Program kinda sucked this year. Feels like I spent enough time on it already, so not gonna spend too much more writing about it. I’m sure each film felt “experimental” to its creator, but there was nothing here we hadn’t seen before. Also with few exceptions people feel the need to accompany their “experimental” images with “abstract” blippy swimmy music, ugh. Also also, forget any references to “film” below, since everything but Shake Off was on video (and Shake Off either originated on HD or at least had mostly digital components). Why can’t everyone call ’em “movies” like I do? All quotes are from the film festival booklet, with their queer use of commas intact.

Doxology (Michael Langan)

“An experimental comedy…” Cute. Tennis balls and automobiles and vegetables defy space and time – funny and not overlong. Probably would’ve been my favorite here, but the picture was fucked and distorted, stretched out much wider than it should have been. Thanks, AFF365/Landmark.

Such As It Is (Walter Ungerer)

“The film is divided into four parts and four themes: the underground in the city; above ground in the city; a field in the country; and fog and the ocean. Each theme has its separate identity, yet they are not separate. Through manipulation and abstraction of imagery the four parts are joined, as the land, and the air, and the oceans are joined by the earth.” Besides the over-use of commas at the end there, this description is far better than the film it describes. The interminable subway bit, tiny flicks of reflected light turned into digital noise on an ugly gray glowing background, seemed suddenly less crappy in comparison when I saw a cityscape turned into spinning 3D cubes within cubes. What did they mean by the title? How is it? This was the first of a bunch of ugly video-projected shorts (from digibeta or dvd?). I do a bit of quality-control on our video deliveries at work, and I never would’ve allowed this thing to go out with all the banding issues it had. Go check your After Effects settings, re-render in 16-bit and bring it back to me later.

A Convolution of Imagined Histories (Micah Stansell)

“The film is comprised of four chapters, telling four separate stories that make up a meta-narrative. The works are the result of imagining the visual track to the story of someone else’s memories.” One of those short films where a narrator talks about shit their parents did when they were young or before they were born, like The Moon and the Son but with less animation and more overlapping sounds and video and slow/fast effects… anything to make it seem interesting (which it was, but only barely). Director in attendance seemed a nice enough guy. Talks not about “filmmaking” but “compositing”. Experimental Short Composites would be a more honest name for the program.

Dear Bill Gates (Sarah J. Christman)

“A poetic visual essay exploring the ownership of our visual history and culture.” Thought I was in trouble when the voiceover said “40,000 years ago…” but it was well-done, with deep storage of photos in old mines subliminally connected with “data-mining” and the mining of our memories. The longest of the shorts, and interesting enough to justify its runtime.

Passage (Peter Byrne)

“A reflection on the peripheral… this work visually catches sight of experience, as it moves past.” Notes I took in the theater read: “flickering, fluttering digital colored mess overlapped w/ blurry video of birds w/ sucky jangly music. These all have crappy music. I can hear yawning.” Film festival directors: I am available to write blurbs for your shorts programs!

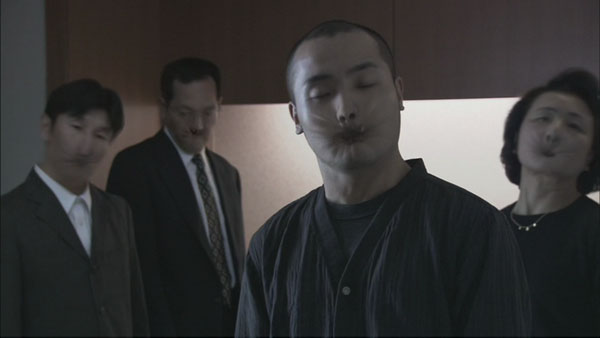

Office Mobius (Seung Hyung Lee)

“An abstract story…” I didn’t find it abstract at all. Kinda cute buncha office collisions, with one character who got laughter whenever he’s on screen – a star in the making. My notes say “butt-ugly digi credit titles.” Letterboxed within the 1.33:1 projector frame within the 1.85 movie screen.

24 Frames Per Day (Sonali Gulati)

“The film raises important questions around immigration, cultural stereotypes, and the meaning of home from a transnational perspective.” Bunch of field recordings interspersed with a fake-sounding conversation (perhaps based on a real one) between director and “cab driver”. The stop-motion visuals of a hallway manage to be less interesting than the soundtrack. They say it was shot 24fpd over nine months, but La Region Centrale (or even 37/78 Tree Again) this ain’t.

Drop (Bryan Leister)

“The aesthetic journey of a drop of water – animation sound and image are combined to create a zen-like exploration of fluidity and nature.” I might have written: “a bit of nothing to fill out four minutes in the program.” Nice to hear actual music, though.

Rewind (Atul Taishete)

“The film moves in reverse towards the beginning as the opening of the film evolves as the climax.” Clumsily worded, but what they mean is the film’s shot totally in reverse, not just in reverse-ordered segments like Memento. Unlike Memento, there’s no reason within the narrative to justify the reversal, except I suppose that it wouldn’t have been as cool (or “experimental”) in regular motion. It’s about a blind guy in a diamond heist and ahhh, I’m not going into it. This also had music.

Shake Off (Hans Beenhakker)

“A perspiring boy dances magically across borders.” Seriously, a perspiring boy? I would’ve called him a “dancer” as do the credits, but then they would’ve had to think of a synonym for “dances” as an action verb. Can’t tell if it was the same dance footage looped four times, or just a similar performance. The dance and fluid camera movements weren’t enough – they had to put fakey digital backdrops behind the guy and with David Fincher zooms and cuts that appear seamless. A nice dance & technology demo.

The last two (both non-U.S.) are the only ones listed on IMDB. I spend so much time on that site, sometimes I consider making a film JUST so I can be listed on IMDB. These compositors have different ambitions than I do.

Sometimes I consider taking this “blog” off the internet and making it for my eyes only. I just know one of the filmmakers is going to google themselves, find this page and be offended. I’m sorry!