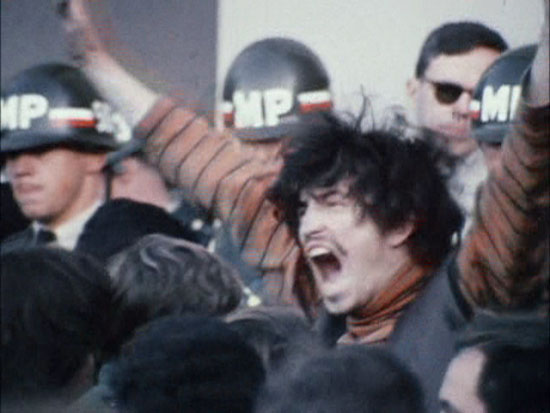

Katy and I enjoyed some oscar-nominated docs the week of the awards. This is a structurally satisfying doc about Nan Goldin’s life and art and activism through three health epidemics: the mental health crisis that took her sister, AIDS which took many of her friends, and her own opioid addiction, for which she seeks revenge through public protests to convince museums to refuse Sackler drug money.

Matthew Eng for Reverse Shot:

All the Beauty and the Bloodshed retains the impassioned clarity of Poitras’s style while enlisting its primary subject as its co-author. Goldin provides illuminating, clarifying, and always candid commentary on the many chapters of her life in one-on-one interviews with Poitras, conducted on weekends during COVID, included here under the agreement that Goldin would have final say over which of her words were included in the finished film. (She also served as a music consultant on the film, compiling an eclectic playlist that ranges from The Velvet Underground and A Taste of Honey to Lucinda Williams and The Facts of Life’s Charlotte Rae, singing the Brechtian ballad that inspired the title of Goldin’s landmark exhibition, The Ballad of Sexual Dependency.) A great deal of Poitras’s film is fittingly composed of Goldin’s work, presented to the audience in the photographer’s preferred format: the slideshow, which has long been the crux of Goldin’s practice. It is a simple yet immensely effective device—its clicks evince a pleasing tactility—that lets Goldin’s photography speak for itself and enhances the attention-seizing potency of her portraiture with its stark staging, electric colors, and magnetic characters.

Won the top prize at Venice against all the big oscar dramas (Tár, Banshees, The Whale), the arthouse faves (No Bears, Saint Omer) and the would-be contenders (Bones & All, Blonde, Bardo, White Noise). This took three editors: Amy Foote (The Work), Joe Bini (Grizzly Man), Brian Kates (Killing Them Softly). We skipping Risk, not in any hurry to catch up with it, so it felt like Poitras was gone for nearly a decade.