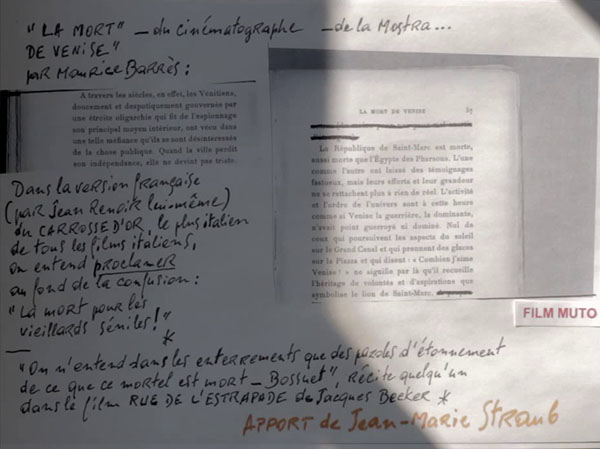

The Bridegroom, The Comedienne, and the Pimp (1968, Straub/Huillet)

Four minutes in, it’s just been a long car ride in the rain with opera music playing (there was no sound at all for the first two minutes) and I am very suspicious.

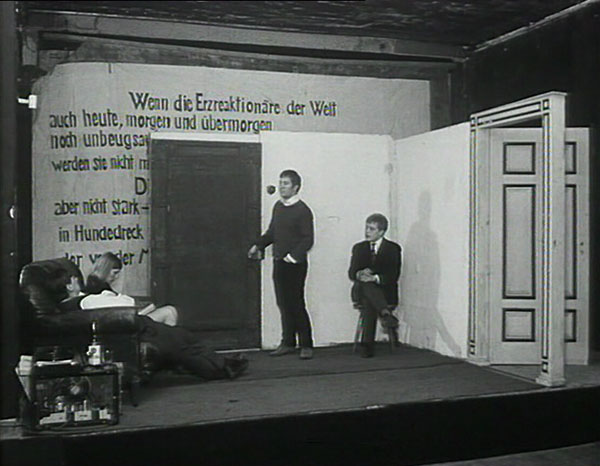

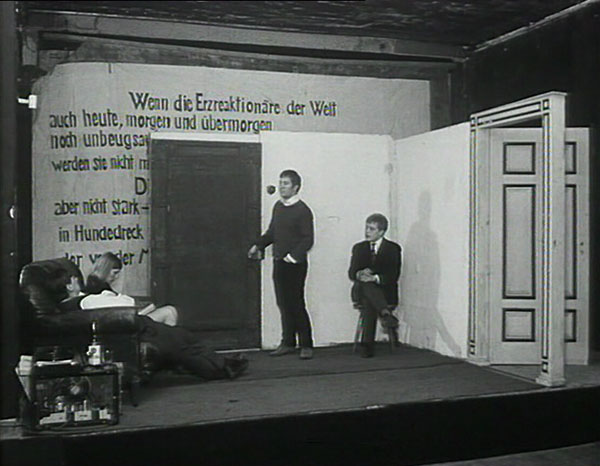

Five minutes in, cut to a stage set, with German words on the wall and a clattering wood floor. Rivette (or Michael Snow) would be pleased. A fast-paced stagey farce follows. Blackout, next scene but the camera hasn’t moved, hasn’t even cut for all I know. Actors include Fassbinder regular Irm Hermann, composer Peer Raben, and future superstar Hanna Schygulla (who I’ve recently seen in The Edge of Heaven, Werckmeister Harmonies and 101 Nights of Simon Cinema).

Bang, cut, new location, and back out on the street. An action scene. Jimmy Powell is marrying Lilith Ungerer (star of a couple Fassbinder films). They go home, the pimp (Fassbinder himself, early in his career) is there, she shoots him and gives a speech as the music returns. All affectless acting.

So, what was that all about? Well the title refers to the cinematic drama in the third section, that much is clear. And the actress and the pimp were in the stage play in the middle. IMDB fellow says “The film has its roots in a theatre production of a play by the Austrian playwright Ferdinand Bruckner which Straub had been asked to direct by a German theatre company. He considered the play too verbose and cut its length from several hours down to just ten minutes, and it is the production of this play which forms the centrepiece of the film.” As for the beginning, the same guy says it’s a “Munich street frequented by prostitutes.” F. Croce calls it a “mysterious, structuralist gag” and notes that “filmic subversion can prompt political revolution, and transcendence.” No revolution or transcendence here – I just thought it was a weird little movie made by an overacademic sweater-wearing type. Was only Straub’s fourth work – let’s check out his tenth, which is half as long.

Every Revolution is a Throw of the Dice (1977, Straub/Huillet)

It’s in French this time. Actors sit in a half-circle near the memorial site for the Commune members and recite a poem. I’m mistrustful of the English subtitle translation of the poem, and there’s not much in the movie besides the poem (the recitants are as expressionless as in the previous film, maybe even more so), so there’s not much of value for me here. Actors include Huillet herself, Michel Delahaye (the ethnologist in Out 1) and Marilù Parolini (writer of Duelle, Noroit, Love on the Ground), shot by William Lubtchansky and dedicated (in part) to Jacques Rivette.

Mongoloid (1977, Bruce Conner)

Music video for a Devo song using (I’m assuming) all found footage (science films, TV ads and the like).

