Finally I got a chance to watch this, said by some to be Rivette’s finest hour (errr, four hours). I can’t say I agree, but I came in with absurdly high expectations, and having seen nearly all of Rivette’s other films. So its endless theater rehearsal scenes held no surprises, but the movie perked up considerably in the last hour. As usual, I’m feeling more strongly about the film after reading a hundred online articles about it. And unlike in Gang of Four, I actually picked up on some connections between the theater-rehearsal dialogue and the actors’ lives.

Claire (Bulle Ogier in her first Rivette film) lives with boyfriend Sebastien (Jean-Pierre Kalfon, a lead in Love on the Ground). Sebastien is directing a play – Racine’s Andromaque (it’s always some ancient text), which Bulle quits at the start of the film (I think right near the beginning of rehearsals), spending the rest of the movie at home not wanting to do much of anything.

The play rehearsals are being filmed in 16mm for a documentary about the theatrical process – by director Andre Labarthe (a Cahiers critic turned Cineastes/Cinema de notre temps director) and cameraman Etienne Becker (Jacques’s son, he shot Phantom India and parts of Le Joli Mai), playing themselves. So the actors in the film are playing actors in a play, interviewed in character by Labarthe. And Becker’s footage of the play rehearsals is edited into the film proper (which is mainly shot in 35mm by Alain Levent, cinematographer of The Nun).

The amour of the title is between Claire and Sebastien, though it doesn’t seem that way until the three hour mark, at which point Sebastian’s frustrated love life and his play rehearsals have been at a standstill for so long, one of them has to explode. So he takes a few days off from the theater, goes home, and he and Claire get naked and fou, finally tearing through the wall of their apartment to have sex at their neighbor’s place.

Other interesting bits: the play and documentary directors get dinner together and talk about Jerry Lewis. The nature of the sound changes when the movie switches cameras from 35 to the 16mm documentary, but both feature loud, clompy footsteps on the wooden stage. Sebastian’s awful clothes always clash with his awful wallpaper.

Movie takes place over two and a half weeks – title cards display the date. Before the first card, some shots (which make no sense at the time) show Claire on the train, and the wrecked apartment. Claire walks out of the play on the 14th. On the 17th the documentary crew interviews Claire’s replacement Marta (Sebastian’s ex-girlfriend, whom he tries to sleep with again) and Claire starts following Sebastian through the streets after rehearsals.

The 19th: Sebastian is interviewed about playing Pyrrhus himself while directing the play. He sleeps at the theater, gets a call saying Claire tried to kill herself. He returns home, bringing her a record with a dog on the cover. 22nd: She goes looking for an Artesian Basset like the one on the cover, almost steals one from a guy.

24th: Claire in full spy mode, watching out her window and reporting everything into a tape recorder. A weird moment, a shot of two chairs going in and out of focus. Claire invites Marta over, tells Sebastian she wants a divorce, and hooks up with her ex Philippe. The first real crazy scene (if you don’t count the chairs): when she says she’s leaving, Sebastian wordlessly starts cutting up all his clothes.

26th: Claire is back with Philippe, someone at the theater tells Sebastian that rehearsals are becoming impossible. He goes home. 28th: full-on fou. Seb and Claire draw all over then destroy their wallpaper, chop through a wall and make love everywhere, until she suddenly says she’s tired and that he needs to leave. He goes to the theater.

31st: Claire is cutting herself, he tells her to stay. 1st: She is free, has a friend call Seb from the train station to tell him that she’s left. “I feel like I’ve suddenly woken up.”

The movie gets more complicated when you read about its production. Sure, Rivette is directing a feature fiction film, but it’s based largely on improvisation – plus Jean-Pierre Kalfon is really directing the Racine play. He even cast the actors. One of them is Francoise Godde, who played a domestic maid in The Nun. Also in there somewhere is Michel Delahaye, “the ethnologist” in Out 1. Michele Moretti (Out 1‘s Lili, leader of the Thebes theater group) plays (or IS) Kalfon’s assistant on the play. And the documentary filmmakers are doing their thing independent of Rivette’s feature, getting in close and conducting their own interviews while the 35mm camera stays distant and unobtrusive.

