Firstly, the “Ceddo” are the outsider townspeople. Took me half the movie to figure that one out. The town is converting to muslim, and the local imam is becoming more powerful than the king. A small group of traditionalist men kidnap the princess to protest the forced religious conversion. Meanwhile, a white christian missionary is looking for followers but is not doing so well.

While the king and imam disagree over how to proceed and the imam’s men plot to overthrow the throne, three younger men – the king’s potential successors and the princess’s potential husbands, depending which rules you follow – aim to rescue the princess, bringing guns to a bow-and-arrow party. Biram is kind of a compromise choice between mirror-wearing king-loyalist Saxewar and committed muslim Fall, but Biram is easily killed by an arrow. Saxewar goes next, dies stabbed through the throat by the kidnapper. Fall becomes suspicious of the imam and renounces his position, and finally the imam carries through his threat of deposing the king (who dies offscreen) and has the lead kidnapper killed, freeing the princess. She marches right back into town, grabs a rifle and blows away the imam herself. Damn, Sembene was good with endings.

Much of the story revolves around slavery. A white trader is in town accepting slaves in exchange for wine and guns, so Ceddo are trading members of their own families for guns to fight the muslims. One reason people are converting to islam in the first place is because law prohibits children who are born muslim to become slaves, so if young adults convert, they might still become slaves but their children will be born free. The christian missionary has no such promise, and at most manages to collect one follower, or at least a curious onlooker to the white man’s sermon. This leads to a wonderful dream sequence, a large modern (as opposed to the no-specific-year historical period of the rest of the film) crowd is gathered as this new guy reads a memorial service for the white priest, seen in a coffin… dreams of a successor, unfulfilled, as the christian is killed unceremoniously later in the movie.

Watched this from a very good print with strong color rented from recently-folded New Yorker Films – we were warned that this may be the last screening of this particular film for a long time. This was made two years after Xala – seems that this is the turning-point film for me in Sembene’s career, since I’ve enjoyed this one and everything after it (Guelwaar, Faat Kiné, Moolaadé) more than everything before it (Xala, Emitai, Black Girl). Can’t put my finger on why I like the later ones more… better color, stronger characters, easier-to-follow narratives? I don’t know why I like movies, but this one was damn amazing. We’ll see how unseen early film Mandabi and late Camp de Thiaroye hold up.

The princess appeared 20+ years later in Faat Kiné, and Prince Biram played an interpreter in Coup de torchon

We were always looking for the camera’s reflection in Saxewar’s mirror:

From the valuable article by J. Leahy at Senses of Cinema:

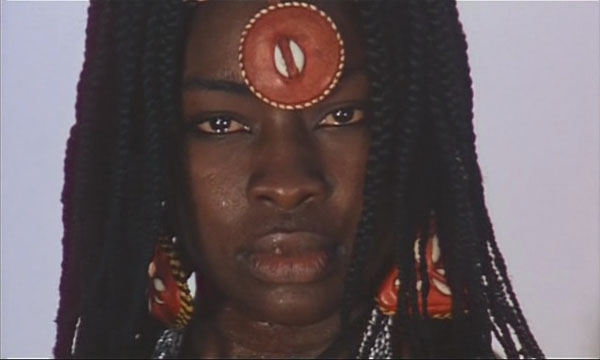

Sembène goes so far as to articulate something completely ignored in the discourse of the male protagonists of the village’s internal war: the desire of this strong, silent, beautiful young woman. This is revealed in what I read as a subjective flashforward to a possible future, similar to that of the priest. It is characteristic of the complexity of Sembène’s analysis of the interaction between the individual, history and traditional practice that this shows her married to her kidnapper and finding happiness in the role of a traditional wife serving her husband. Others have read this as flashback to their first encounter. Even if this is so, the moment remains equally evocative in terms of the possibilities it suggests.