Made and released before My Night at Maud’s, but it’s part four of the Moral Tales. I made a moral decision to watch the films according to their numbering in the DVD box set, and not in the order they were made.

It’d be almost Antonioni-esque without the voiceover. Hardly anything actually happens, but Adrien always keeps us filled in on what he’s thinking. I considered disliking the movie for a while, a movie about idle rich young artists having self-conscious affairs, but it turns out Adrien and Haydée aren’t rich (only idle and leeching off their rich friend) and never manage to have an affair. I ended up liking it.

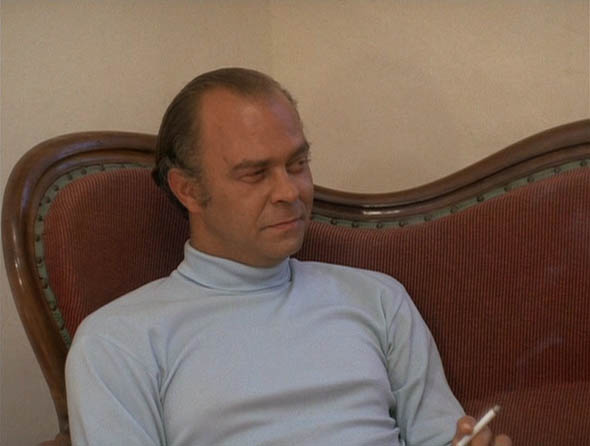

Buff 30ish Adrien comes to the beach to take his “first vacation in ten years” prior to an art opening, hopes to sit around with buddy Daniel and do absolutely nothing, not even think (they read so they don’t have to think). 21-yr-old Haydée is also at the house sleeping with a different guy every night. We don’t get much insight into Daniel – he’s the third wheel here – but Adrien and Haydée are both trying to find themselves, define their own moral codes, playing off each other and never quite getting together. At the end, Adrien pulls a standard Moral Tales move. Chances are good that he’s got Haydée for the night, but he leaves her in the middle of the road, deciding that sleeping with her would be against his character, and books a flight for London to see the girl he’s with (briefly) at the start of the film.

Leisurely-paced movie, but never slow or dull. Differently structured than the other films, with a few-minute prologue for each character before the main section of the movie begins. Rohmer and his cameraman would be happy to just stare at Haydée all day – her entire prologue is shots of her barely-clad body. Apparently that’s what defines her character.

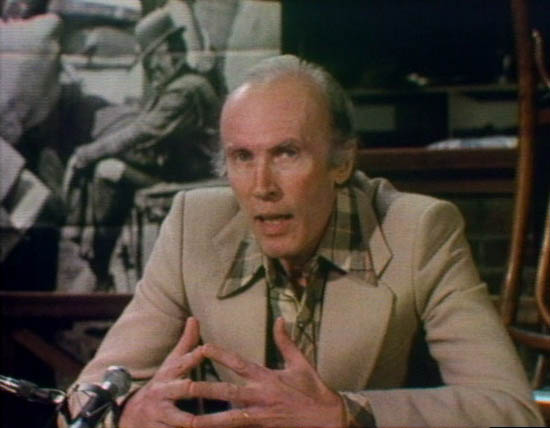

Have I mentioned that it is in color? Guess that’s another good reason to watch it fourth instead of third. Nice, rich color, too. Much of the look is in the bleached grays and browns and blues of the beach and the plain interior of their villa, so what colors we get in clothing and city life and an antique vase all stand out. Adrien and Daniel wear some hilarious clothes throughout (see above). Must be a 60’s artist thing.

Adrien was Patrick Bauchau, had a smallish part in Suzanne’s Career, later in American stuff like The Rapture and Panic Room. Haydée was Haydée Politoff, immediately turned to Spanish and Italian horror movies, had a small part in Love in the Afternoon, and mostly quit acting after that. Daniel was Daniel Pommereulle, appeared in Godard’s Weekend the same year, then two by Philippe Garrel.

from V. Canby’s NYT review:

Much of the comedy in La Collectionneuse, as in Rohmer’s later films, is provided by the otherwise aware hero’s elegant self-deceptions about his own motives, followed by his dimly seen perceptions of what could be another truth. In this context, it is a momentous event (and, comparatively speaking, momentously funny) when Adrien begins to have doubts about the affair of Haydée and Daniel. “I couldn’t be sure,” he tells himself with complete seriousness, “that their complicity was entirely for my benefit.”