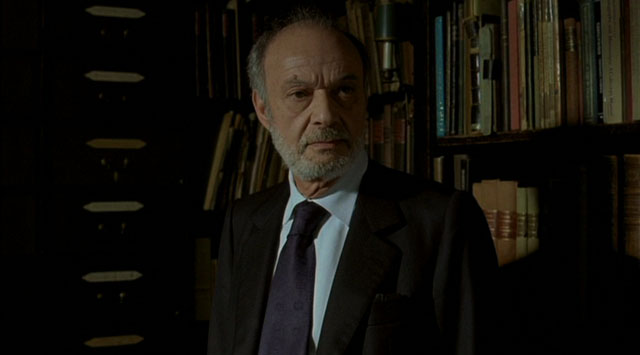

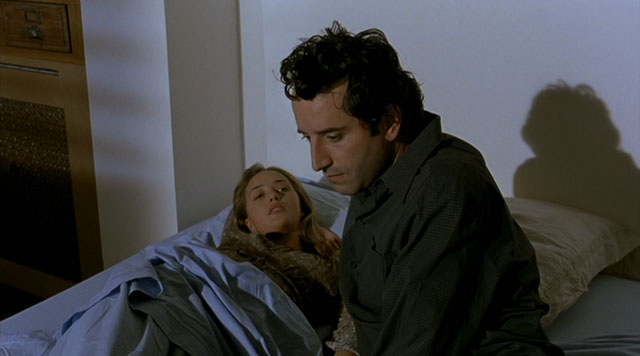

16mm:

35mm:

According to a Greek mythology site, the play is from 1667 – “The structure of Racine’s play is an unrequited love chain,” and it’s “the most often read and studied classicist play in French schools.”

Shooting Down Pictures – who gets credit for getting there first, and linking me to a bunch of articles from which we quoted the same things:

Sebastien, made self-conscious of his directing technique after watching rushes of the doc, adopts an increasingly hands-off approach to the production, effectively casting the production adrift in endless rehearsals without a clear sense of focus. … [the film] seems implicitly to be an inquiry on the limits of what straight shooting of spaces and interactions can tell us.

Director’s assistant Michele Moretti and a tired-looking actress:

Rosenbaum:

The rehearsals, filmed by Rivette (in 35 millimeter) and by TV documentarist Andre S. Labarthe (in 16), are real, and the relationship between Kalfon and Ogier is fictional, but this only begins to describe the powerful interfacing of life and art that takes place over the film’s hypnotic, epic unfolding. In the rehearsal space Rivette cuts frequently between the 35- and 16-millimeter footage, juxtaposing two kinds of documentary reality; in the couple’s apartment, filmed only in 35, the oscillation between love and madness, passion and mistrust, builds to several terrifying and awesome climaxes in which the distinctions between life and theater, reality and fiction, become virtually irrelevant.

He also says the movie may have been inspired by the “psychotic breakup” of Godard and Anna Karina.

K. Uhlich:

The result is a mish-mash of ideas and situations both brilliant and inane: a good stateside comparison, coincidentally created around the same time, is John Cassavetes’s Faces, which, like L’Amour Fou, is a jagged-edge black-and-white psychodrama prone to rather unbelievably grand gestures in constrictively intimate settings.

Peter Harcourt:

The films ends with the same shots that had opened it, with the sense of separation and emptiness — Claire travelling away on a train; Sebastien as if defeated, in his apartment; the characters of the play, in costume and make-up, as if ready for a performance; and then that slow tilt down from those few spectators in that huge arena onto an empty stage as we hear, as if from some other space, a baby crying — as we had heard as well at the opening of the film.

Mirror-mirror

Rivette 1975:

Shooting a film should always be a form of play, something that might be seen as a drug or as a game. Even during the ‘breakdown’ scenes near the end of L’Amour fou I was not being tragic as many people thought. I was joking, having fun, and so was Bulle. It’s just a movie, not some kind of cinéma-vérité!

Rivette from an epic, essential interview for Cahiers in 1968:

I hadn’t forgiven myself for the way I had shown the theatre in Paris nous appartient, which I find too picturesque, too much seen from the outside, based on cliches. The work I had done on La Religieuse at the Studio des Champs-Elysees had given me the feeling that work in the theatre was different, more secret, more mysterious, with deeper relationships between people who are caught up in this work, a relationship of accomplices. It’s always very exciting and very effective to film someone at work, someone who is making something; and work in the theatre is easier to film than the work of a writer or a musician.