Mea Culpa (1981, Bruce Conner)

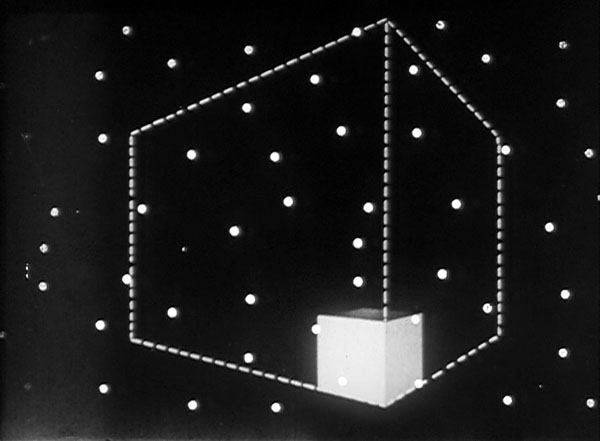

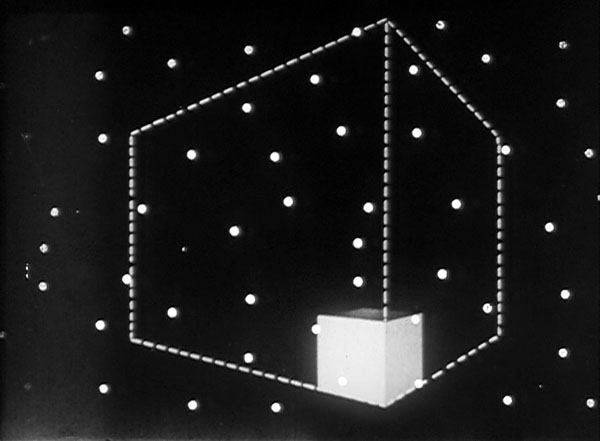

Dots, cubes, light fields and… whatever this is. Conner goes abstract! The music sounds like 1981’s version of the future. Aha, it’s Byrne and Eno, so it WAS the future. I didn’t know that Conner died last year, did I?

(nostalgia) (1971, Hollis Frampton)

of a photo of a man blowing smoke rings:

“Looking at the photography recently it reminded me, unaccountably, of a photograph of another artist squirting water out of his mouth, which is undoubtedly art. Blowing smoke rings seems more of a craft. Ordinarily, only opera singers make art with their mouths.”

So far I really like Hollis Frampton. His Lemon and Zorns Lemma were brilliant, and now (nostalgia) is too. Anyway this is the one where Frampton films a photograph being slowly destroyed on an electric burner while Michael Snow reads narration describing the next photograph that we’ll see. It’s important to know that Snow is the uncredited narrator for a humorous bit in the middle. The movie also has a funny twist ending that I wasn’t expecting. This would be part one of Frampton’s seven-part Hapax Legomena series. I have the strange urge to remake it using photographs of my own, but I lack an electric burner and a film/video camera.

Gloria (1979, Hollis Frampton)

Remembrance of a grandmother, Frampton-style, meaning annoyingly hard to watch and strictly organized. Clip from an ancient silent film, then sixteen facts about gramma (“3. That she kept pigs in the house, but never more than one at a time. Each such pig wore a green baize tinker’s cap.”) then a too-long bagpipe song over an ugly pea-green screen, and the rest of the silent film. Or as a smartypants would put it, he “juxtaposes nineteenth-century concerns with contemporary forms through the interfacing of a work of early cinema with a videographic display of textual material.” I prefer my version.

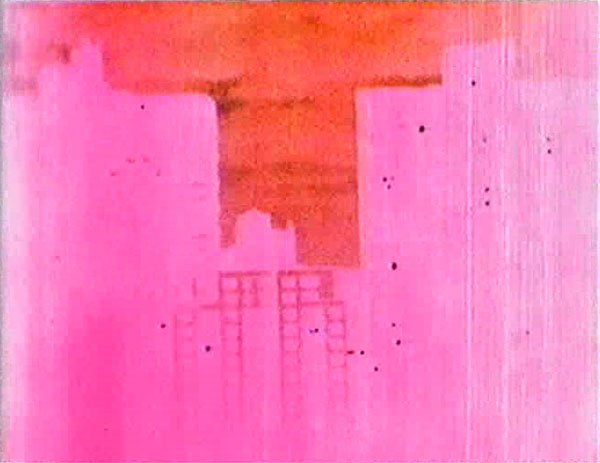

Prelude #1 (1996, Stan Brakhage)

I don’t think that I enjoy watching low-res faded videos of Brakhage movies. I’ll wait for the next DVD set to come out (or the next Film Love screening). As a side note, I cannot believe that Raitre plays stuff like this. Just imagine: art on television. Picture a single TV station anywhere devoted to showing art. Can you? Can you?!? I feel like screaming!!

NYC (1976, Jeff Scher)

Shots of the city sped-up, rapidly edited, reverse printed and hand colored, two minutes long with a jazzy tune underneath. Super, and short enough to watch twice (so I watched it twice).

Milk of Amnesia (1992, Jeff Scher)

I’m thinking it’s short scenes from film and television, rotoscoped, with every frame drawn in different colors, with some frames drawn on non-white paper (a postcard, some newspaper). Warren Sonbert is thanked in the credits. I would also like to thank Warren Sonbert.

Yours (1997, Jeff Scher)

An obscure musical short from the 30’s or 40’s overlaid with rapidly-changing patterns and images from advertisements. Descriptions and screenshots can do these no justice.

Frame (2002, n:ja)

Black and white linear geometry illustrating a Radian song. I can’t tell if it’s torn up by interlacing effects or it’s supposed to look that way. Give me Autechre’s Gantz Graf over this any day. Between this and Mongoloid and the Jeff Scher shorts, I’m not sure where to draw the line between short-film and music-video. Not that it’s a dreadfully important question, but I’m in enough trouble tracking all the films I have/haven’t seen without adding every music video by every band I like onto the list. Although maybe videos should be given more credit… I’m sure Chris Cunningham’s video for Squarepusher’s Come On My Selector would beat 90% of the movies I watched that year.