There is a certain chilliness and lack of spontaneity to all of the performances, especially Bauchau’s, which, I suspect, has as much to do with the tiny scope of the film as to the actor’s talents. My Night at Maud’s and Claire’s Knee suggest living worlds outside the films’ rarefied milieus, whereas La Collectionneuse exists in splendid, arrogant isolation. Adrien is tiresome. Daniel is enigmatic, and Haydée is sweet, and great to look at, but, after a while, sadly commonplace.

A note of interest to local film buffs: the Seymour Hertzberg who is listed in the credits (he plays Sam, the American art collector whom Adrien solicits), is the nom d’écran of Eugene Archer, a former New York Times film reviewer who, I’m told, has absolutely no intention of acting again. He is an excellent reviewer.

“Seymour Hertzberg”:

From P. Lopate’s Criterion essay:

Haydée is not the most articulate young woman, though she says just enough to cast doubt on the men’s interpretations. There will be other Rohmer films that take us deep into the psyches of women; this one does not, but it gives us a very daring, precise portrait of the misogynistic, entitled, self-loathing psyches of men. And unlike, say, most Woody Allen movies, it does not let the rationalizing male character off the hook. Rohmer explicitly warned us, in an interview: “You should never think of me as an apologist for my male character, even (or especially) when he is being his own apologist. On the contrary, the men in my films are not meant to be particularly sympathetic characters.â€

From an appreciation in The Guardian:

Drama, for Rohmer, is made up of a number of frequently small incidents which culminate in an inevitable denouement. There are many kinds of film-making but Rohmer’s would be very difficult to beat within the confines of his chosen metier.

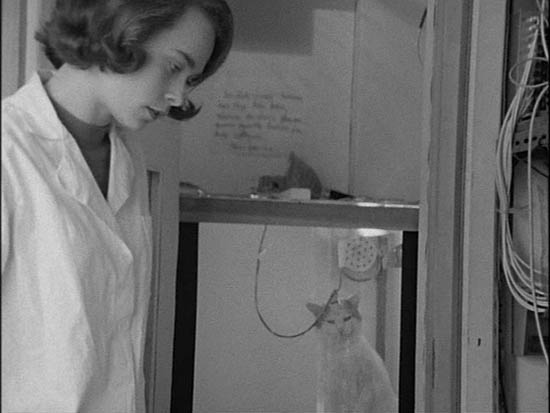

A Modern Coed, 1966

“People used to say girls went to college only to land a husband. Though today’s coed might find a husband, she isn’t necessarily looking.”

Just a short doc to tell the world that there are female college students, and some of them even study science. Its main reason to exist today is to document mid-60’s Paris hairstyles. Narrated by Vidal from Maud’s.

Foreground: our coed. Background: a cat with a hat in a box.

Rohmer on La Collectionneuse in 1977:

“It’s the only film I made that followed the era’s fashion. Audiences loved the new fashions, the long hair, the blue jeans. Then there was Haydée, whom audiences adored. Marcel Carné signed her for his next film right after that.”

He speaks proudly of a conversation scene in the 1976’s The Marquise of O, calling it “tiresome and static” but saying nobody else would have dared film it as written.

“This is a problem that concerns me. In the past, I was drawn by the way people spoke. I’m deeply interested in language. Currently, I find a kind of sloppiness has crept into the French language and I don’t like it very much. I like colloquial language, but today, especially as it’s used in intellectual circles, I find little of interest in it. … That said, I also believe characters in film should speak naturally. I’m getting around this currently by shooting films set in the past. When I return to contemporary films, I don’t know what my position will be. Perhaps by then language will have evolved further. Today’s spoken language is so extremely impoverished that it doesn’t inspire me. You find the same dialogue in every film now.”