…

The film itself is only the residue, where I hope something remains. What was exciting was creating a reality which began to have an existence of its own, independently of whether it was being filmed or not, then to treat it as an event that you’re doing a documentary on, keeping only certain aspects of it, from certain points of view, according to chance or to your ideas, because, by definition, the event always overwhelms in every respect the story or the report one can make out of it.

…

I didn’t feel I had the strength, or even the desire, to make a film where the woman would really be mad. So this would only be a crisis, a bad patch, as everyone has. And that’s when it became clear that she would be no more mad than he was and even that of the two he was clearly the one who was more sick. The main feeling was also expressed in a sentence from Pirandello that I happened to find when I was reading a bit before starting to write anything at all, which I had even copied out at the beginning of the scenario: ‘I have thought about it and we are all mad.’ It’s what people commonly say, but the beauty is precisely in stopping to think about it.

…

I believe more and more that the role of the cinema is to destroy myths, to demobilize, to be pessimistic. Its role is to take people out of their cocoons and to plunge them into horror. … More and more, I tend to divide films into two sorts: those that are comfortable and those that aren’t. The former are all vile and the others positive to a greater or lesser degree.

With its four-hour length (Rivette called it “only a little longer than Gone with the Wind, though without the bonus of the Civil War”), it was a flop for producer Georges de Beauregard, who made some fifteen movies I’ve heard of before L’Amour Fou and only one after. The producers butchered together a two-hour version, which Rivette wants nothing to do with. He once spoke of making a finished edit of the 16mm documentary. But it makes sense that the documentary was never finished, just as the play was never produced – he’s more interested in the process than the finished work (see also La Belle Noiseuse).

This was the same year as Army of Shadows, My Night at Maud’s, The Swimming Pool, The Milky Way, at least two by Chabrol, Z, and Bresson’s Une Femme Douce.

B. Kite on the ending:

Sebastien, meanwhile, has learned the perils of true collaboration. Having initiated a process which assumed its own momentum, he now finds himself trapped inside it, inhabiting the shell of a departed life. Mourning is its own paranoia, and Sebastien is left locked in Claire’s old role, shut up in the apartment, listening to the recordings she had made to summarize the findings of her investigation, conducting his own investigation into absence and loss.

P. Lloyd:

The ghosts of Hitchcock, Lang and Preminger, which have haunted the New French Cinema for the last ten, years, have finally been laid to rest, by L’Amour Fou. The classical tradition has outlived its uses; but Rivette rejects that tradition, paradoxically, only because he absorbed its principles, received with thanks all that it has had to offer.

From Robin Wood’s excellent article – obviously I need to get his books:

Clearly, the length of our cinema program is closely bound up with the more obvious conditions of the current phase of consumer-capitalism: alienated labor, the five-day week, the 9-5 job, the nuclear family, a norm common to all levels from employee to executive, necessitating that (weekends apart) “leisure” be packed into a 2-3 hour slot between the time the kids are put to bed and the “early night” required by the next day’s toil. Otherwise, in one of those ugly and brutal, but entirely taken-for-granted, phrases that characterize our culture, “time is money”; and if we are going to surrender four hours of our “money” to watching a spectacle, we must be repeatedly reassured that the spectacle we are buying was extremely expensive, that we are purchasing a visibly valuable commodity. Rivette’s films, on the contrary, are perceptibly cheap … Nor is the length of the films validated by complexities of plot, large numbers of characters, “epic” events. What is the plot of L ‘Amour Fou? Sebastien tries to produce Andromaque; Claire goes mad. Rivette could easily have told it to us in fifteen minutes and spared us the superfluous four hours. The “unjustified” length of the films, then, represents an act of cultural transgression. The question, “Why this length?,” should immediately provoke a reciprocal one: Why the standard length? Why should we automatically expect our movies to last between 90 minutes and two hours, feel cheated if they are less and demand particular justifications if they are more?

…

We have, then, Rivette making a film of Labarthe shooting a documentary of Kalfon producing a play by Racine reinterpreting a Greek myth.

…

I know of no other film that so powerfully communicates the terror moving out of one’s ideologically constructed, socially conditioned and ratified, hence secure, position and identity, into… what? Which is precisely the question with which the film leaves one: a political question if ever there was one.

JULY 2025: Watched again in beautiful HD (some screenshots replaced). The halfway point is when the movie loses its mind, along with Bulle. After wrecking the neighbor’s place, Kalfon goes right back to work. His play only gets good when they add a percussionist in the last 20 minutes.