Up to the Expressionism chapter in the Vogel. Our Lady of the Turks was a bust, and I had Viva La Muerte lined up but it sounds depressing, so I’m turning to shorts: three from Expressionism then three from Surrealism.

–

The Reality of Karel Appel (1962, Jan Vrijman)

The artist looks like he is fencing with the painting, and the camera. Short doc portraits of artists aren’t usually the most creative, so I was surprised to see that Vogel picked a few. This is really good, with a jazz montage of Appel cruising a junkyard, and crashing sfx as he attacks a canvas. Appel contributed his own music.

–

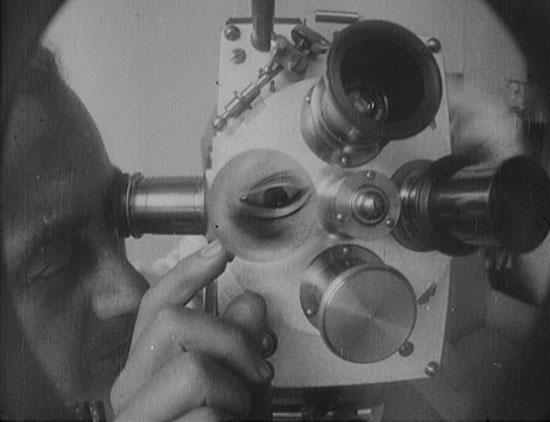

Visual Training (1969, Frans Zwartjes)

Stonefaced blackeyed man eats his jam and toast in a bowl, then smears his breakfast all over a nude woman on the table. There’s lots of posing, and looking into the camera. Sounds like a Kurt Kren actionist short, but unlike Kren’s, this one is actually good. No audio, I played the opening track to Zorn’s Heaven & Earth Magick. Zwartjes made about thirty more films, and if they’re available somewhere I’d consider a marathon.

–

The Liberation of Mannique Mechanique (1967, Steven Arnold)

Another short with heavily made-up topless women, this time with less posing, the actors and camera in constant movement. Good use is made of feathers and a glass table, multiple takes of the same scene are strung together. Some pretty-whatever music, I should’ve kept playing Zorn. Debut short of Arnold, a Dalà associate.

–

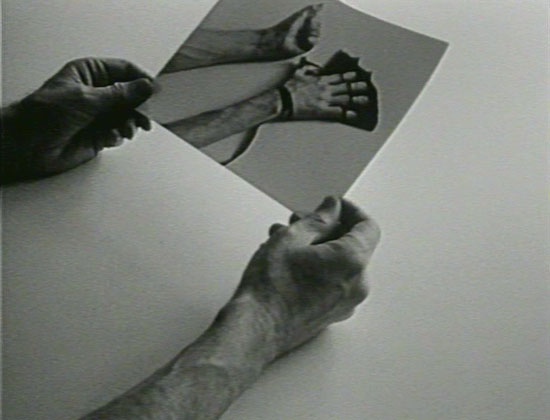

Magritte: The Object Lesson (1960, Luc de Heusch)

Cutouts of the paintings fade into each other. I barely know Magritte’s name but I know some of these images – “This Is Not a Pipe” and the hatted man facing away from us. He painted more birds than I realized. Vogel: “one of the few films to deal with the philosophical basis of contemporary art,” true enough. De Heusch worked with Storck, and previous to this he made a film about eating, which would’ve also fit into this program.

–

Eaten Horizons (1950, Wilhelm Freddie & Jorgen Roos)

Weirdo little short with abrupt picture and sound editing, fetishizing loaves of bread. A woman is opened up so her insides can be eaten, a loaf is cut and bleeds goopy guts. Freddie provides the art-world weirdness here, Roos (who’d just made a Cocteau doc) the cinema experience.

–

The World of Paul Delvaux (1946, Henri Storck)

Forming a trilogy of short docs about painters. I didn’t dig the music or the dramatic poetry reading, but it’s cool to zoom in and around the paintings, lingering on background details. This one’s all paintings – unlike the other two, the artist doesn’t appear in person. Vogel: “Storck’s outstanding work extends from early radical documentaries to later surrealist films.” He also worked with Ivens, and his other stuff looks interesting; political.