (Moretti himself) who runs an Italian theater is opening Kiarostami’s Close-Up and wants everything to be just right.

World of Glory (1991, Roy Andersson)

“This is my brother. My little brother. I suppose he is my only true friend, so to speak. [both look away uncomfortably]” I just checked and yeah, Roy Andersson is the acclaimed deadpan comedic filmmaker who made Songs from the Second Floor and You, The Living. I’d believe it, and be almost excited to see those two after viewing this short, a guy grimly introducing us to his sad life, with he and others looking slowly into the camera as if we’re to blame for all this – except why did it start with a mini-reenactment of the holocaust? The whole rest of the movie I’m wondering that… he won’t let go of the “blood of christ” wine pot at mass and it’s supposed to be a funny scene but I’m thinking “the holocaust?!?”

Reverse Shot explains:

World of Glory locates a society — ostensibly the director’s native Sweden, but easy interchangeable with any modern European country — so paralyzed by ennui, anxiety, and desperation that its inhabitants are apparitions. The main character is a thin, pasty man who takes us on a guided tour of his life — his loveless marriage, his stultifying job, his pathetic day-to-day activities. It was not until the second time I saw the film that I realized that this character had been present in the first shot: dead center of the frame, turning away from the proceedings every so often to fix us with his gaze. His meek, self-effacing misery in the later scenes thus comes into sharper relief: a person who does not act to avert tragedy endures beneath its weight.

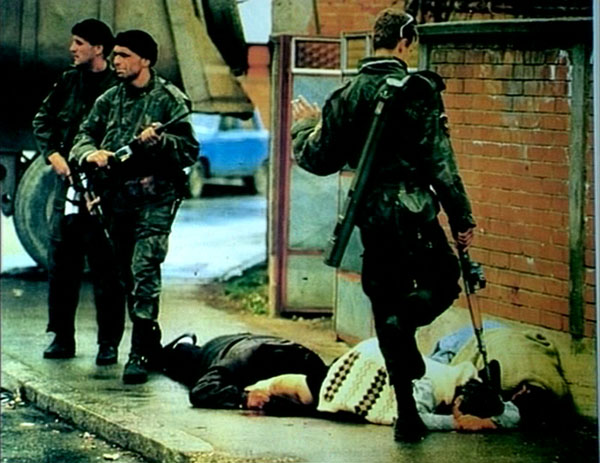

Je vous salue, Sarajevo (1993, Jean-Luc Godard)

“Culture is the rule, and art is the exception. … The rule is to want the death of the exception, so the rule for Cultural Europe is to organize the death of the art of living, which still flourishes.” This two-minute piece is a montage made from a single photograph, with voiceover. Directly to the point, I like it better than almost all of Histoire(s) du cinema.

Origins of the 21st Century (2000, Jean-Luc Godard)

A bummer of a film, montaging footage from news videos and feature films (The Shining, The Nutty Professor, Le Plaisir) over quiet music with the occasional commentary or block lettering, war and death, pain and happiness and a few plays-on-words.

If 6 was 9 (1995, Eija-Liisa Ahtila)

Sex, split-screens and supermarkets. More people looking into the camera confessionally, but all about sex this time, not too similar to Today.

Can’t figure what a full hour-long Ahtila film would be like, but she’s made two of them so I’ll find out eventually.

Zig-Zag (1980, Raul Ruiz)

Ruiz had adapted Kafka’s Penal Colony ten years earlier so surely he knows he’s making another Kafkaesque film here. A man named H. “realizes he is the victim of the worst type of nightmare: a didactic nightmare” when, late for an appointment, he finds himself part of a global board game at the mercy of pairs of dice. The game keeps changing scale, zooming out, so H. has to travel further distances more quickly – from walking to taxi to train to plane. Rosenbaum (who says it’s Borgesian not Kafkaesque) says it was made to promote a map exhibition in Paris, which to me just makes it more strange than if it was promoting nothing at all. “The history of cartography [is] the business of labyrinth destruction.”

Either H. or the mysterious gamer was played by Pascal Bonitzer, cowriter of some of Rivette’s best films. “We now live in the pure instantaneous future.”